Tell the FTC: Stop tech companies from selling kids’ data

VR risks are significant enough the child health experts we spoke to recommend parents steer clear of Meta's Quest VR headsets

Sign the petition

Director, Don't Sell My Data Campaign, U.S. PIRG Education Fund

Master's Policy Research Intern

Virtual reality (VR) headsets are growing in popularity and might be at the top of your child’s holiday wish list this year. It makes sense – they can be pretty neat, and Meta, the company selling the most VR headsets, recently lowered the recommended age to 10-years-old in a push to win a younger market.

As a part of our annual Trouble in Toyland report, PIRG tested Meta’s newest VR headset, the Quest 3, and its kids accounts for ages 10 to 12. We found that while these accounts increase parental controls, they still fail to address some pressing problems, including access to inappropriate content. The company has also yet to release any testing proving VR technology and content is safe for minors in the first place.

The child health experts we spoke to recommend parents approach VR using the precautionary principle: don’t use it until we know it’s safe for developing brains, and Meta (formerly Facebook) proves we can trust it with our children and teens.

VR stands for “virtual reality”. Putting on a wearable console system allows you to see and interact with a 360-degree computer-generated world. Inside the headset you’re completely surrounded by whatever virtual content you load up, including surround sound. To look at a virtual sky, you look up. If someone shoots a gun behind you, it sounds like it went off behind you.

Everything in VR feels a lot more real and more intense than on 2-D screens. It’s like you’re inside of a game.

Meta – the company formerly known as Facebook and currently the biggest VR seller – in October released its latest model of VR headset, the Quest 3 (currently selling at $499.99). The company recently changed the headset’s original branding from Oculus to Quest.

PIRG campaign director R.J. Cross demonstrates the Meta Quest 3.Photo by Tim O'Connor | TPIN

Meta has two other models of Quest headset: the Quest 2 (released in 2020, currently $299.99), and the professional grade Quest Pro Mixed-Reality headset (currently $999.99). You can also buy refurbished Quest 2 headsets at a discount.

Quest headsets are how you access what CEO Mark Zuckerberg calls “the metaverse” – a new iteration of the internet where everything is 3-D. Right now, a lot of it is about gaming.

On Meta’s Quest app store you can buy, download and use third-party apps and games with your VR headset. You can play 3-D golf or ping pong, get in a bar fight, ride along on the Apollo 11 mission, power wash a house (oddly), or shoot a sniper rifle as a World War II soldier. You can play by yourself or with others, and use your microphone to have conversations with other players.

Meta has taken multiple steps this year to get more kids using its Quest headsets, despite concerns raised by child health experts and lawmakers.

First, in April 2023, Meta announced it was lowering the age for Horizon Worlds – Meta’s primary VR social app – from 18 down to 13. Then 2 months later, Meta announced it was lowering the recommended age for its headsets from 13 down to 10, shortly after announcing the release of its latest Quest 3 model in time for the holidays.

Meta’s Quest headsets have yet to gain widespread traction, and its moves to get more children onto its VR platform come at a time when the company’s business practices and effects on young users have come under intense scrutiny. In October, 42 state attorneys general from across the political spectrum sued Meta for allegedly ignoring internal research about the negative impacts of its social media product Instagram on teens.

Virtual reality, like all technology, is a tool. And this tool is very, very new.

“At the risk of sounding cliche, it really is like the wild west,” Dr. Brett P. Kennedy, a children’s clinical psychologist and co-director of Digital Media Treatment & Education Center said in an interview with PIRG.

“We know there are potentially big impacts on kids and teens,” said Dr. Mark Bertin, developmental pediatrician and assistant professor of pediatrics at New York Medical College told us.

Until we know more, it just isn’t worth the risk right now.Dr. Mark Bertin

developmental pediatrician and assistant professor of pediatrics at New York Medical College

“The amount of technology in our children’s lives is already impacting their mental health,” Dr. Bertin said. “Introducing yet another piece of technology – especially one as novel and engaging as virtual reality – could have real ramifications for the development of long-term social-emotional well being, cognitive skills like focus, and for regulating behavior in general.

Until we know more, it just isn’t worth the risk right now,” he added.

We’ve found 6 main reasons for caution:

There’s just starting to be research on VR and its effects on the body and brain. What’s out there shows we need a lot more studies.

For example, in a 2019 interview, UCLA researcher Dr. Mayank Mehta recounted a study he did scanning the brains of rats as they used VR. The rats’ brains behaved in really unexpected ways: 60% of the neurons in the hippocampus – a part central to navigating our surroundings – “simply shut down in virtual reality”, and the other 40% of the neurons seemed to fire randomly. Though not conclusive, this result suggests using VR can trigger abnormal brain function. Over time, this raises the possibility the brain might rewire itself in unpredictable or even harmful ways.

Professor Mehta emphasized his study did not conclude anything definitively, either good or bad. But he added that “the long-term consequences are really hard to measure in the human brain because humans age very slowly.”

Using VR may trigger abnormal brain function. This could possibly cause the brain to rewire itself in unpredictable or even harmful ways.

“We can’t wait for 40 years, for teenagers who are today using virtual reality to see what happens to them when they’re 60,” said Professor Mehta. He emphasized the need for further studies.

Researchers have repeatedly found it’s easy for minors to access inappropriately violent or sexually graphic spaces when using Quest headsets. We found even content that’s rated ok for 10-year-olds downloadable from the Meta Quest app store can be disturbing.

“Content that’s not developmentally appropriate can be very harmful,” said Dr. Bertin, the developmental pediatrician. “You can’t unsee things.”

PIRG tested Meta’s new kids’ accounts for ages 10 to 12. These accounts allow parents to control what apps their child downloads, and Meta turns off access to certain age inappropriate apps by default. Those controls are good – but not good enough.

Playing on a Meta Quest 3 headset as a 10-year-old, PIRG researchers tested Rec Room, an app that’s rated “E for Everyone ages 10 and up” and currently one of the most popular apps available in Meta’s Quest app store. The app quickly recommended that our “10-year-old” play a game of Russian Roulette with real players sitting around a table in a darkened room, passing a gun around and deciding who to shoot. Within moments, a player sitting across from our virtual 10-year-old shot himself in the head.

The VR app Rec Room recommended our 10-year-old test account play Breaking Point, a game of Russian Roulette where players choose whom around the table to shoot.Photo by PIRG staff | TPIN

The games on Rec Room take place in relatively cartoon-ish settings. The 3-D experience, however, makes everything feel a lot more intense. It also doesn’t change the fact there are other real people around your child who may make bizarre or disturbing choices.

In addition to Russian Roulette (called Breaking Point on the app), Rec Room also recommended our test 10-year-old explore horror games and first-person shooters including Recoil Arena, Survive Mr. Beast, Vietnam Warzone, and Reynosa PVP, a first-person shooter on the U.S.-Mexico border.

Popular apps available on Quest headsets can host sexually graphic content. A BBC News researcher using VRChat – a prominent app on Meta’s app store with a minimum age rating of 13 – posed as a 13-year-old girl and was able to access virtual strip clubs and explicit rooms where players simulated sex. The non-profit group Center for Countering Digital Hate found a similar problem with Horizon Worlds – Meta’s own social VR app – with minors present in sexually explicit places like virtual strip clubs, private rooms designed for simulating sexual acts, and bars offering sex toys for players to interact with.

These spaces can be dangerous. They exist so users can interact with each other. Teens exploring or stumbling on these spaces are likely to interact with adult users.

Some of the most popular apps – including Rec Room, VRChat and Meta’s own Horizon Worlds – are large multiplayer worlds where anonymous users create their own games and players interact with one another continuously, across all ages.

After parents allow a child or teen to access one of these multiplayer worlds, helping moderate their experience becomes a much more involved process. For example, Rec Room’s Quest app store page boasts “MILLIONS of player-created rooms.”

Content inside these apps may be labeled to try and differentiate what’s appropriate from what’s not. Those labels, however, are usually assigned by the users who create the content, as in the case of Rec Room. There’s no guarantee that user-moderators will set age restrictions or content warnings that all parents would agree does an adequate job.

Apps that encourage free play and creation can have their upsides, particularly when the app is designed with children in mind, such as Roblox. Other of these apps, however, cater to a more adult audience and allow children and adults to mingle.

Meta’s VR Quest platform builds off the company’s history and expertise as a social media company. As CEO Zuckerberg explained in a 2021 interview, from the very outset the company saw its VR being “about social connection more than it’s about whatever the technology is.” Providing social experiences is “really where our bread and butter as a company is,” said Zuckerberg.

Similar to Facebook or Instagram, people can “friend” your Meta Quest account, and the Quest sign-up process includes a nudge to link your Facebook or Instagram account to your VR. All of the most popular games in Meta Quest’s app store that are free to download are also multiplayer (as of early December 2023). Many are open world apps with a heavy emphasis on interaction, allowing players to “friend” or “follow” others, and use chat or microphone features to have real-time conversations. This includes Meta’s social VR app, Horizon Worlds.

Meta currently paints the metaverse as a tool to “help you connect with people when you aren’t physically in the same place and get us even closer to that feeling of being together in person.”

There’s no doubt social interaction online can be a positive thing. In our testing, however, we found we don’t particularly want to get closer to the feeling of being together in person in the current popular Quest spaces.

Our testing found negative social interactions with others on Quest are not uncommon. Other researchers have had more extreme negative encounters including sexual harassment.

It likely won’t surprise parents of kids and teens who play online multiplayer video games with chat and voice features that profanity is a common feature in VR games, too.

In PIRG’s testing of the popular app Rec Room, for example, our researcher’s 10-year-old user with a junior account managed to stumble on bad language, despite the fact Rec Room automatically disables audio for junior accounts. Our fake 10-year-old happened to walk by a whiteboard where a player was repeatedly drawing genitalia and the phrase “s*** my d***”.

Unfortunately, hateful speech continues to be an issue in VR multiplayer games as well. The same user at the whiteboard proceeded to write other racially motivated profanity, and someone had already drawn a swastika.

Our “10-year-old” experienced a bit of disorienting bullying in the majority of the games he played on Rec Room. In the very first game we tried – Snipers vs. Runners – our junior account shook hands with another player, thus becoming friends and able to locate each other inside Rec Room instantly at any point that we were both logged on. After shaking hands, the other player began to slap the PIRG junior account player repeatedly, following when we tried to move away. The game began another round, separating us from the other player. The moment the round ended, however, all players were dumped back in the waiting room together, and the same player ran up and began slapping our junior account player again. This went on for three rounds before we’d had enough.

We later had similar experiences inside the Rec Room games Breaking Point and The Fog is Coming.

PIRG’s 10-year-old junior account player in his hour on Rec Room did not experience any sexual harassment or assault, thankfully. However, other researchers have documented this happening to teen accounts.

The Center for Countering Digital Hate’s testing of Meta’s own social VR app Horizon Worlds documented minors receiving solicitations to send suggestive photos from adults.

Playing on a young teen account, Franz was chased by another player who attempted to sexually assault her avatar.

Researcher Rachel Franz at the children’s advocacy group Fairplay shared with PIRG her experience testing the app VRChat with a 14 year old girl’s account. “In one word: horrible,” she said. Playing on the young teen account, Franz was chased by another player who attempted to sexually assault her avatar.

Franz emphasized the physical realness of VR made the assault attempt a lot scarier. “Being pursued feels real,” Franz said. “And the psychological and psychological impact is real. Even after I took the headset off, my heart was racing. That moment has stayed with me.”

Franz said VRChat’s function for blocking another user from interacting with you was difficult to use in a stressful situation. “You have to click on a moving target while being chased and having profanities screamed at you,” she said. “In that moment, it was practically unusable – and I’m an adult with a fully developed sense of coordination” which younger players might not have yet.

Fairplay has forthcoming research next year on marketing practices in VR apps available for use with Meta’s Quest headsets.

It’s good that when it comes to its youngest users, Meta has more safeguards in place. As of this writing, children under 13 can’t accept follow requests for their Quest account from other users. (It’s worth mentioning, however, that Meta emphasizes this is the case “at this time” and “for now” in its materials – so its position in the future may change.)

Even with the current protections, however, parents may have to put in extra work to set app-specific parental controls to protect their kids. Meta explains that even if your child uses an account for a 10- to 12-year-old, third-party “[a]pps may have social features such as messaging, voice, photo sharing, video, and the ability to meet and interact with others in the same virtual space, that could allow your child to interact with people they may not know.”

In our test of the app Rec Room, for example, our fake 10-year-old user with both a junior Meta and a junior Rec Room account could make friends with other players without approval from a parent, and received in-game gifts from strangers – something which could make some parents uneasy. (It is nice, however, that Rec Room disables junior accounts from using voice or chat features.)

Our 10-year-old test account receives a gift from a stranger.Photo by PIRG staff | TPIN

One of the biggest draws of VR is just how immersive the experience is compared to 2-D. VR feels so real it’s even being used for exposure therapy for people with phobias. But the power of VR’s realness is exactly why its use for social interactions and commercialized entertainment – especially for minors – raises concerns.

“If it feels that real, how you use it really matters,” clinical child psychologist Dr. Kennedy said in an interview with PIRG. “While the experience in VR can feel amazing, the negative physical and emotional consequences can be significant and shouldn’t be overlooked.”

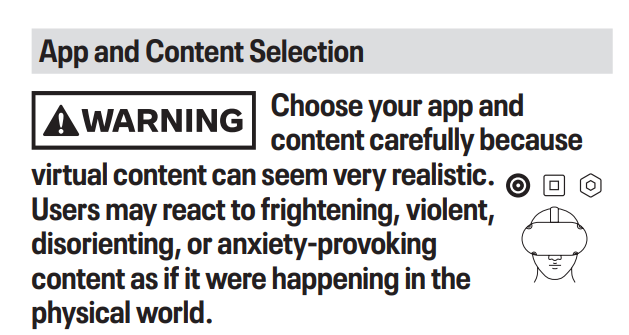

As Meta puts it, users may react to VR experiences “as if it were happening in the physical world.”

Meta’s own warning about the intensity of VR content in its health and safety guide.Photo by PIRG staff | TPIN

Research suggests 3-D VR content impacts both a player’s physiology and emotional state in bigger ways than typical content. A 2021 study found that those playing a game in VR reported stronger negative emotions than participants who played the exact same game on a laptop’s 2-D screen. The VR users’ negative emotions lingered throughout the day, well after use.

While the experience in VR can feel amazing, the negative physical and emotional consequences can be significant and shouldn't be overlooked.Dr. Brett P. Kennedy

children’s clinical psychologist and co-director of Digital Media Treatment & Education Center

The immersiveness factor should prompt parents to revisit what content is ok for their child. In an interview with CNN, one parent recounted that the violence in a fantasy game played by his 11-year-old son on his Quest headset felt uncomfortably real. The father knew, the story said, that when his son “looked down in VR he was seeing a weapon held in virtual hands, not just a plastic game controller.”

“It bothered me in a way it doesn’t on flat screens even, because they’re doing it with their hands in physical presence,” the parent told CNN.

The intensity of VR content can also amplify the impacts from negative interactions with others, as Rachel Franz of Fairplay recounted in her experiencing an assault attempt in VRChat.

Meta emphasizes that younger children may have more “intense reactions to virtual content and may have a more difficult time distinguishing virtual content from the physical world, even after they stop use.”

Quest headsets come in one size and aren’t designed for kids.

In a 2021 interview about the Quest 2 headset, Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg noted that VR poses some “some pretty fundamental physical challenges” for children. Headsets would need to be weighted and optically aligned for children before it “really makes sense for younger kids to be wearing [them] for an extended period of time,” said Zuckerberg. The Quest 2, he added, was designed for “not small kids, but at least people in their teens and adults.”

Earlier this year, however, Meta lowered the recommended age for Quest from 13 down to 10.

The new Quest 3 weighs just over 1 pound – a little heavier than the Quest 2. According to Meta, it may strain childrens’ neck and back.

Meta’s own health and safety standards also raise the question of eyesight. “Younger children’s visual systems are still developing and may be negatively impacted by using virtual content,” it says.

The Quest headsets include adjustable features to better fit each users’ eyes. However only so much can be adjusted to make it suitable for children. The distance between a child’s eyes (known as interpupillary distance, or IPD) may be too small for the headset’s lens adjustment range, which in turn increases the risk of blurry vision, eye strain, nausea or headaches.

Eye risks don’t go away for teens. Meta notes that Quest headset use may result in blurred or double vision and eye or muscle twitching for all users. A PIRG researcher testing the Quest 3 consistently experienced difficulty focusing her eyes for about an hour after each 20-minute session of headset use.

VR headsets can collect a lot of data, ranging from information we’re used to technology gathering – such as our email addresses – to new kinds of sensitive data that previous technologies have not been capable of gathering, such as our eye or body movements. Equipped with sensors, microphones and cameras, VR headsets can gather extensive amounts of data in very little time. Just 20 minutes using a VR headset generates about 2 million unique recordings of a user’s body language.

The World Economic Forum offers a hypothetical of how this VR data could be abused:

Say the developer of a free VR maze game collects data on how players move their body and how efficiently they solve the maze. An insurance company buys this data from the app developer and analyzes the data of a player that just applied for a life insurance policy. It finds that the player’s movements match patterns of people with very early stages of dementia, and denies the player’s insurance application. The player had no idea that data was being collected when he played the maze game, let alone that it would be sold to an insurance company and used to make a decision about his policy.

Malicious actors could easily set up an innocent looking VR game to harvest sensitive player data.

“This is a hypothetical situation,” the World Economic Forum writes. “But the science of using movements tracked in VR to predict dementia, and the technology to do so, are very real. Currently, there are no standards or regulations as to how this data is collected, used or shared.”

All editions of the Meta Quest headsets include microphones and cameras. These features help bring VR to life, but they also enable a lot of data collection.

Data collected by the Quest headsets can include voice recordings or background sounds in your home. As the privacy notice says: “Depending on where you use Voice Commands, the microphone may pick up other sounds in the immediate area beyond your voice – including ambient noise or nearby background conversations.”

Read: How to read a privacy policy

The Quest 3 in particular can gather lots of visual data. This newest version is designed for better mixed reality use – meaning it overlays a virtual element onto your physical space, like showing an alien sitting on your couch. To do this, the headset needs to gather data like the dimensions of your room and the placement of your furniture. If misused, that information can communicate a lot about your family such as where you shop and how much money your family has.

The Meta Quest 3 headset has 6 external facing cameras, 4 of which you can see here.Photo by PIRG staff | TPIN

Quest’s cameras and sensors gather movement data about you, like your headset’s position and orientation and how you move the hand controllers. This allows it to simulate your movements virtually, translating your actual body movements to allow your avatar to move the same way in the virtual world.

With just a few minutes of movement data collected through a VR escape room game, researchers could infer a player’s age, relative physical fitness level and geolocation.

Movement data can be very revealing. For example, researchers in a 2023 UC Berkeley study were able to identify a single person out of a database of more than 50,000 people, with 94% accuracy, using only 100 seconds of an individual’s head and hand motion data collected using Meta’s VR game Beat Saber. The study concludes that using VR motion data could identify people as accurately as fingerprints do.

A different 2023 UC Berkeley study found that with just a few minutes of a movement data collected through a VR escape room game, researchers could infer a player’s geolocation, their age, relative physical fitness level and physical or mental disabilities. As the researchers point out, malicious actors could easily set up an innocent looking VR game to harvest data. Because of the immersiveness of VR games, it would also be easy for a game’s design to encourage players to take certain actions in order to gather better data about, say, their reaction time or size of the player’s room.

With little to no regulation around how companies can collect and use biometric and movement data, parents may want to be aware of the sensitivity of VR-generated data before bringing a system home. PIRG is working to get better protections on the books.

Apps on your phone or tablet are notorious for collecting lots of unnecessary data, including data about children. Apps available in Meta’s VR app store can collect a lot, too.

For example, the free and popular VR app Rec Room, which we tested, states in its privacy policy it may collect “your first, middle and last name, email address, username, mailing address, Social Security number or employer identification number, telephone number, IP address, or display name” among other things.

In order to know what a VR app is gathering on you or your child, you need to review its privacy policy – and each app will have its own fine print. Each app will also likely have its own settings which may default to gathering more information than is really necessary. You’ll want to check the settings on every app your child uses.

Read: How to read a smart toy’s privacy policy

Whenever apps gather excessive information from us and sell or share it with other companies, it increases the odds our data will be exposed in a breach or a hack and end up in the wrong hands. This can pose immediate safety concerns if your child’s location data is exposed. It can also increase the odds your family will be the victim of scams, fraud or identity theft if information like email addresses, birthdates or voice recordings get leaked. With more sophisticated ‘deepfake’ voice scams on the rise, companies collecting, storing and using voice data is only getting more dangerous.

Some apps allow users to take screenshots and recordings of virtual spaces and save them to their account for private viewing or later sharing. This means your avatar and voice may appear in other people’s screenshots or recordings.

This is true even if you have the highest privacy settings, and is true even for the youngest children’s accounts, for ages 10 – 12.

VR headsets offer immersive entertainment that many may find engrossing and fun.

The experts we spoke to recommend you avoid allowing your child to have a Meta Quest VR headset – or any other headset brand – this holiday season. The technology is in its very early days and there’s a lot of research to be done proving VR is safe for developing brains.

If you’re thinking of getting a VR system for your home, here’s what questions to ask and steps to take to ensure a safer experience.

Right now, there are no rules stopping tech companies from monetizing the data of kids and teens.

Sign the petition

Using the time-tested tools of investigative research, media exposés, grassroots organizing, advocacy and litigation, MASSPIRG Education Fund, a 501(c)(3) organization, stands up to powerful interests and delivers concrete results. But we need your support to keep our work going strong.

As threats to the public interest grow, our work becomes more important every day. Every contribution powers our research, fuels our advocacy, and sustains our future.

R.J. focuses on data privacy issues and the commercialization of personal data in the digital age. Her work ranges from consumer harms like scams and data breaches, to manipulative targeted advertising, to keeping kids safe online. In her work at Frontier Group, she has authored research reports on government transparency, predatory auto lending and consumer debt. Her work has appeared in WIRED magazine, CBS Mornings and USA Today, among other outlets. When she’s not protecting the public interest, she is an avid reader, fiction writer and birder.

Master's Policy Research Intern

Report ●