Reaping What We Sow

How the Practices of Industrial Agriculture Put Our Health and Environment at Risk

Shaped by modern technologies, financial influences and public policy, American agriculture has evolved into an efficient system that produces all the food the country needs and more. However, in addition to the benefits that our food system offers, the shift to larger and more specialized farms has damaged public health and the environment. This damage is avoidable. Now is the time to reform agricultural practices to better protect public health, the environment, and our future ability to grow food.

Downloads

Shaped by modern technologies, financial influences and public policy, American agriculture has evolved into an efficient system that produces all the food the country needs and more. However, in addition to the benefits that our food system offers, the shift to larger and more specialized farms has damaged public health and the environment.

Raising thousands of animals in confined spaces encourages the misuse of antibiotics that leads to antibiotic-resistant infections in people. Policies and financial systems that prioritize industrial-scale production of corn and soybeans lead to the loss of topsoil and depletion of aquifers, imperiling the longterm productivity of the nation’s agricultural lands.

Such damage is avoidable. The adoption of farming practices that focus not just on shortterm production but also consider the broader environmental and health consequences of agriculture can enable America to continue producing abundant food. Consumers are expressing increasing preference for food produced sustainably. Now is the time to reform agricultural practices to better protect public health, the environment, and our future ability to grow food.

Farms Have Become Larger and More Specialized

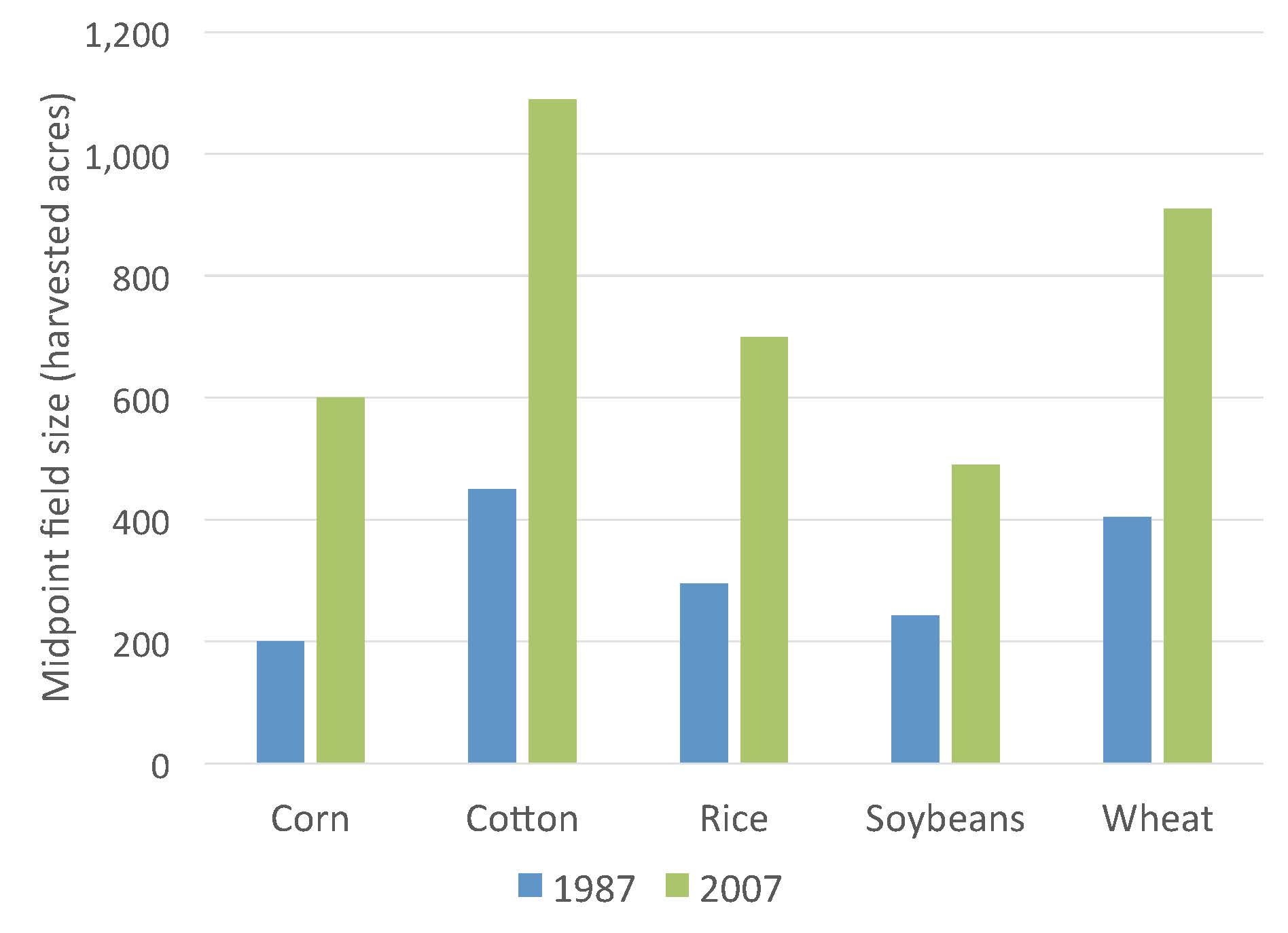

Industrial farms have grown larger. Commodity crops like corn, cotton and soybeans are grown on bigger fields than ever before. For example, the midpoint size of a corn field – the size at which half of all acres of corn exist on smaller fields and half exist on bigger fields – tripled to 600 acres from 1987 to 2007. (Figure ES-1 shows midpoint field size for several commodity crops.)

Figure ES-1. Field Sizes for Common Crops Increased from 1987 to 2007

Similarly, livestock are being raised in increasingly larger herds and flocks using practices that harm the health of humans and animals. In 1987, half of all hogs were raised on farms with at least 1,200 hogs, but by 2007 this midpoint increased 24-fold to 30,000 hogs.

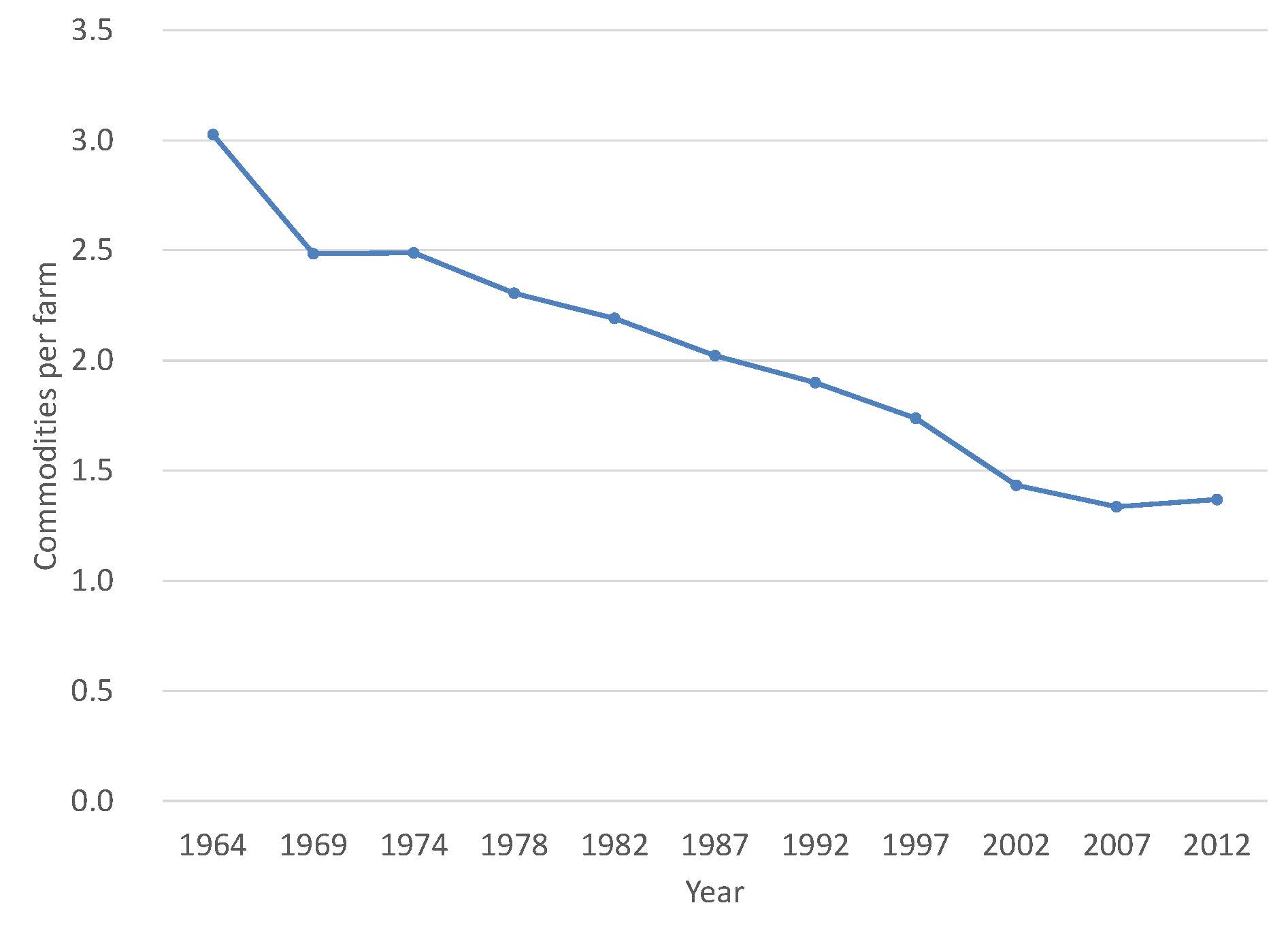

At the same time as farm size has increased, variety has decreased. Whereas in 1964, the average farm produced three different products – growing multiple crops, raising different animal species, or a combination of both – today’s farms produce on average only slightly more than one product. (See Figure ES-2.)

Figure ES-2. Farms Have Become More Specialized (Average Number of Commodities – Crop or Livestock – Produced per Farm since 1964)

Our Agricultural System Produces More Food than We Can Consume

The nation’s agricultural system now produces more food than we can consume or than is good for us. For example, we have access to two and a half times as much meat, fish, eggs and nuts as nutritionists think we should eat. Similarly, even though Americans, on average, consume far more sugar, fats and oils than recommended by nutritionists, national availability of these nutrients far outpaces what we actually consume.

Larger and More Specialized Farms Harm Public Health and the Environment

In the course of producing this surplus of food, large, specialized farm operations contribute to a host of environmental and public health problems. The harmful impacts of industrial agriculture include:

- Loss of topsoil: Current farming practices are contributing to the loss of topsoil, the layer of ground that contains most organic matter and the nutrients necessary for plant growth. Topsoil has been eroding faster than it can be replaced, which threatens future crop yields.

- Water pollution: Applying too much fertilizer, whether manure or synthetic fertilizer, or applying fertilizer at the wrong time can pollute nearby waterbodies with nitrogen and phosphorus. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has repeatedly identified agriculture as the industry with the largest negative impact on water quality in U.S. rivers and lakes.

- Aquifer depletion: Roughly 80 percent of national water consumption is due to agriculture. This heavy use has led to aquifer depletion and water scarcity in some of the country’s main agricultural regions.

- Pesticide overuse: Heavy pesticide use harms people and the environment. Some of the most commonly used pesticides in the U.S. have been linked to cancer, autism and lower IQ. Farm workers and their families face a heightened risk. The overuse of herbicides has created herbicide-resistant weeds, which have infected 60 million acres of crops and will make future farming more difficult.

- Antibiotic-resistant disease: Factory farms often feed their animals daily doses of antibiotics. This routine antibiotic use contributes to the emergence of drug-resistant bacteria that can infect people with illnesses that are difficult and sometimes impossible to cure. The World Health Organization, the United Nations, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have declared antibiotic resistance one of the gravest threats facing public health.

- Obesity: More than one-third of the U.S. population is obese, a proportion that has increased by 65 percent over the last 30 years. This increased prevalence of obesity, and the related risk of diabetes, heart disease, stroke and other diseases, is tied to overconsumption of some of the main products of industrial agriculture.

- Climate change: Improper soil management, methane emissions from cattle, and the production and combustion of biofuels are all sources of agricultural greenhouse gas emissions. Even without accounting for biofuels, the EPA estimates that the agricultural sector was responsible for roughly 9 percent of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions in 2015.

Federal Policies Have Helped Shape the Damaging Production Patterns Seen in Today’s Larger and More Specialized Farms

Federal farm policies, such as the long-running direct payment program, have encouraged the transition to industrial farming and its damaging approach to production. Technological advances, bank lending that favors large farm operations, and other forces have also shaped modern agriculture. In 2014, the federal direct payment program was ended, but crop insurance has started to play a similar role in supporting harmful farming practices.

Crop insurance incentivizes farms to specialize and produce the same few crops. Farmers who grow one or two commodity crops like corn and soybeans have more insurance options than farmers who grow fruits and vegetables. In addition, farms with multiple crops often need to insure each variety separately, a time-consuming process that makes large single-crop fields more economically viable than more diverse farms.

Other federal policies also encourage practices that damage public health and the environment. For example, programs that provide funding to farms that invest in conservation measures have given the most grants to concentrated animal feeding operations to build additional manure storage facilities. While some of these investments, such as anaerobic digesters, can be important for reducing global warming pollution, this funding also provides an incentive to farmers to continue raising huge, single-species herds rather than addressing the root of the problem by reducing herd size. Additionally, the federal Renewable Fuel Standard has encouraged the conversion of environmentally vulnerable land into cornfields.

America produces much more food than we need to live healthy lives. That abundance creates the opportunity to rethink the nation’s agricultural policies in order to protect our environment, our health, and our ability to produce food sustainably for generations to come. By shifting key public policies, we can change how our food system operates, and better protect public health and the environment. Necessary changes include:

- Reforming crop insurance and renewable fuel programs to end excessive production of commodity crops and discourage planting on unsuitable land.

- Requiring farms to adopt sustainable practices in order to receive federal funding, and put effort into ensuring that farms continue to comply.

- Increasing support for crop diversification, which returns nutrients to the soil and disrupts pest cycles.

- Ending the routine use of antibiotics in food-producing animals.

- Changing incentives to help farmers address the cause of excess manure production from factory farms, rather than just funding manure storage facilities or anaerobic digesters that deal with the consequences of the problem.

- Holding industrial farms accountable for polluting our water supply.

- Increasing policy support for sustainable agricultural practices, such as organic production that consumers have increasingly indicated they prefer.

Topics

Find Out More

Food for Thought Part 2: An analysis of food recalls for 2022

Out to Pasture