Trouble in Toyland 2023

Threats stem from toys with microphones, cameras and trackers, as well as recalled toys, water beads, counterfeits and Meta Quest VR headsets

VIEW THE FULL TOYLAND REPORT

Last month, an 11-year-old girl was kidnapped by a man she encountered while playing a game online. Fortunately, she was found safe a short time later, about 135 miles away from her home. The game, Roblox, is one of the most popular mobile games this year.

This past spring, the Federal Trade Commission accused Amazon of violating the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act Rule (COPPA) through its Alexa service by keeping the voice recordings of children indefinitely and failing to delete childrens’ transcripts, even when a parent requested they be deleted. Amazon also gathered geolocation data and used childrens’ transcripts for its own purposes.

A few years ago, Fisher Price’s Smart Toy Bear was discontinued. It was created for children ages 3 through 8 as “an interactive learning friend that talks, listens, and ‘remembers’ what your child says and even responds when spoken to,” according to WeLiveSecurity. But research found a security flaw in the app would allow hackers to get information about children without permission.

This toy bear is not an isolated case. Multiple toys from major manufacturers have been discontinued in recent years after research from various groups showed that children’s voices, images, locations and other information was being improperly collected or hacked. In other cases, vulnerable toys are still for sale.

These days, we’re surrounded by smart devices – all of these things with microphones, cameras, connectivity, location trackers and more. These devices connect to the internet and/or to the outside world, and they gather and store data, sometimes very poorly. Our children’s holiday gift wish lists may be filled with stuffed animals that listen and talk, devices that learn their habits, games with online accounts, smart speakers and watches, or all kinds of toys that require you to download an app.

The global market for smart toys grew from $14.1 billion in 2022 to $16.7 billion this year, according to a large market research firm. The business of smart toys is expected to more than double by 2027.

These toys, and the threats that come with some of them may increase with the incredible growth of artificial intelligence. AI is now advertised in toy robots, games and interactive toy animals, some aimed at children as young as 3 years old. AI-enabled toys with a camera or microphone may be able to, for example, assess a child’s reactions using facial expressions or voice inflection. This may allow the toy to try and form a relationship with the child and gather and share information with others that could risk the child’s safety or privacy.

For Trouble in Toyland 2023, our 38th annual toy safety report, we are focusing first on smart toys and what parents and gift givers need to know to protect the children in their lives.

We also are looking at:

-

Water beads, which are often used as sensory toys, but the tiny, squishy balls can be deadly.

-

The ongoing risk posed by online retailers that continue to sell recalled toys in violation of the federal law.

-

Ongoing threats from high-powered magnets, button batteries, choking hazards, counterfeit toys and inadequate warning labels.

Toy safety tips for families and gift-givers

In recent years, traditional toys such as stuffed animals, games, race tracks and building sets have become safer overall. That’s largely because of tougher laws adopted in 2008, good oversight by regulators, efforts by many manufacturers, watchdog work by consumer advocates including PIRG and more awareness by parents and caregivers.

Some of the biggest threats in recent years are coming from different sources, such as counterfeit toys, fidget toys that violate safety standards, recalled toys still for sale and toys that invade children’s privacy.

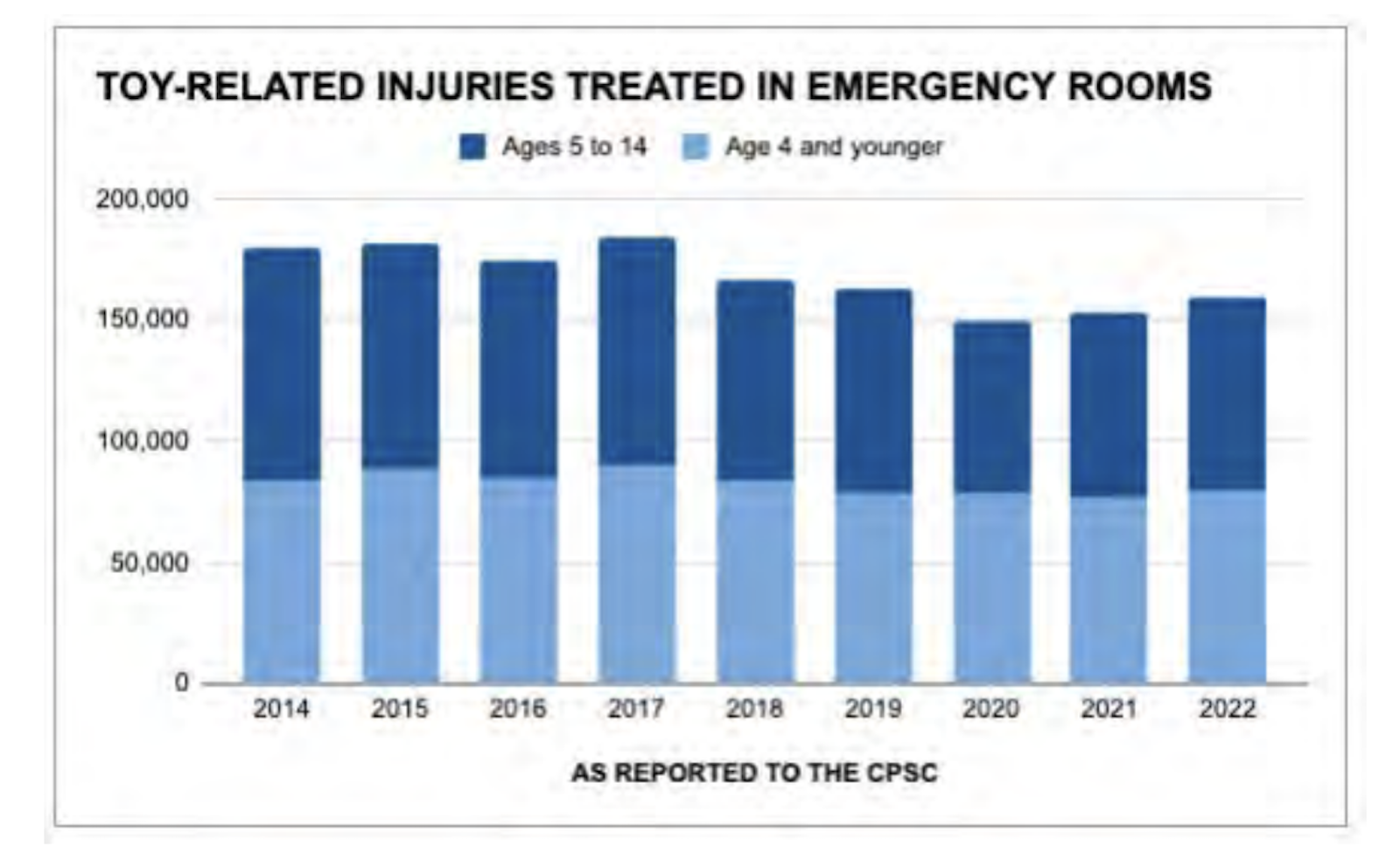

Toy-related deaths and injuries treated in emergency rooms among children 14 and younger have declined over the years, but there are still more than 150,000 such injuries a year. This of course doesn’t include injuries treated in doctors’ offices or that don’t require medical attention. Not all injuries are caused by dangerous toys; sometimes an incident is caused by misuse.

PIRG also tested both Meta’s newest virtual reality (VR) headset — the Quest 3 — and Meta’s new junior VR accounts aimed at children ages 10 to 12. These wearable console systems create a 360-degree computer-generated world. We found using Meta’s new junior accounts greatly increases parental controls over a child’s VR experience – but we also found these new additions fail to eliminate some real concerns. Other researchers have found that even for teen Quest headset users, there are plenty of serious risks.

VR risks for kids and teens

We’ve identified six main reasons parents should approach VR and Meta Quest headsets with caution:

1. The technology is in its very early days.

We talked to pediatricians who strongly recommend waiting for Meta to do more thorough testing to ensure VR is safe, and for other research on the effects on kids’ and teens’ developing brains before getting one. “It’s just not worth the risk right now,” developmental pediatrician Dr. Mark Bertin said in an interview with PIRG.

2. The physical Quest headset is not designed to fit still-developing young bodies.

According to Meta, your child could end up with minor injuries, or possibly problems with visual development.

3. VR feels really real.

It feels so real it’s even being used to do virtual exposure therapy for phobias. But as child clinical psychologist Dr. Brett Kennedy pointed out, “If it feels that real, how you use it really matters.” Even mild violence is a lot more intense in 3-D. VR content can also have a bigger impact on users’ bodily reactions and mood than 2-D games, especially for younger users, and those effects can last long after you’ve taken the headset off.

4. Many of the most popular games and apps available emphasize social interactions with others online, which can turn negative pretty quickly.

In PIRG’s testing, we found interactions with our test 10-year-old’s junior account ranged from bizarre to disturbing, including another player shooting himself in the head in front of our young player in an app rated OK for 10-year-old children. Other researchers using teen accounts on popular apps have experienced sexual harassment and even sexual assault attempts, particularly when using teen girl accounts.

5. Some of the most popular apps available for use with Quest headsets include sexually graphic content.

This includes lewd audio group chats and people using their virtual avatars to simulate sex. Researchers have found minors have ready access to this content thanks to loopholes, poor moderation controls and content labeling failures.

6. Quest headsets can gather a lot of data about users.

Playing games often requires agreeing to different third-party companies’ data practices wholesale. VR headsets can also gather sensitive motion data, which can be used to infer health or demographic details about you, and there’s virtually no regulation controlling how companies or other actors use this data.

The experts we spoke to recommend parents approach VR using the precautionary principle – don’t use it at all until these problems have far better solutions, and Meta proves we can trust it with our children and teens.

If you are thinking of going ahead and getting a Meta Quest VR headset for your child or teen, we walk through the things to think about.

THE SMART TOY CRAZE

The range of smart toys on the market is growing. Toys we never thought needed to be smart suddenly are: Besides toy robots that follow commands and stuffed animals that talk to us, we now have miniature soccer balls that require an app, toy cars with sensors to respond to hand motions, and tablet-interactive doctor’s kits that make “playing doctor” a digital affair. Many of the major toy manufacturers have begun to offer more high-tech toys, including Hasbro, Mattel, and Lego.

Smart toys can incorporate various technologies, like cameras, microphones and sensors, as well as artificial intelligence capabilities and connectivity through the internet or Bluetooth.

Connected smart toys are also considered a part of the Internet of Toys (IoToys), featuring a range of Wi-Fi or Bluetooth connections, including remote-controlled drones, smartwatches and app-connected action figures. Some can collect data on your child and transmit it off of the toy to a company’s external servers. For example, some interactive dolls with conversation capabilities use microphones and Wi-Fi to transmit a child’s words to speech recognition software maintained by the company. The software then compares the child’s words to a database of possible responses, which the company then transmits to the doll’s microphone over Wi-Fi.

Parents may find that smart toys have their benefits. Companies often say that making a toy “smart” will keep children engaged longer by enabling new play features through software updates.

But smart toys come with unique risks that parents should be aware of.

Read more

An uncomfortable reality of smart toys: We don’t know with certainty when our child plays with a connected toy that the company isn’t recording us or collecting our data. All we have is their promise and the threat of consequences if they break it.

“A company is required by law to abide by claims about its privacy practices stated in its privacy policy and in other representations,” Samuel Levine, director of the Bureau of Consumer Protection at the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), told U.S. PIRG Education Fund. “If the toy is directed to children under 13 years old, the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act, or COPPA, requires the toy company to ask for your consent before it collects your child’s personal information.”

But there’s a long list of companies the FTC has sanctioned, saying they violated COPPA. In these cases, consumers found out only after the fact.

Recent FTC violations include:

Microsoft, 2023. Will pay $20 million to settle allegations that it collected children’s information on its Xbox gaming system including their full name, phone number, email address and date of birth without parental consent. As part of the action, the FTC also made it clear to Microsoft and other companies that a child’s personal information includes health information, vital signs and biometric data such as eye tracking, iris and retina scans, voiceprints, fingerprints, and hand and face geometry.

Edmodo, 2023. Ordered to pay $6 million but it was suspended because of the company’s inability to pay. This was an educational product aimed at students, not a toy, but the company was accused of using children’s data for advertising purposes.

Google and YouTube, 2019. Paid $170 million to settle allegations that Google’s YouTube video sharing service illegally collected personal information from children without parental consent.

VTech, 2018. Paid $650,000 to settle allegations that its Kids Connect app, used with various Vtech toys, “collected the personal information of hundreds of thousands of children” without notice or consent from parents as required under COPPA. This was the FTC’s first children’s privacy case involving a toy that connects to the internet.

And the previously mentioned case involving Amazon, 2023. The FTC and DOJ charged Amazon with violating children’s privacy laws by using its Alexa/Echo service to obtain and keep children’s voice recordings and geolocation data for years, and then deceiving parents who requested data be deleted and using the data for its own purposes. The government proposed ordering Amazon to pay $25 million for its COPPA violation.

It’s notable that Amazon also offers Alexa-enabled devices and toys, such as a play kitchen and a board game currently. It’s removed at least one toy’s Alexa functionality by taking down the software that once connected the Fuzzible Friends stuffed animals to Alexa and Echo. We may see a growing number of toys in the future that connect to Alexa.

Internet- and bluetooth-connected toys come with particular risks

Connected toys that access the internet can often collect and store personal data, including audio recordings and user preferences. Collecting this type of data can make your or your child’s information more vulnerable to hacking or unauthorized access, as was alleged with Hello Barbie and CloudPets. Data breaches involving various toys and unencrypted data from child users have already been reported.

Additionally, some connected toys can access internet content, which can expose children to inappropriate or harmful material without proper filtering and parental controls. Parents may want to weigh any possible educational benefits of devices with internet access against the risk of children unknowingly accessing inappropriate photos or websites.

While regulators and lawmakers have focused on the safety and privacy of children online for a quarter-century, it’s an evolving issue as we see new technology and better technology every year. Levine of the FTC notes the agency has focused on children’s privacy online since supporting COPPA in 1998.

It’s good for parents to know that regulators are monitoring the landscape for companies that violate the law and put our children at risk. We likely will see more enforcement and further regulation in the future.

“The FTC is staying on top of trends in the marketplace, like the emergence of artificial intelligence, virtual reality and augmented reality, and their potential implications for children’s online privacy,” Levine said. “Congress is also considering legislation that would strengthen privacy protections for children.”

In the meantime, parents and gift-givers can assess a toy they may be considering, or a toy their child already has using our tips below.

SMART TOYS HELP FOR PARENTS & GIFT-GIVERS

We offer insights on smart toys in three ways:

- The types of technology that raise issues and questions you should ask.

- A look at some good and bad toys.

- What to know about specific types of smart toys or children’s gifts.

All smart toys may pose a risk to children, depending on the specific toy, the age of the child, the child’s technical skills and their capacity to understand what’s OK and what’s not.

Up front you can ask your friends and family who might be shopping for your child not to buy a smart toy without checking with you first. Likewise, don’t buy a smart toy for a child in your life without checking with their parent or guardian.

For any gifts you are considering, you can do a web search for the toy and read reviews people have written. Do any of them cause you concern? Also, look up the toy manufacturer. Does it have a history of troubling violations? What does the toy’s privacy policy (which should be available online) say about what the toy does and information it collects?

“Parents and caregivers should understand the toy’s features,” said Samuel Levine, director of the Bureau of Consumer Protection at the Federal Trade Commission (FTC.) The big questions parents should pursue, he said:

- Does the toy allow the child to connect to the internet and send emails or connect to social media?

- Does it have a microphone or camera? If so, when will it record, and will you know it’s recording?

The specific questions you should ask vary based on the type of toy and its features. In many cases, you should be able to find the information in the toy’s privacy policy, which you can find online. (Make sure you’re looking at the policy for that toy, not the company in general or just its website.) The answers may help you decide whether the toy is appropriate to buy for your child, what controls you can put in place or whether you should return the toy.

In some cases, you may not discover whether you’re comfortable with how the toy operates until you actually use it. If you’re not satisfied, you can return it.

QUESTIONS FOR PARENTS TO ASK ABOUT SMART TOYS

If it has a microphone:

- Is the toy’s microphone always on? Does it have a wake word? (This can mean it’s always listening.) Or is there a button you have to hold down in order to activate the microphone? The latter option is the safest feature.

- Is there a light or some indication the microphone is listening?

- Does it have a secure Wi-Fi or Bluetooth connection, which would prevent a stranger from talking to or listening to your child through the toy? For example, does it require you to set up your own strong password before play? Or does it allow you to use the toy with a weak default password that could be easily guessed – which could put your kid in danger?

- Do the recordings get collected by someone or some company using a Wi-Fi or Bluetooth connection?

- Where is the collected information stored – just on the toy, or also on the toy company’s back-end server, or that of a third party “service provider”? The more companies store your child’s data on their servers, the more likely it will be exposed in a breach or a hack.

- How are the recordings used? Some companies say they use recordings to improve their products. Others share them with third parties. In both examples, children and their families could be at higher risk of fraud, unwanted advertising and identity theft.

- Does the privacy policy specifically mention security being a priority for data it collects? Are the recordings stored securely? If not, then you may be better off finding a toy company that takes your child’s safety and security more seriously.

- How long are the recordings retained? If the company fails to delete the data beyond what’s necessary to fulfill the play function, it can increase the odds your child’s data will eventually be exposed in a breach or a hack.

- Who has access to the recordings, or who are they shared with?

- Can you review recordings of your child and tell the company to delete the ones you may be uncomfortable with? This is useful particularly in the case of a child sharing more personal information with a conversational toy than you’re comfortable with.

If it has a camera:

- Are the photos your child takes stored on an SD card or sent through Wi-Fi or Bluetooth? Storage on an SD card allows you to review and better control what happens with the photos. Sending photos via W-iFi or Bluetooth is faster but can represent a risk of photos getting in the wrong hands.

- If they can be sent, are the photos stored on the toy company’s back-end server?

- Does the privacy policy specifically mention the security it uses for images or photos it collects?

- Who has access to the images or photos or who are they shared with? Does the company’s privacy policy say it shares with third parties?

- Can you access images or photos the company stored or shared??

- What does the company’s privacy policy say about your ability to require the company to delete images or photos?

If it connects to Wi-Fi:

- Does it connect automatically to unsecured Wi-Fi networks? A toy for a child should not. You want a button on the toy that must be pressed or some intentional action you take to allow it to search for a network. If there’s not a button, is there at least an app that requires a password to connect to Wi-Fi?

- If the toy connects to an unsecured Wi-Fi network, is it able to block any intrusions? You likely have to test this.

- Does it provide a way for your child to send or receive messages, or connect to any social media accounts? The privacy policy might indicate this. Or you might discover it when setting up the toy. It might recommend you to sign in via Instagram or Facebook, for example, or send messages to invite “friends” to connect to your child, and their toy. You don’t want to connect a toy to a social media account.

- Does it share any information about your child, including geolocation? If so, it should be clear in the privacy policy, and you want to approach with caution whenever a toy gathers data as sensitive as your child’s whereabouts.

If it connects to Bluetooth:

- Is the Bluetooth connection secure with a strong password? Or when you set it up, does it pair automatically with a device that’s close, without a password? This could be dangerous if the toy has a range outside your home, or if the child takes the toy to public places.

- Does it contain a GPS that can be tracked, as many smartwatches have? This should be stated in the privacy policy. Location tracking could put your child at risk if the Bluetooth connection isn’t secure. Good smartwatches and other secure products will allow you to block unauthorized pairing or require two-factor authentication.

If it collects any personal information from your child or about your child, and that child is under 13 years old:

- Does it transparently and clearly ask for permission to collect data from your child before your child begins play? Companies are required to do this by law. The privacy policy should state its practices. But if your permission isn’t required when setting up the toy, you should return the product and report the company to the FTC online or by calling (877) FTC-HELP. If you need one-on-one help, the FTC says you should contact your state attorney general.

- Does the toy state in its privacy policy that it is a product meant for children to use, or does it say, “This product is not intended for use by anyone under 13?” If it’s the latter, stay away. It will gather data about your child as if they were an adult, even if they are under 13.

- When you’re setting up the toy and receive the notification asking for your consent, does it contain a link to the service’s privacy policy, as it must by law? If it doesn’t, that’s a flag.

- Does it tell you how the information it collects is secured and note that you have the right to get your child’s information deleted? These are required by law. If it doesn’t provide these disclosures, you should return the product and report the company to the FTC online or by calling (877) FTC-HELP. If you need one-on-one help, the FTC says you should contact your state attorney general.

If it collects data on anyone of any age:

- Can you find its privacy policy? If not, stay away. Reading the privacy policy is where you’ll find the answer to some of these questions:

- What types of data does it collect? Photos? Recordings? Your location? You need to decide what you feel comfortable with. You may be OK with a device knowing your location, but not recording conversations. If the privacy policy isn’t acceptable, you shouldn’t buy the product. If you already have it, you should return it.

- Does the privacy policy say any information collected gets stored on a back-end server? The more information that’s stored, the more that can get into the hands of a bad guy if there’s a breach or hack.

- Does the privacy policy specifically mention security being a priority for the data it collects? Does it tell you that it stores data securely? If not, you may want to find a product from a company that takes your family’s safety and security more seriously.

- How is the information shared and who has access to it? Does it share with or sell data to third parties? This puts you at higher risk of fraud, unwanted advertising and identity theft.

- What are the default data collection settings? Especially pay attention to settings like collecting your geolocation automatically.

- How difficult is it to find settings on the product or app that restricts features you don’t want to be active? If it’s too cumbersome, you may want to return the product.

- Does it push advertising, particularly based on personal information collected? Its privacy policy should say whether the company or a partner uses data for marketing purposes. If you don’t want more marketing calls, texts or emails, you should opt out of having your data, including your contact information, used for marketing.

If there’s a privacy policy:

- Does it make it easy for you to find information related to children’s data, like pulling the section on children’s privacy to the top of the document? If it doesn’t make it easy, this is a flag.

- Does it say the product isn’t intended for users under 13? That means it’s probably gathering a lot of data about your child because if it were for children under 13, the law requires greater data protections.

- Can you find and easily understand the information you need to decide whether you can control what personal data is shared and with who? If not, you shouldn’t buy the product. If you already have it, return it.

- Does the company indicate it can “update” its privacy policy? Does it indicate how you will be notified if it does update or change anything? You should have the option to sign up for an email notice, instead of needing to remember to check the company’s website periodically to find out.

If it has an app:

- What information does it require to create an account? You should not allow a young child to create an account without your oversight or with an email account you can’t access.

- Does the app developer have a privacy policy you can easily locate?

- Does the app’s privacy policy state that its services are not intended for children under 13? If this is the case, it’s very likely going to collect data on your child regardless of their age.

- What data does the app collect, according to its privacy policy? What is it used for? In your device settings, you should be able to opt out of data sharing you don’t want, such as your location or browsing history.

- Does the app include in-app purchases? You may want to look into parental controls on spending so your child doesn’t inadvertently wrack up big bills you don’t want to pay.

- How secure is the app? Does it have social features, allowing unwelcomed messages or allowing strangers to communicate with your child? You do not want to connect it to or sign in with social media. If you don’t and your child is getting unwanted messages, you may want to look at the settings again and delete the app if the problem persists.

If it allows your child to spend money:

Substandard practices can lead to your child spending too much money without your permission or buying things you don’t approve of.

- Is there a monthly subscription that costs more than you want to pay?

- Does it store payment information or link to an iTunes, Amazon, PayPal or other account, or save your credit card on file? This could make it easier for your child to spend money without your authorization.

- Does the account or app have parental controls you find useful to limit or monitor spending? This can include requiring your approval for each transaction or for transactions above a certain dollar amount. You may also be able to set alerts to better monitor your child’s spending.

- Does it require a balance to be kept in the account? This may allow purchases without your permission.

- What’s the process for challenging a transaction?

- What’s the highest dollar amount for a single item? Apps can include purchases ranging from 99 cents to $99.99. If high-priced items are easily purchased, it may be more important to you to find and set those parental spending controls.

A LOOK AT THE GOOD AND THE BAD

We bought a few smart toys to see how they work, whether they do what they say and how easy it is to protect information. This isn’t a full review or absolute recommendation for or against buying any of them; it’s just meant to be a look at how some real toys work and the issues you might encounter.

A TOY WITH UNSECURE BLUETOOTH

Amazmic Kids Karaoke Microphone

This $15 toy karaoke microphone “uses the latest Bluetooth 5.0 technology to provide a more stable connection” – up to 33 feet, according to the online listing. It promised fast pairing and said it’s compatible to pair with a phone, tablet, laptop, etc. It also is compatible with a TransFlash card and cable connection.

The instructions say the device requires a password to pair. Good. But the password is 0000. Not good. Further, our microphone paired in about two seconds – with no password at all. We tried this three times on three different iPhones. Same unsecure result with no password required. We were able to pair at about 30 feet. It’s troubling there doesn’t appear to be an easy way to make it undiscoverable so strangers can’t drop in on your child and send undesirable audio messages or play inappropriate music. It does have all kinds of pretty lights. And when you play music through the speaker, it has great sound, to be honest.

A TOY WITH A SECURE BLUETOOTH

VTech Kidi Star DJ Mixer

This does require a PIN, which the company encourages users to keep enabled: “VTech strongly recommends keeping the PIN security on for the use of Bluetooth transmission to avoid any connection by an unauthorized device. The disabling of the PIN security should only be used when the connection of an external device with PIN security is impossible. The use of the toy when PIN security has been disabled should be under the supervision of an adult.”

In addition, if a device tries to connect via Bluetooth, the toy requires giving it permission. The pairing process requires pressing the Bluetooth connect button to search for a nearby device. Once the device is paired, you have to press the Bluetooth input button to allow this as the audio source. It sells for about $54.

TWO TOYS WITHOUT THE ABILITY TO CONNECT THROUGH WI-FI OR BLUETOOTH

Prysyedawn Toy Smart Phone

This toy smart phone does not connect through Wi-Fi or an app. You can take photos, listen to music and play games. It also has other features such as an alarm clock and calculator. Photos are stored on an SD card. You have to connect it through a USB cord to download photos. This gives the user more control over their child’s data. This sold on Amazon for about $33.

Goopow Kids Camera-Video Camera for 3-8 Year Olds

This children’s camera takes photos and shoots video. It does not connect through Wi-Fi or an app. It says it can take up to 1440x1080P video and has other functions, including choosing different scenes. Photos and videos can be downloaded through an included card reader. This gives the user control. This is an Amazon “best-seller,” available for about $31.

A TOY WITH A BAD PRIVACY POLICY

Cognitoys Dino

This cloud-based, Wi-Fi-enabled smart dinosaur was introduced in 2016, aimed at 5- to 9-year-old children. The dinosaur engaged in conversations, told jokes and stories and answered questions. Connected through W-iFi and powered by IBM/Watson, it was intended to be a toy “that learns and grows with children.”

Dino didn’t last long as the tech company behind the toy folded and the app support was discontinued. The privacy policy was disturbing. Here’s a small sample:

“Information We Collect

“Personal Information. We collect information that possibly personally identifies you and your child, such as your full name, address, mobile phone number, wi-fi SSID, IP address, device MAC addresses, e-mail, payment information (including zip code), child’s name, child’s date of birth, child’s gender, and other personally identifiable information, that you choose to provide us with or that you choose to include in your account (“Personal Information”). For example, you may provide us with certain Personal Information when you use the Parent Panel. The “Parent Panel” is the interface available on the Site and through the Offerings, that allows parents to view Play Data (defined below) and to manage Dino settings.”

“Play Data. When a child interacts with his or her Dino, we automatically collect certain play-related information from your child and from such interactions (“Play Data”). For example, when your child plays with the Dino, we may automatically collect information about your child’s likes and dislikes, interests, and other educational metrics.”

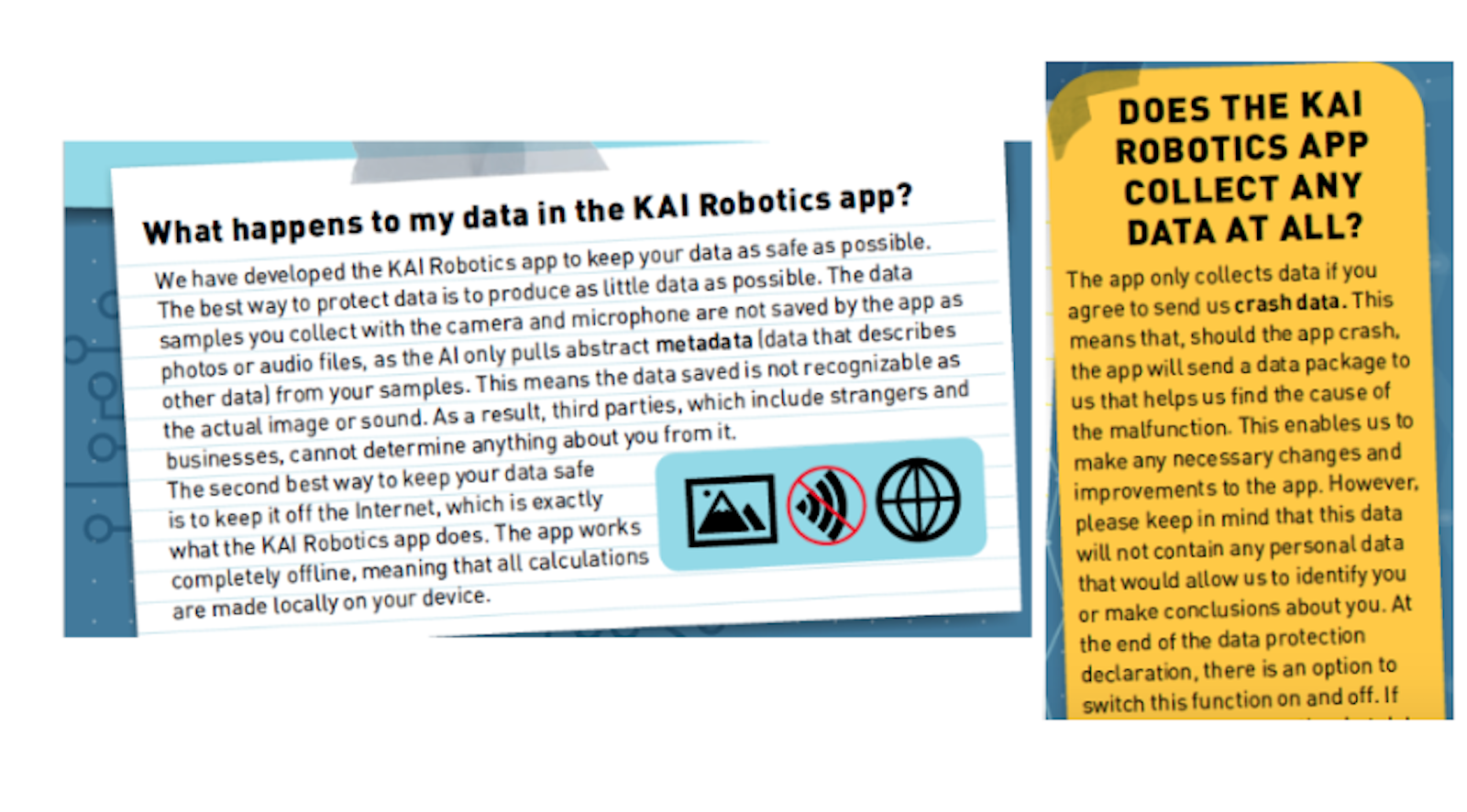

A TOY WITH A GOOD PRIVACY POLICY

KAI: The Artificial Intelligence Robot

The Kosmos Artificial Intelligence robot allows users to “explore the concept of machine learning” by building and programming an intelligent, six-legged, app-enabled robot that is supposed to respond to sounds and gestures.

This toy’s privacy policy is an example of a good, easy-to-read explainer. It spans two pages of the toy’s 68-page instruction manual. A couple of excerpts below.

WHAT TO KNOW ABOUT SPECIFIC TYPES OF SMART TOYS

DRONES

The last few years have seen a surge in consumer drones thanks to better technology, lower prices, increasingly user-friendly controls and opportunities for aerial photography and recreational use. As the technology continues to advance, the consumer drone industry is expected to continue to grow. An expanding market for retailers is marketing drones to children.

Drones for children can vary greatly in price, capabilities and intended use, from indoor toys for preschoolers, to camera drones, racing drones and stunt drones. They can cost as little as $30 or can top $10,000.

Drones come with a unique set of concerns:

- Safety first: Drones with fast-spinning propellers can be dangerous. Collisions with people, animals or property can lead to injuries or property damage. A toddler in the UK lost an eye after being hit by a drone flown by a family friend.

- Legal responsibilities: Drones come with unique legal responsibilities. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) oversees drone rules but states and localities may place additional restrictions. The FAA requires all drones that weigh greater than 0.55 lbs (250 grams) to be registered.

- Respecting privacy: Drones equipped with cameras can intrude on others’ privacy, leading to unintentional privacy violations, which children might not fully grasp.

ROBLOX

Roblox is one of the most popular mobile games among kids this year, cracking the top 10 in downloads for both Android and Apple. Roblox offers a creative and engaging platform for kids to design games, interact with friends and unleash their creativity, but it’s not without its potential dangers.

Inappropriate content: Roblox allows users to create and share content, leading to potentially age-inappropriate games and avatars. Instances of explicit or violent themes have been reported in Roblox games. User-made avatars can introduce children to inappropriate content.

- Online predators: An 11-year-old girl from Delaware was kidnapped from her home by an adult who communicated to her through Roblox. She was later found safe.

- In-app purchases and microtransactions: Roblox makes its money through in-app purchases and its artificial currency Robux. Kids may not grasp the consequences of real money spent on virtual items and spend more than parents would prefer.

- Addictive nature: In 2020, 36 million people — two-thirds of them under 16 — spent more than 30 billion hours on Roblox. Its engaging gameplay can lead to excessive screen time, raising concerns with some experts about the game fostering Internet Gaming Disorder among young users.

SMART SPEAKERS

Smart speakers are among the most popular Internet of Things (IoT) devices in American households. These voice-activated virtual assistants, such as Amazon Echo, Google Home and Apple HomePod, have found their way into millions of homes, offering various capabilities such as streaming music, sending messages, controlling other smart devices and conducting web searches.

With more than 71 million Alexa-enabled devices in use as of 2023, these smart speakers have quickly become ubiquitous. However, the rise of conversational commercial products also raise significant privacy and safety concerns for both adults and children:

- Data collection: One of the primary issues with smart speakers is their persistent data collection. Equipped with internal microphones, these devices wait for a specific “wake word,” often the name of the virtual assistant persona created by the respective company, such as Amazon’s Alexa, Apple’s Siri, or Microsoft’s Cortana, to activate. While this system is designed to be convenient to consumers, it’s not without flaws.A 2020 study by Northwestern University researchers found that Apple, Microsoft, Google and Amazon smart speakers were prone to accidental activations, recording users’ conversations without a “wake word” prompt up to 19 times a day. In 2023, Amazon paid $25 million to settle FTC and DOJ allegations it had violated COPPA for failing to delete young users’ voice and geolocation data collected by its smart speakers.

- Inappropriate content: Smart speakers can access content from the internet, which means children may encounter or request inappropriate content, such as explicit music, jokes or harmful advice. While these devices aim to filter profanity, third-party apps can contain content that parents may not want their children to access. In one case, academic researchers were successfully able to smuggle 234 policy-violating skills onto the Alexa Skills Store, the marketplace for third-party apps on the Echo smart speaker.

- Voice-enabled online shopping: Smart speakers offer voice-activated online shopping, and children left unsupervised may make unauthorized purchases. This can result in high charges on a parent’s credit card, as was the case with Brooke Neitzel, a 6-year-old who unwittingly spent $160 of her mother’s money on a KidKraft Sparkle Mansion dollhouse and dozens of sugar cookies. Neitzel made the purchases by simply asking her Amazon Echo device “Can you play dollhouse with me and get me a dollhouse?”

SMARTWATCHES

Smartwatches can be a fun and functional wearable technology. They may provide entertainment for kids and peace of mind for parents hoping to have a way to communicate with their child before making the jump to buying a smartphone.

There are hundreds of kids’ smart watches on the market with varying degrees of technical capabilities and at various price points. Some are very basic with low-fidelity LCD displays that allow kids to see the time and play some mobile games. They typically sell for less than $40. On the other end of the spectrum, there are watches such as Verizon’s Gizmo Watch 3, a 4G-enabled kids’ smart watch that acts as a communication device through its app with connected-GPS tracking and video calling capacities. The 8GB Gizmo Watch 3 sells for about $150.

Smartwatches come with some security and privacy considerations for parents and guardians.

- Location tracking risks: While location tracking is a key safety feature, it can inadvertently expose a child’s whereabouts and pose risks if data falls into the wrong hands. The Norwegian Consumer Council found multiple critical security flaws in various smartwatch brands that could expose real-time location data, and could be made by hackers to display an incorrect location — alarming if a child’s location was needed in an emergency.

- Data privacy vulnerabilities: Some smartwatch companies share technical backend infrastructure, meaning vulnerabilities in one smartwatch can affect others. A study of children’s smartwatches in 2020 found that several lacked encryption and authentication, potentially exposing childrens’ sensitive data.

Smartwatch companies have come under fire by European regulators, with kids’ smartwatches that can eavesdrop without being detected being banned within Germany. The German telecoms regulator, the Federal Network Agency (BNetzA), went as far as recommending that parents destroy these “eavesdropping” devices.

THE DANGERS OF WATER BEADS

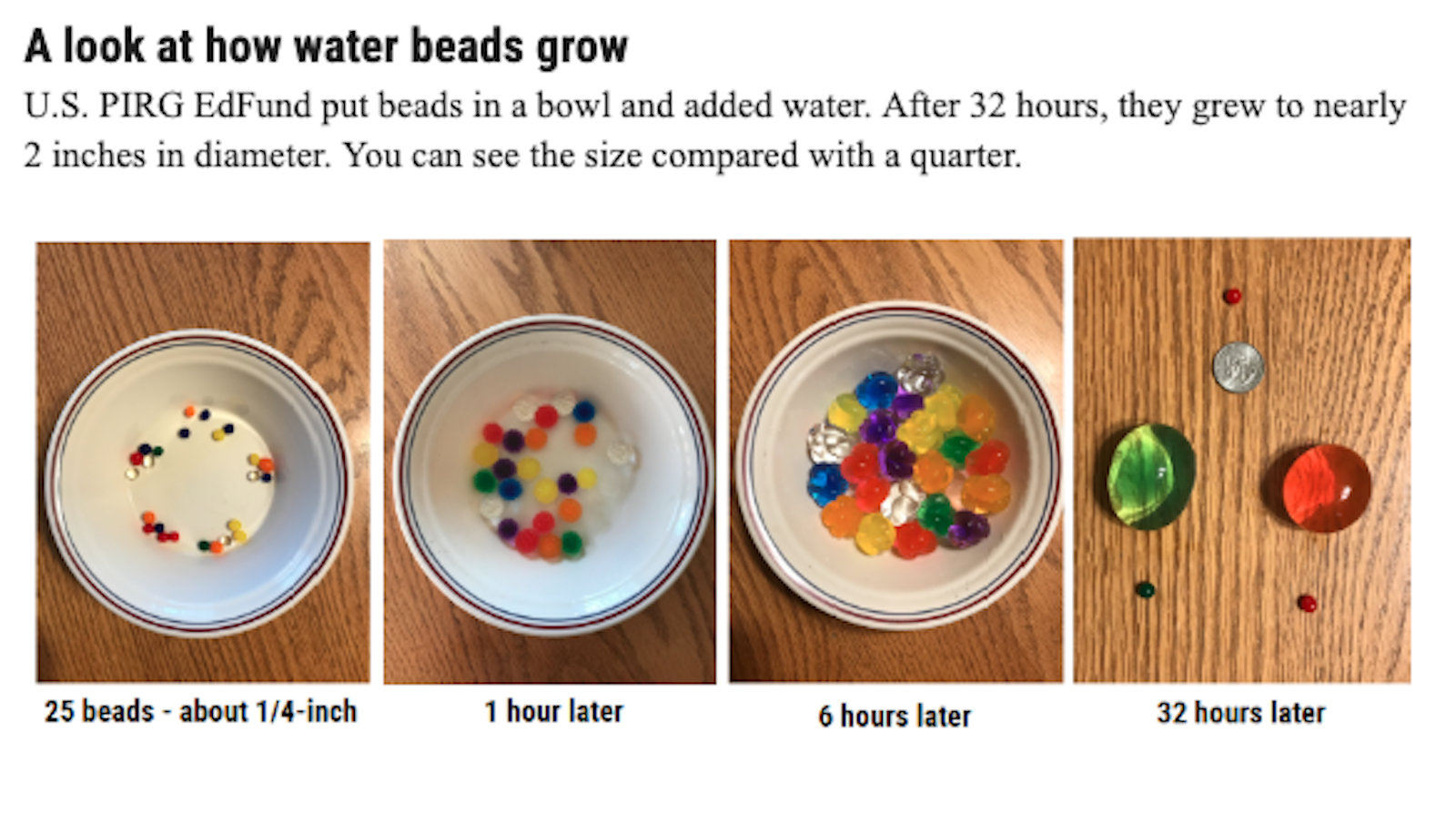

Water beads are a colorful, squishy sensory toy. Some are small as pinheads or ice cream sprinkles. Some are the size of marbles. The problem is, as the name suggests, something happens when combined with water. What they do is grow, from the size of a pea, for example, to two inches in diameter.

So if a child swallows one of these beads that are colorful and look like candy, it can expand in the child’s body. It can block the airway or damage the digestive tract.

“If ingested, inhaled, or inserted in ear canals, water beads absorb bodily fluids and can lead to potentially life-threatening injuries,” said Dev Gowda, deputy director of Kids In Danger in Chicago. Those can include intestinal or bowel blockage, lung or ear damage and other life-altering injuries.

About 7,800 children were treated in emergency rooms from 2016 through 2022 for injuries or illnesses caused by water beads, according to data from the Consumer Product Safety Commission.

There has also been at least one death blamed on water beads: a 10-month-old in Wisconsin who died in July 2023.

The CPSC in September issued a strong warning to families to keep water beads out of any place where babies and young children might be.

“Regulation of water beads is the logical next step and I anticipate the CPSC starting the process in the coming year,” CPSC Chair Alex Hoehn-Saric told U.S. PIRG Education Fund.

Just this week, Congressman Frank Pallone Jr., (D-N.J.) announced plans to introduce legislation banning water beads marketed to children.

Read more

Ashley Haugen wishes they never existed. It’s been six years since her 10-month old daughter Kipley swallowed some small colorful water beads that belonged to her older sister. That was the beginning of the Texas family’s nightmare during the hours it took for the beads to be discovered and surgically removed, and the weeks after that as Ashley and her husband realized Kipley suffered from brain damage.

It also began Haugen’s mission to warn other parents and regulators about the dangers of water beads through her non-profit organization, That Water Bead Lady.

Haugen has spent the years learning about the science and the marketing and the lack of understanding and resources.

Unfortunately, other children have since been injured and at least one died this year after ingesting the squishy beads, which – when wet – can grow from the size of an ice cream sprinkle to an inch in diameter or larger – even 100 times their original size – and cause an intestinal blockage.

Haugen and other parents whose children were seriously hurt after swallowing a water bead met last spring with Hoehn-Saric, along with Commissioners Mary Boyle, Peter Feldman and Richard Trumka, to plead for water beads to be better regulated or even banned.

Water beads are often sold in packages of 30,000 to 50,000. They’re tiny. They roll. They stick in hidden places. “Dry water beads can be the size of a pinhead, making them nearly undetectable if dropped on the floor or spilled in a playroom,” the CPSC says in an advisory on its website.

In September, the first recall of water beads since 2013 was announced after a 10-month-old Wisconsin baby died and a 9-month-old baby in Maine was seriously injured after swallowing one of the water beads. About 52,000 Chuckle & Roar Ultimate Water Beads Activity Kits were recalled. The water beads were sold by Target for about $15 from March 2022 through November 2022.

More importantly, the CPSC signaled more regulation and restrictions of water beads are coming. The risk is not limited to a single product, Hoehn-Saric said.

“I am deeply concerned about the hazard posed to small children from water beads,” Hoehn-Saric said. “This year we issued a recall of one water bead product following the death of a small child. We also made clear in our public messaging that water beads should never be in homes or other spaces where babies and small children may spend time.”

Haugen takes some comfort knowing her message is getting out. “I am hearing an overwhelming uproar from families across the country, signaling the increasing surge in awareness about the dangers of water beads,” she told U.S. PIRG Education Fund.

“As a parent it is deeply unsettling to discover water beads in unexpected places, like ticking time bombs around your home, or utilized as sensory toys in your child’s school or therapy clinic without your knowledge or consent.”

Based on all of the conversations Haugen has had with families across the country, she said it’s important to realize that an injury from a water bead “can happen to any family. … Implying that better supervision or cleaner homes is the solution to preventing these incidents is misleading.”

Haugen’s goal is to get water beads banned and to warn families who may already have them in their homes.

Gowda of Kids In Danger said water beads are not worth the risk.

“No amount of supervision can keep children safe from water beads. Even if you’re buying them for older kids, the tiny beads can spread in the home and a younger child may get hold of them,” Gowda said.

“Get rid of any you have in your home now and then stay vigilant because families have reported that they continue to find water beads even years later.”

RECALLED TOYS FOR SALE

One of the most frustrating and senseless dangers in Toyland is the sale of toys that have already been recalled because they’re dangerous. Sometimes the toys have small pieces that can break off easily and choke or cut a child. Other times the toys contain excessive levels of lead.

In any case, once a toy or any other product has been recalled, it’s illegal for anyone to sell it. This problem has existed for years. In last year’s Trouble in Toyland report, we documented how easy it is to buy recalled toys. U.S. PIRG Education Fund bought, paid for and received more than 30 recalled toys from a variety of online retailers.

We conducted a similar experiment this year, on a smaller scale, by buying five toys of the 17 toys that had been recalled this year. Once again, it was too easy.

We bought toys from three online retailers.

They are:

- Silver Lining Cloud Activity Gym by Skip Hop, recalled Feb. 9, 2023. Purchased Oct. 6, 2023, through Facebook Marketplace.

- Calico Critters Animal Figures by Epoch Everlasting Play, recalled March 9, 2023. Purchased Oct. 14, 2023, through eBay.

- Basket with Balls by Monti Kids, recalled April 6, 2023. Purchased Oct. 2, 2023, through eBay.

- Baby Shark Sing & Swim Bath Toys by Zuru, recalled June 22, 2023. Purchased July 28, 2023, through eBay.

- Rainbow Road board book by Make Believe Ideas, recalled Sept. 21, 2023. Purchased Oct. 1, 2023, through Little Giant Kid.

TRACKING DOWN RECALLED TOYS

To check whether toys you’re considering buying or toys already in your home have been recalled, go to cpsc.gov/recalls

TO CHECK ON A TOY BEFORE YOU BUY

Do a keyword search on saferproducts.gov

The CPSC and members of Congress have also stepped up attention on products for sale after they’ve been recalled.

In August, a bi-partisan group of representatives in Congress wrote letters to 17 companies, including Meta (Facebook,) Amazon, Walmart, Target, Ebay and Poshmark. The letters noted that online marketplaces are expected to prevent the sale of recalled products through their sites. The letters said the companies have “been falling short on this mission.”

Read more

The letters were sent by House Energy and Commerce Committee Chair Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-WA); Full Committee Ranking Member Frank Pallone, Jr. (D-NJ); Innovation, Data; Commerce Subcommittee Chair Gus Bilirakis (R-FL); and Subcommittee Ranking Member Jan Schakowsky (D-IL).

A few months earlier, in April, CPSC Chair Alex Hoehn-Saric sent his second letter in as many years to Facebook/Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg. The message was about the same as in the 2022 letter.

Much of the ire has stemmed from sales of recalled Rock ‘n Play rockers, which have been connected to about 100 infant deaths in recent years. But the principle – that it’s illegal to sell recalled products – applies to all products, including toys.

“Facebook is uniquely positioned to identify recalled and violative products … and stop their sale before they are listed,” Hoehn-Saric wrote. “Moreover, at best, CPSC is catching these unlawful products after they have been listed for sale and made available to the public; we do not know how many illegal sales occurred that we did not identify. … If CPSC staff can identify these illegal listings using your site, Meta indisputably can prevent them from appearing in the first place.”

To carry that further, if U.S. PIRG Education Fund can so easily find and buy recalled toys, why can’t these companies update their sites once a week to reflect the CPSC’s newly recalled products? Of course they can. For the products we bought, the listings weren’t even misspelled. Some had been recalled months before. For last year’s investigation, some of the products had been recalled a year or two before.

And some of these sites allow you to save searches and get email alerts when a new product matching those keywords is listed. So they can do that but not flag those listings? Of course they can.

The other question is why some companies, such as T.J. Maxx, Home Depot, Best Buy and Meijer have faced multi-million dollar civil penalties for selling recalled products, but companies such as Facebook Marketplace and eBay haven’t?

“Under CPSC’s statute, different safety obligations apply when a company is a manufacturer, distributor, private labeler, or retailer of goods,” Hoehn-Saric told U.S. PIRG Education Fund. “Online marketplaces that host third-party sellers don’t fit neatly into one of those categories for most of their operations.”

It may come down to Section 230 of the 1996 Communications Decency Act, which some say insulates online platforms from being responsible for products sold illegally on their websites. It says: “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.”

Now, many would say that publishing opinions is one thing and allowing the illegal sale of goods is something else. Still, if Congress would amend the law, or the question would be resolved in a court case, the CPSC would have more clarity to pursue enforcement against platforms such as Facebook Marketplace and eBay, just like the regulator does with big box retailers.

CPSC Commissioner Peter Feldman told U.S. PIRG Education Fund that something needs to change with these online companies. “The status quo can’t stand,” he said. “It’s clear there’s more they can do and should be doing to keep their users safe. These firms absolutely have the resources necessary to prevent these transactions.”

If these online retailers continue to allow the sale of recalled products, the CPSC may try a different tactic than just sending letters, Feldman said. “All options are on the table.”

Aside from the interpretation of the law that may protect online retailers for now, there’s certainly no reason the companies couldn’t voluntarily block the sale of recalled products, as they do with other products they’re not allowed to or don’t want to sell, such as guns, animals or drugs.

“Yes, I share your concern about recalled, non-compliant, and dangerous products online,” said Hoehn-Saric, the CPSC chair, told U.S. PIRG Education Fund.

That’s why he met with six of the largest online marketplaces in the last year, including eBay and Facebook Marketplace, to urge them to work with the CPSC.

“Online marketplaces can and should adopt common sense practices to protect consumers,” Hoehn-Saric said. “This includes prioritizing product safety within the companies and vetting sellers and products that platforms allow to be sold on their sites. Some companies are taking steps in the right direction, but clearly not enough is being done.”

For now, the CPSC is playing whack-a-mole. When listings for recalled products are found or reported to the CPSC, the regulator issues “take-down requests.”

The CPSC issued more than 57,000 take-down requests to e-commerce platforms in FY23, with the vast majority of those going to Facebook Marketplace.

“This reliance on industry’s good will,” Hoehn-Saric said, “is not a long-term solution to the problem.”

TO FILE A COMPLAINT

If you have a serious incident with a toy,

you can alert the CPSC by filing a report

on saferproducts.gov

WHY ARE TOYS RECALLED ANYWAY?

Toys are recalled either after defects or injuries have been reported to the company or the CPSC, or if the CPSC finds a problem through random testing. Recalls are almost always voluntary, in cooperation with the CPSC, because mandatory recalls generally have to go through a court.

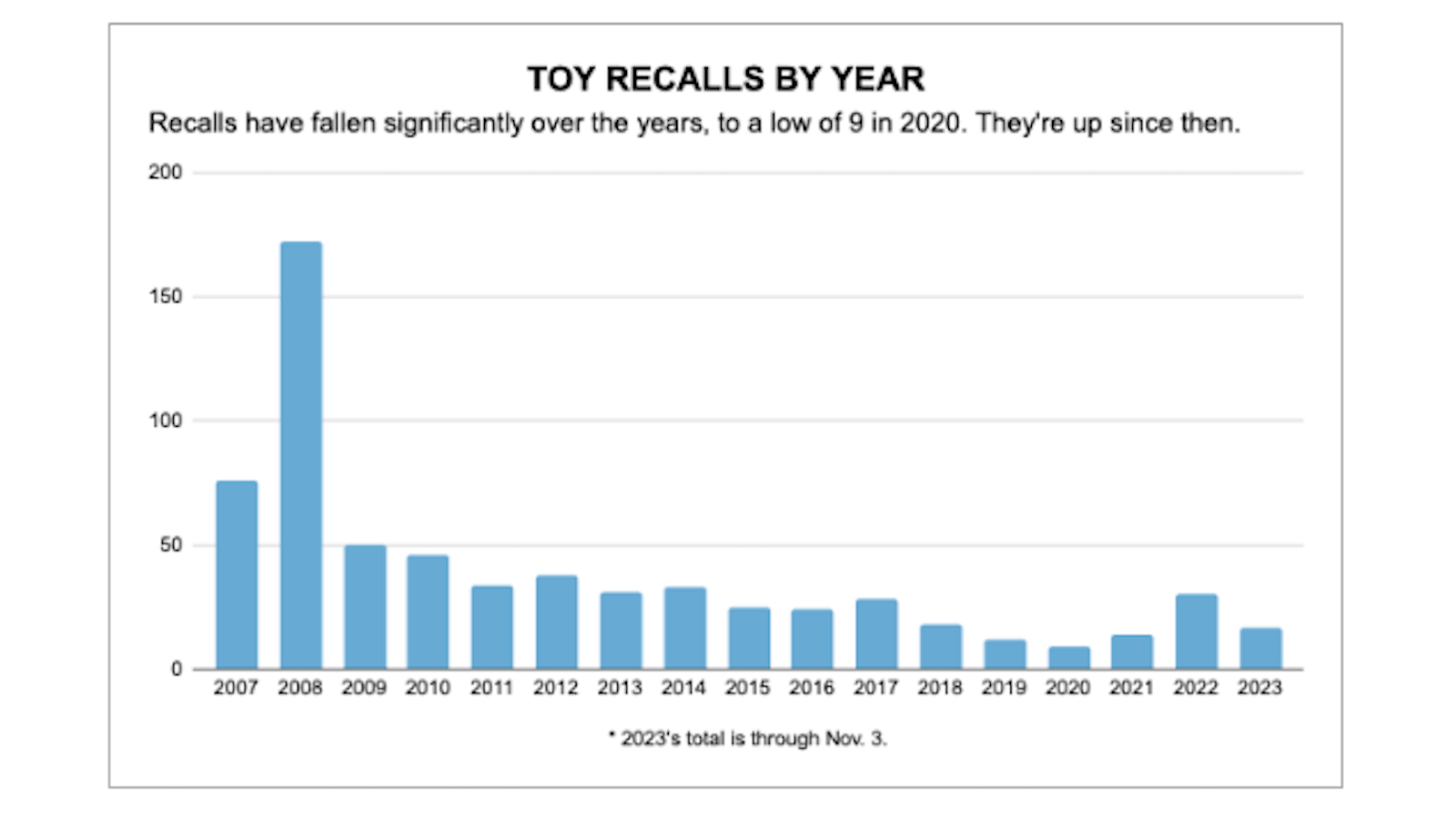

Toy recalls have declined significantly in the last 15 years. In 2007, there were 76 recalls. That jumped to 172 recalls in 2008. Recalls declined gradually after that, to a recent low of only nine recalls in 2020. Last year, there were 30. So far this year, through Nov. 3, there have been 17.

Read more

The expectations for toys are high. “All children’s toys manufactured or imported on or after February 28, 2018, must be tested and certified to ASTM F963-17 (ASTM International was formerly known as American Society for Testing and Materials,” the CPSC says.

Further, “all toys intended for use by children 12 years of age and under must be third-party tested and be certified in a Children’s Product Certificate as compliant to the federal toy safety standard enacted by Congress,” the CPSC says. The laboratory must be one accepted by the CPSC.

The standards vary depending on the type of toy and the age group it’s marketed to.

BUTTON BATTERIES

Four years after 18-month-old Reese Hamsmith died because she ingested a button battery from a remote control, a law named after her will take full effect. Reese’s Law will require stronger safety procedures for products that use button or coin batteries, such as key fobs, bathroom scales, game controllers, tealight candles and greeting cards, effective March 19, 2024. The law also requires packages containing replacement batteries to comply with child-resistant packaging.

The CPSC in September 2023 approved final standards aimed at reducing the threat to children 6 years old and younger by requiring compartments holding button batteries to be more difficult to open. Opening these compartments must require something like a screwdriver or coin, or two separate, simultaneous movements by hand.

The new battery standards don’t apply to toys for children less than 14 years old if the toys adhere to the Toy Standard.

If swallowed, button batteries “can burn through a child’s throat or esophagus in as little as two hours,” the CPSC says.

Read more

About 54,300 people went to emergency rooms from 2011 through 2021 after button or coin batteries were ingested or inserted in their body, such as through their nose or ear, according to CPSC estimates based on data from the National Electronic Injury

Surveillance System. Victims are usually children 4 years old and younger.

At least 32 deaths are blamed on button batteries from Jan. 1, 2011 through March 31, 2023, including three last year and two in the first three months of this year.

CPSC Commissioner Richard Trumka noted in a statement the CPSC gave product manufacturers six months to comply after its September 2023 vote. “But make no mistake: manufacturers shouldn’t wait six months — I expect them to comply with the rule ASAP. Compliance with CPSC’s rule on button and coin cell batteries will save lives.”

The new rules for battery compartments and packages of replacement batteries will better protect children. It’s still important for parents and caregivers to make sure compartments are secure and that young children can’t access discarded or replacement batteries.

CHOKING HAZARDS AND LABELS

From 1980 to 1995, nearly 200 children died after choking on balloons, small balls or marbles. All of those products now must adhere to the revised labeling requirements.

In 1994, about 5,000 children were treated in emergency rooms after swallowing or aspirating toys or pieces of toys. That’s a stunning number. And of the 18 toy-related deaths in 1994, 13 were blamed on choking.

Read more

The CPSC launched a massive labeling campaign. By Jan. 1, 1995, all newly manufactured toys intended for children 3 to 6 years old had to be labeled as a choking hazard to children younger than 3. The change was aimed at saving lives.

In 2021, one child died from choking on a toy, according to the CPSC. The 17-month-old boy swallowed a plastic toy, which was part of a playset. Still, though, more than 9,000 children age 4 or younger were treated in emergency rooms in 2021 for ingesting a toy or a piece of a toy.

To determine whether a toy or part could be a choking hazard, check whether it can fit through a cardboard toilet paper roll. If it does, it could be swallowed by a child.

Toys that contain small parts and pose a choking risk must be labeled that they’re not safe for children less than 3 years old, as the ones below are labeled prominently.

COUNTERFEIT TOYS

Counterfeit toys continue to infiltrate retailers’ shelves and online platforms, with many coming in from overseas. Counterfeit toys can’t be assumed to meet stringent, mandatory U.S. safety standards, which require that all toys designed for children 12 and younger “must be third-party tested, be certified in a Children’s Product Certificate and comply with the federal toy safety standard enacted by Congress,” the CPSC says.

There are more than 100 safety standards and tests required for toys. It is reasonable to assume that counterfeiters don’t worry about those important safety standards and testing.

Read more

In fiscal year 2022, CBP seized 381 shipments of toys worth $7 million for copyright infringement, meaning they’re counterfeits.

One shipment seized on a given day could contain hundreds or even thousands of the same item.

Last year’s seizures are up from 284 shipments the year before, an increase of 34%.

“Legitimate toy companies spend significant resources to bring their products to market – including steps to certify their products are safe,” said Joan Lawrence, senior vice president of standards and regulatory affairs for The Toy Association, the industry’s trade association.

“However, under current law, sellers on third-party online marketplaces are unfortunately able to operate anonymously and take advantage of consumer faith by selling products that may be counterfeit, stolen, or recalled and may not comply with safety laws – putting our children at risk.”

The Toy Association has been urging Congress to pass stronger laws, aimed in particular at online marketplaces that sell all kinds of products, whether they’re counterfeit, stolen or recalled.

Congress did pass the INFORM Act aimed at counterfeit and stolen goods, but it only cracks down on higher-volume sellers.

Counterfeit products can pose other risks, Lawrence said. They may not be appropriately age-labeled, especially if they have small parts, and they’re often made of materials of poor quality that can put children at risk.

Counterfeit smart toys are a growing problem as smart toys become more popular.

“It may be tempting to purchase one online at a low price from an unknown seller,” Lawrence said. But these toys may violate FTC guidelines and federal children’s privacy laws, she said.

CHILDREN OF DIFFERENT AGES IN THE HOME

It can be challenging to make sure children of different ages don’t have access to toys they shouldn’t. A child less than 3 shouldn’t be around, for example, dolls with tiny accessories or small parts of a building set. Children who are 5 or 6 should not be able to access a chemistry set.

“Remember, the age-grading isn’t about how smart your child is,” Lawrence said. “It’s safety guidance that’s based on the developmental skills and abilities of children at a given age, and the specific features of the toy.”

Rose, the emergency room doctor, said it’s important to educate older children about safe storage of toys, and make sure younger children are closely supervised.

HIGH-POWERED MAGNETS

In May 2023, a 2-year-old boy required surgery to repair a bowel obstruction caused by two tiny, colorful magnets that he had swallowed.

Two months earlier, in March, a 9-year-old girl had to have tiny, 5 mm magnets removed from her nose at a hospital after she and her friends were simulating nose piercings when magnets went up her nose.

Cases such as these are the reason the CPSC in 2022 adopted new rules for magnets.

Read more

The tiny, colorful magnets are often marketed as fidget toys. But they caused 26,600 children to be rushed to hospital emergency rooms from 2010 through 2021, according to the CPSC. At least seven children have died after ingesting high-powered magnets. The problem: if two or more magnets are swallowed, they can connect and pinch internal tissue together and cause serious issues such as intestinal blockage or blood poisoning.

Effective last year, federal standards now require magnets that are loose or able to come out of products to be either too large to swallow or weak enough to reduce the risk they’ll connect inside the body if two or more were swallowed. If magnets fail the CPSC’s small parts cylinder test – any object fits completely into a test cylinder 2.25 inches long by 1.25 inches wide, then they must have a flux index (a measurement of strength) of less than 50 kG2 mm2.

Despite the new standards, these dangerous magnets are still in many, many homes.

TOY-RELATED INJURIES

The CPSC tracks overall toy-related injuries and deaths involving people of all ages, and provides breakdowns for 14 years and younger, 12 years and younger and 4 years and younger. The statistics reflect people treated in U.S. hospital emergency rooms.

The overall number of injuries increased for 2022, according to a CPSC report released Nov. 14. About 209,500 toy-related injuries were treated in U.S. emergency rooms in 2022.

Of those:

- 76% – about 159,500 – were sustained by children 14 years old or younger;

- 69% were sustained by children 12 years old or younger;

- 38% were sustained by children 4 years old or younger.

- Males accounted for 54% of the injuries.

The incidence of injury was greatest among children 4 years old and younger: 432 out of every 100,000. That compares to 267 out of every 100,000 children 14 and younger and 63 out of every 100,000 people of all ages.

About 94% of toy-related injury patients were treated and released.

As for the types of injuries:

- 41% were classified as lacerations or contusions/abrasions.

- 46% were to the head and face area.

- Non-motorized scooters were connected with the largest number of toy-related injuries for all ages among products classified as toys.

There were 11 toy-related deaths among children 14 and younger in 2022: Five were related to balls, including choking on bouncy balls and blunt force trauma to the head. Others involved balloons, stuffed animals or other toys.

There is good news: The numbers of toy-related injuries for children 14 and younger decreased significantly — by more than 10% since 2015, the CPSC said.

Injuries and incidents occur when:

- Toys don’t meet standards, such as if they have parts that can easily be removed or break off and be ingested.

- Children get access to a toy not meant for a child their age, such as a small bouncy ball or building blocks.

- Children use a toy in a way that wasn’t intended.

- Counterfeit toys are purchased.

- Toys violate our children’s privacy.

Toys that don’t meet standards or wear over time is the reason parents and caregivers should inspect new toys and consider whether a particular toy is appropriate for their child right now, said Dr. Jerri Rose, associate division chief of pediatric emergency medicine, at UH-Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital in Cleveland.

Issues to consider:

- Are there small parts that can break off that the child could put in their mouth? A small part is defined by the CPSC as any object that fits completely into a test cylinder 1.25 wide by 2.25 inches long. The diameter of a toilet paper tube works for a home test. This is about the size of the fully expanded throat of a child less than 3 years old.

- Could a piece of the toy break off easily and produce something sharp that could cut the child or poke an eye?

- What does the label on the box or package say? When a toy is approved and meets standards, it should say what age it’s approved for, Rose said.

- Does the label say non-toxic?

- If the toy involves electricity, does it say it’s UL-approved?

- If there are batteries, especially button batteries, are the compartments secure so they can’t be opened by a young child. Screws can come loose during shipping.

- Is your child old enough to play with the toy responsibly? Just because a child is older than 3 doesn’t mean he can automatically be trusted to not put small parts in his mouth. Parents know their children best.

RECOMMENDATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS

- We support the bipartisan COPPA 2.0, introduced this year, which updates the 1998 Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act to better protect kids’ and teens’ privacy online, particularly regarding data collection, advertising and a parent’s ability to delete their child’s information on file.

- We support the bipartisan TOTS Act, which would require companies that sell high-tech smart toys to clearly label on the box if it contains a Wi-Fi connection and the ability to gather data on children. It was introduced in January 2023.

- We support the bipartisan Informing Consumers About Smart Devices Act (S. 90), which would require manufacturers of everyday household products such as refrigerators and power tools to disclose to consumers prior to purchase if the products have audio or visual recording components and can transit data through Wi-Fi.

- We support the Sunshine in Product Safety Act, which would allow the CPSC to warn consumers more quickly about all kinds of dangerous products, including toys, in advance of a recall. It was reintroduced in March 2023.

- We celebrate enactment of the federal INFORM Act, which took effect in June 2023. It’s aimed at cracking down on U.S. sellers that allow counterfeiters and thieves. Now we’re watching for compliance and enforcement.

- The CPSC should step up enforcement and impose meaningful penalties against merchants that sell counterfeit or recalled toys, or fail to promptly report complaints about product-related injuries.

- The CPSC should get clarity on whether federal law allows online retailers such as Facebook Marketplace and eBay to sell recalled toys without the same multi-million-dollar consequences that regulators impose on brick-and-mortar retailers.

- Toy manufacturers should make a commitment to do a better job of adhering to existing toy safety standards and improving testing.

- Merchants should do more to prevent recalled toys and counterfeit toys from being sold.

- The CPSC should continue to research the risks of phthalates and other toxics often found in toys made of plastic. Phthalates make plastic softer and more flexible.

- Lawmakers should pass stronger data privacy laws, explicitly prohibiting companies from gathering more data from consumers than is necessary to deliver the service a consumer is expecting to get, and use it for any secondary purposes, especially for data that could be generated while using a VR headset.

Toy safety tips for families and gift-givers

Take the next step to help support our work.

Using the time-tested tools of investigative research, media exposés, grassroots organizing, advocacy and litigation, PennPIRG Education Fund, a 501(c)(3) organization, stands up to powerful interests and delivers concrete results. But we need your support to keep our work going strong.

As threats to the public interest grow, our work becomes more important every day. Every contribution powers our research, fuels our advocacy, and sustains our future.

Topics

Authors

Teresa Murray

Consumer Watchdog, U.S. PIRG Education Fund

Teresa directs the Consumer Watchdog office, which looks out for consumers’ health, safety and financial security. Previously, she worked as a journalist covering consumer issues and personal finance for two decades for Ohio’s largest daily newspaper. She received dozens of state and national journalism awards, including Best Columnist in Ohio, a National Headliner Award for coverage of the 2008-09 financial crisis, and a journalism public service award for exposing improper billing practices by Verizon that affected 15 million customers nationwide. Teresa and her husband live in Greater Cleveland and have two sons. She enjoys biking, house projects and music, and serves on her church missions team and stewardship board.

R.J. Cross

Director, Don't Sell My Data Campaign, U.S. PIRG Education Fund

R.J. focuses on data privacy issues and the commercialization of personal data in the digital age. Her work ranges from consumer harms like scams and data breaches, to manipulative targeted advertising, to keeping kids safe online. In her work at Frontier Group, she has authored research reports on government transparency, predatory auto lending and consumer debt. Her work has appeared in WIRED magazine, CBS Mornings and USA Today, among other outlets. When she’s not protecting the public interest, she is an avid reader, fiction writer and birder.

Find Out More

Food for Thought 2024

Safe At Home in 2024?

5 steps you can take to protect your privacy now