How printers keep us hooked on expensive ink

Manufacturers lock us into buying ink cartridges at exorbitant prices. There are simple steps to end the ink trap.

Printer ink is sold at an absurd markup. Black printer ink purchased wholesale costs $1.18 per fl. oz., while functionally the same ink in a cartridge costs $118 per fl. oz.*

The black printer ink found wholesale on the left costs 100-times as much as the retail black ink cartridge on the right.Photo by staff | TPIN

Martin Shkreli became a public pariah when he marked up Daraprim by 5,000%. Meanwhile, printer manufacturers regularly markup ink by some 10,000%. We shouldn’t tolerate price gouging on medication, nor should we turn a blind eye to the practice for other products.

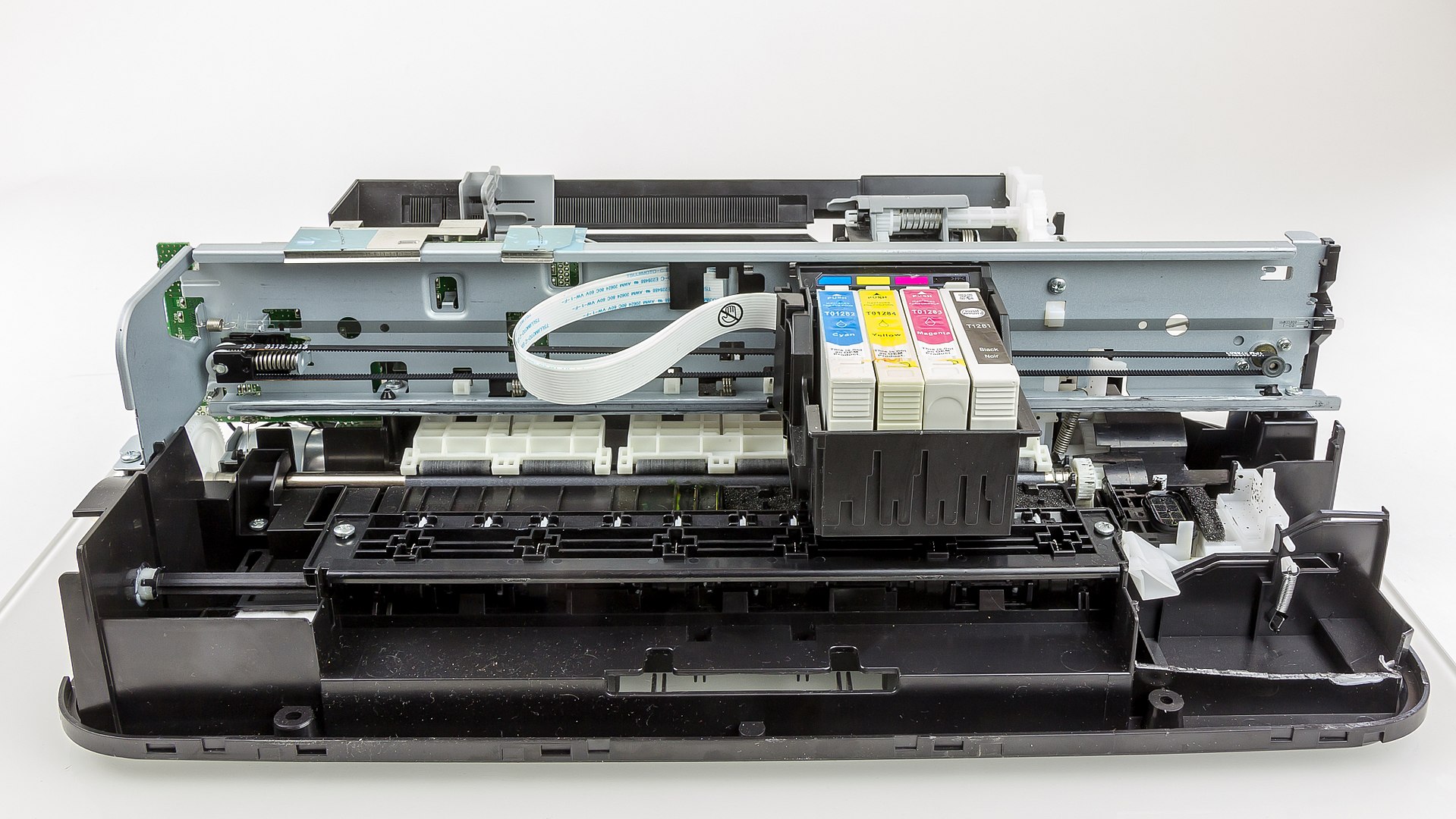

How can the ink in a name-brand cartridge cost 100-times as much as the same ink in a bottle? Manufacturers have designed an elaborate markup racket using anti-choice technology to cajole, push, and even force us into paying exorbitant prices for ink.

For example, manufacturers design printers that reject cheaper third-party ink cartridges. These software locks push us to buy their name-brand expensive ink. As a result of these schemes, ink cartridges waste our money and become another unsustainable single-use plastic product.

We shouldn’t have to pay so much for ink. I recommend three ways to restore transparency and choice to the marketplace.

$21 billion in ink sales

You might question if home printers are relevant, but 47% of American households still have one and our country spends more than $21 billion on ink cartridges per year.*

I’ve calculated that Americans could save $10 billion per year by using refilled ink cartridges.* Refilling rather than manufacturing single-use plastic cartridges could save the plastic equivalent to 4 million single-use plastic grocery bags per year.* Unfortunately, we can’t choose refilled or third-party cartridges if our printers’ software pushes us into buying expensive name-brand ink.

Printers are the poster child for software locks

Software which favors proprietary ink cartridges forces us into a cycle of replacement when there are cheaper and more environmentally-friendly options available.

Printers aren’t alone in their use of software to steer product owners to purchase more from the manufacturer. It’s increasingly common for manufacturers to restrict how we use products with software locks. iPhones restrict repair, Teslas won’t accept some third-party accessories, and tractors stop farmers from a set of DIY fixes. Printer restrictions are the poster child for the growing conflict between common-sense ideas of ownership and restrictive copyright claims.

We need the government to regulate these unfair business practices. Policy that protects choice could save Americans billions of dollars and lessen the impact of technology on our environment. We should protect our fundamental freedom to own what we’ve paid for.

I share three recommendations that can fix printers and address this major fault line in the American economy. The marketplace is full of cheaper and less wasteful products that are difficult to access because companies use software to restrict our choices. If we can fix printers, maybe we can fix the disposability treadmill that pushes us to replace working technology. We can have products that are designed to last, fixable, and don’t rely on a business model of extorting us for revenue extraction.

Why manufacturers restrict ink choice

Printer manufacturers operate on a “razor-and-blades” business model, meaning they make their money on sales of disposable cartridges with consumable ink. They sell printers at a loss to get consumers locked into expensive name-brand ink cartridges.

Once we’ve taken the bait, manufacturers sell their ink for a much higher cost than a competitive market would allow. To keep making money, manufacturers need to stop us from filling our printers with our own choice of ink. They push, prod, and even force us to buy their expensive ink when there are cheaper and more environmentally-friendly options available.

How printers keep us dependent on expensive ink

1) They program the printer to accept only name-brand cartridges

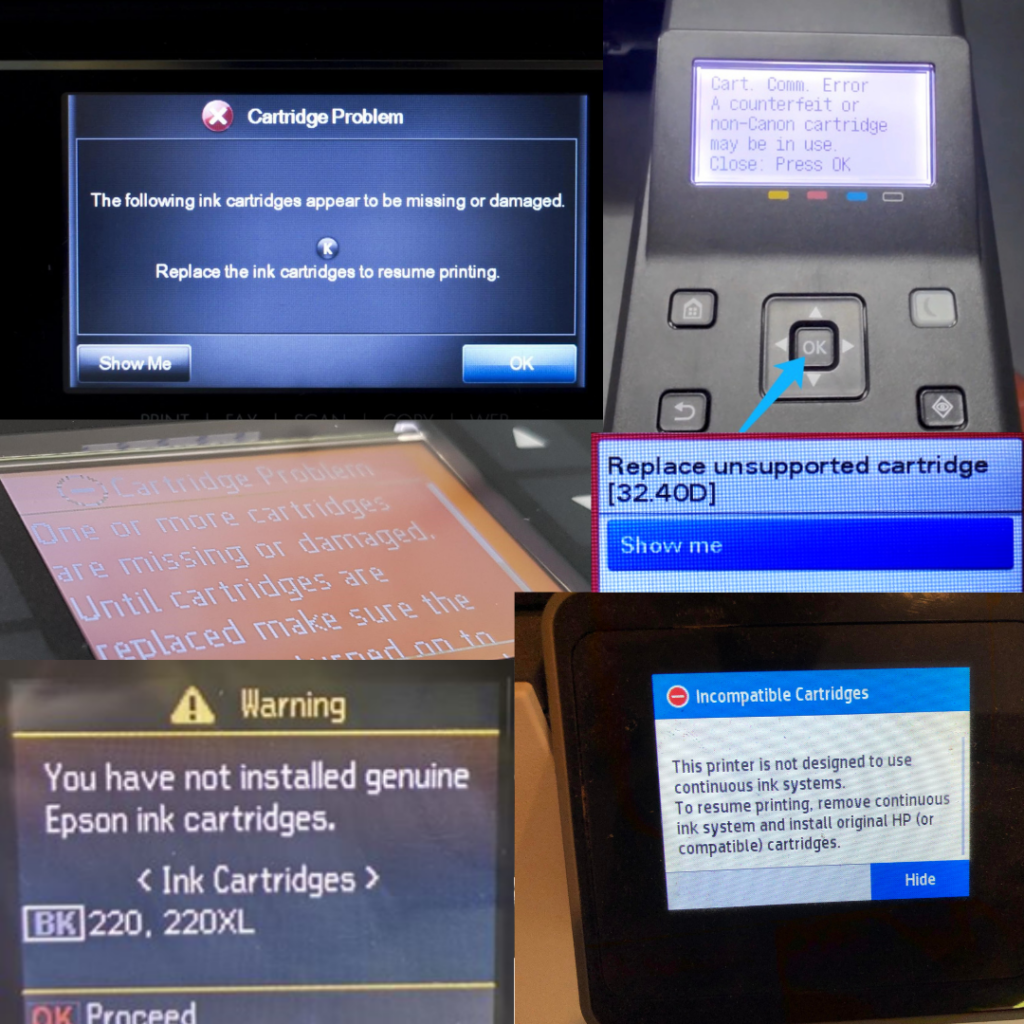

Manufacturers put computer chips on their cartridges. If the printer doesn’t detect that proprietary chip, it then can discourage or block users from using third-party ink.

Photo by staff | TPIN

Manufacturers often claim these restrictions are for “security.” I couldn’t find any example of criminals causing damage by using third-party ink cartridges, nor does that seem plausible. If a company is restricting how we use products we’ve purchased, the burden of evidence should be on the manufacturer to prove the necessity of these restrictions. Especially when, historically, manufacturer mistakes, and not third-party ink, have been the causes of security issues.

These companies’ own actions call into question their security claims. During the pandemic when supply chain disruptions prevented easy access to the computer chips needed to restrict third-party ink cartridges, Canon sold their own ink without chips and told consumers it was fine to ignore warnings.

Photo by Reddit | Public Domain

2) They block features to push us to buy unnecessary ink

Many of our home printers are also scanners and copiers, often marketed as “all-in-one.” We all know that ink is required for printing and making copies, but manufacturers have gotten in hot water for restricting access to scanning when ink is low. Why would ink be needed to scan documents if not only because it helps manufacturers make a quick buck?

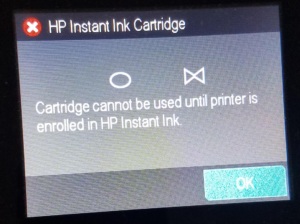

HP and Epson both had ink subscription services that claim to help us save money and the hassle of remembering to buy more when we’re running low. This is convenient for many consumers until they hit a snag.

Error. Printer owners were confronted with an error message because, through no fault of their own, Epson was unable to process their payment for their ink subscription service ReadyPrint. These payment issues resulted in Epson remotely disabling the printers and ink that users already owned. HP users have similarly been met with remotely disabled printers when they stopped their Instant Ink subscription.

Photo by Geek Street | Public Domain

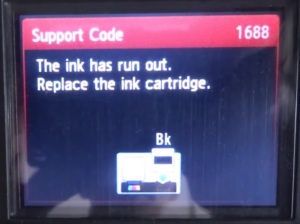

3) Premature low ink warnings

Epson was sued for allegedly indicating that cartridges were low on ink far before, according to plaintiffs, it was necessarily true. Users say they were met with an error that wouldn’t allow them to print due to “low ink level” warnings—although they claim there was plenty of ink left to use. A PCWorld investigation found that weighing dead cartridges revealed “some left more than 40 percent of their ink unused.”

The upshot is that “low ink” doesn’t mean the cartridge is out of ink. There could be hundreds of pages left to print, or just two. These vague warnings encourage us to buy more ink that we might not need.

4) Designed to waste

According to testing by Consumer Reports, “with many printers, more than half of the ink you buy will never wind up on a page.” Many printers are very inefficient and even wasteful with the pricey ink we’ve bought with our hard-earned cash.

Printers don’t just use ink for documents and images, they also clean their printheads with ink. This maintenance is necessary but the inefficiency of ink used isn’t. There are large disparities in the amount of ink used for printhead cleaning among different models and brands. That means companies could invest in efficiency if they chose.

We need printer ink freedom

We should be able use whichever ink cartridges we choose for our printers. For example, some companies recycle empty cartridges by refilling them with ink. If we choose, we should be able to refill the cartridges in our printer with competitively priced ink rather than be pushed to pay a premium to manufacturers.

Using refilled cartridges is a good deal for our wallet and our planet. Americans could save $10 billion per year by using refilled ink cartridges. We could save the plastic equivalent to 4 million single-use plastic grocery bags per year.* That’s because it takes plastic to produce the body that holds ink in single-use cartridges.

After the materials needed to make these cartridges have been extracted, the carbon needed to produce them has been emitted, and we’ve used up the ink to print our return labels, the vast majority of used cartridges end up in landfills. These cartridges join the growing electronic waste stream, which in 2021 weighed more than the Great Wall of China. Reusing these cartridges and refilling them with new ink can reduce the carbon emissions needed to produce them by between 33% and 61%.*

Photo by Anonymous | Public Domain

Why can’t I refill my printer ink cartridges?

Major printer manufacturers such as Epson, HP, and Canon have tried to block cartridge refilling using software restrictions and their market power. Consumers once were able to refill cartridges themselves at Office Max, Walgreens, Costco and other retail stores—now it’s increasingly rare to find. Aftermarket cartridge expert Aaron Leon believes these services became unviable due to the software restrictions and complicated encrypted computer chips manufacturers have installed on cartridges.

HP reportedly promised heavy incentives to retailers who would stop selling refilled cartridges.. HP and Canon have also had Amazon remove hundreds of listings for third-party ink claiming the products violated the companies’ intellectual property”. As of writing, Staples sells refilled ink cartridges, but consumers can’t refill used cartridges.

While ink cartridges seem to have had little innovation in decades, manufacturers have developed inventive legal arguments to stop cartridge refilling. Lexmark sued a third-party cartridge chip manufacturer for infringing their copyright and claimed consumers were bound by an agreement not to resell cartridges because they opened packaging with the terms printed on it. In 2017, the Supreme Court ruled 7-1 against the printer manufacturer. The court’s decision affirmed “patent exhaustion” which, “prevents patent owners from controlling goods after sale and interfering with your right to resell, tinker with, and understand the things you own.” This ruling was a win for consumers.