“You might want to tell your instructors about this:” students as sales reps?

In the wake of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, the education community has worried about how student personal and behavioral data gathered from access codes will be (mis)used for. Here's one example.

By Kaitlyn Vitez (USPIRG) with support from Billy Meinke (UH Manoa)

“It’s bad enough that I have to pay to do my homework. I don’t want to be used to force other students to have to do this too.”

When Lauren Kalo bought her materials for classes this semester at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, she thought it was a one way transaction. This past January, she spent nearly $700 on textbooks and access codes, including a $105 access code from Cengage for her microeconomics class. In the process, Lauren signed an end-user license agreement (EULA) that gave the publisher the right to collect a host of personal and behavioral information. She wasn’t expecting that checked box to make her an unofficial spokesperson for the company.

In the wake of the Cambridge Analytica scandal over misuse of information gathered on Facebook, the education community has turned its attention to its own issues with transparency of data collection and use. Advocates of open textbooks question what this data will be used for, and worry that publishers have more access to this data than they should.

We now know one use of this data. And it’s pretty Orwellian. Some textbook publishers are flagrantly misusing this data to pressure students into promoting new products.

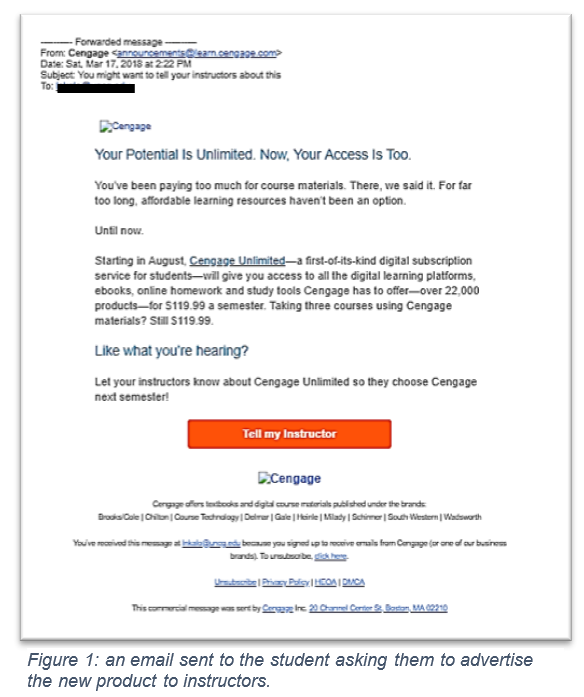

Last month, Lauren received an email from Cengage asking her to share information with her professors about Cengage’s new Unlimited model, where students would pay a flat fee for access to up to six courses’ materials.

“They’ve sent me a couple emails about tech stuff and receipts. But I definitely didn’t sign up for this,” she said.

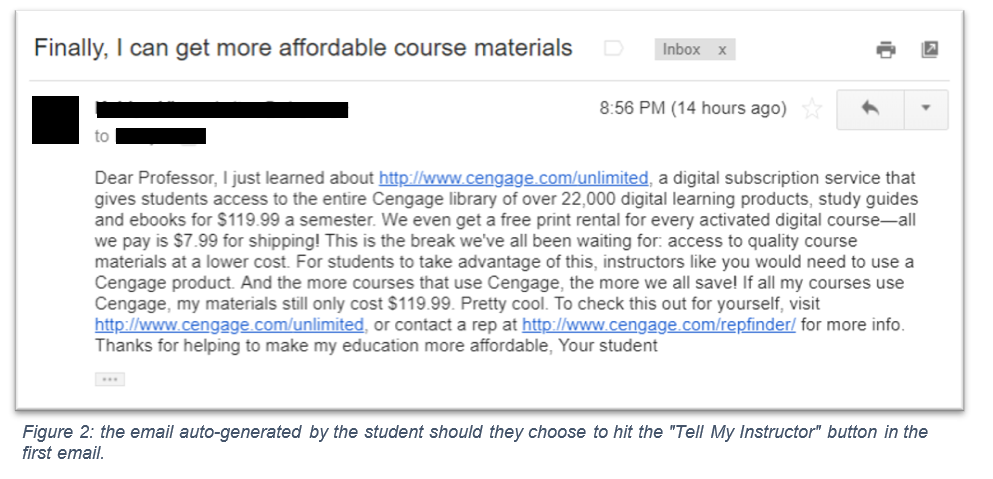

It was spam, plain and simple. If Lauren hit the “Tell My Instructor” button, Cengage would pop out an email, asking her to add her professor’s email address in. Students also receive these messages within the platform, mixing homework reminder messages with promotional content.

This particular use of a student’s information is ripe for abuse by the publisher and fundamentally changes the relationship between the student and faculty member in an unhealthy way.

This marketing push goes beyond digital targeting. Some of the biggest publishers, such as Cengage and Pearson, are hiring students to do in-person promotional work as well. Students are paid to do drop-in meetings or educational events with professors to pitch new products, to distribute posters and other materials on campus, or to submit op-eds to campus papers.

Students already are aware that they don’t have free will in the textbook marketplace- they must purchase the materials that their instructors assign. This canned email generated by Cengage isn’t the voice of students reclaiming their right to more affordable textbook options. It is a move by powerful special interests to co-opt the voices of students to support their own bottom line.

And here’s a scary question for further research. What else could these giant textbook companies do with unfettered access to and use of students’ data?

The bottom line is that students like Lauren are fed up with companies misusing their level of access to individuals and their information to make even more money off of students.

She lamented, “It’s pretty agressive, I don’t like how they’re using us to get into the professor’s head. The worst part is that professors could totally fall for it.”

Topics

Authors

Find Out More

Apple AirPods are designed to die: Here’s what you should know

New report reveals widespread presence of plastic chemicals in our food

FTC goes after second tax prep firm, H&R BLOCK joins INTUIT TURBOTAX for deceptive claims of “Free tax prep”