The titans of “Main Street”: Mission creep in a key Fed rescue program threatens public trust

At this critical moment, it is particularly important that the actions of the Fed, the Treasury and all government agencies match their words. Making corporate titans eligible for “Main Street” financing falls short of that standard.

When politicians talk about “Main Street” businesses, I picture the shops on our local main drag, Dorchester Avenue in Boston. I think of the just-opened restaurant run by a man who has overcome hardship, missteps and tremendous odds to finally see his dream of a kitchen of his own come true. I think of the local bike shop, the cafe with the tasty muffins, and the myriad small pharmacies, grocers and stores in our neighborhood’s “Little Saigon.”

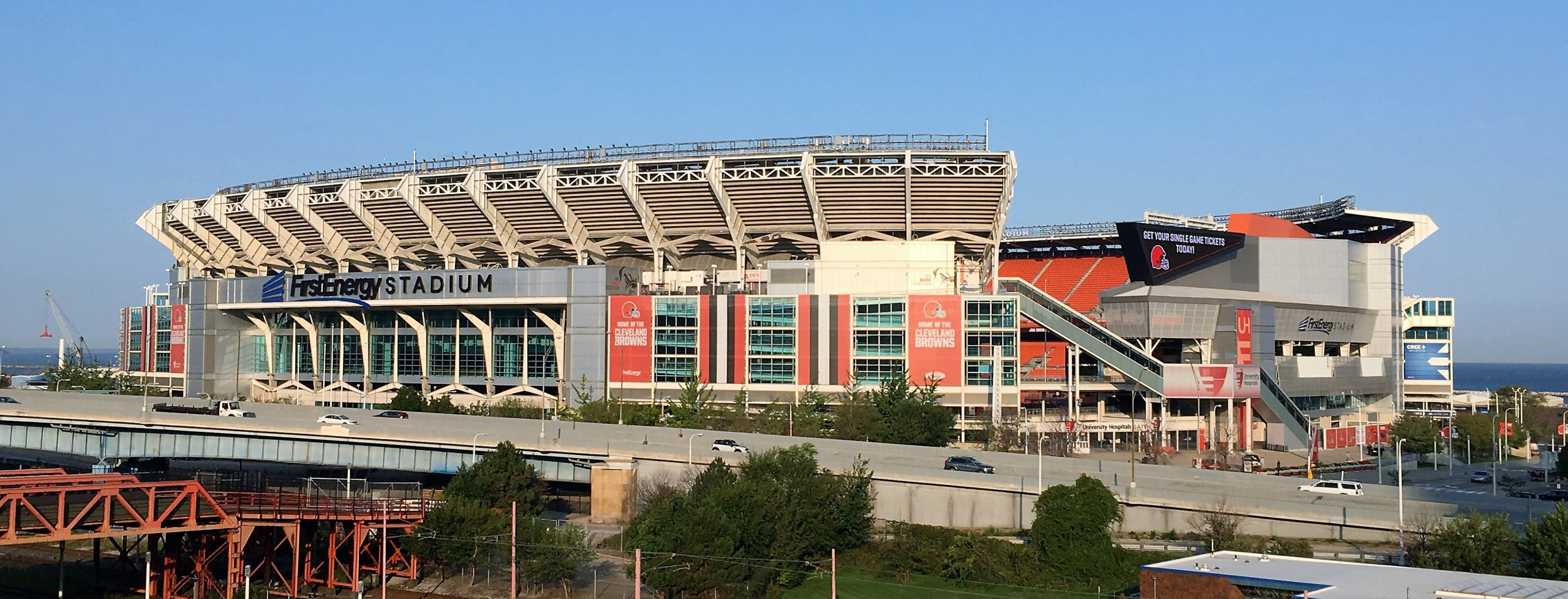

I don’t think of Fortune 1000 companies. And I sure don’t think about corporations with their names on football stadiums. Yet, these are exactly the kinds of businesses now eligible to take part in the Federal Reserve’s new Main Street lending program.

The Main Street program made headlines recently during the debate about bailouts to the oil and gas industry. Desperate for credit, oil and gas firms and their supporters in Congress beseeched the Trump administration and the Federal Reserve to tweak the rules of its emergency lending programs to allow more oil and gas companies to take part – just one of many recent attempts to rescue the industry from its own self-inflicted financial woes.

Two weeks ago, the Federal Reserve did exactly that. Among other changes, the Fed lifted the cap on the number of workers that could be employed by a company receiving Main Street loans from 10,000 to 15,000, and on the annual maximum revenues of those companies from $2.5 billion to $5 billion.

Missing in the media coverage of the shift was the following question: What kind of “Main Street” businesses employ 15,000 people or pull in $5 billion per year?

To find the answer, I looked in that compendium of knowledge and information on American small business: the Fortune 1000. The index ranks the top 1,000 American businesses by total revenue. And while there are other conditions to the Fed program that would likely render some of those businesses ineligible, when measured by size alone, most would qualify as “Main Street” businesses for the purposes of the Fed program.

Of the 1,000 companies in the index, 461 report revenues at or below $5 billion per year. Meanwhile, 563 of the Fortune 1000 reported having 15,000 employees or fewer. And of those businesses with more than 15,000 employees, 89 have less than $5 billion in annual revenues.

Nearly two-thirds of the Fortune 1000 – 652 businesses – would therefore qualify as “Main Street” businesses eligible for assistance based on their annual revenue and number of employees.

Who are some of these mom and pop businesses struggling to get by?

Oil and gas firms are well represented, led by ConocoPhillips (#86 on the Fortune 1000) and Occidental Petroleum (#167), both of which now meet the criteria for Main Street financing due to the Fed’s rule changes two weeks ago. Also newly eligible are two Fortune 100 oil refiners: Phillips 66 (#23) and Valero (#24).

At least three corporations whose names adorn major league sports venues also now meet the new size criteria, including utilities FirstEnergy (#263, FirstEnergy Stadium, home of the Cleveland Browns) and Xcel Energy (#274, Xcel Energy Center, home of the Minnesota Wild hockey team), as well as Raymond James Financial (#407, Raymond James Stadium, home of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers).

It is unclear whether any of the companies named above will apply for loans from the Fed or meet the central bank’s other eligibility criteria for the Main Street program (though the tenacity of the lobbying push by oil-state senators suggests that troubled fracking firms very well might.) And one might argue that the disruption caused by COVID-19 requires a strong Fed response – even on behalf of the nation’s largest firms.

But the rejiggering of eligibility criteria for the Main Street program is just one more example of mission creep for programs established early in the pandemic that were supposed to be intended for small businesses.

Indeed, when the CARES Act was enacted, the focus of press coverage was on the $1,200 checks going to American households, help for small businesses, assistance for the health system, and bailouts for industries like airlines, with a portion of the funding helping to rescue larger firms. The fact that a share of the funds in the law would enable as much as $4 trillion in lending and corporate bond purchases by the Federal Reserve was little appreciated at the time.

Adding to the confusion was the Fed’s own rhetoric surrounding its creation of the “Main Street” lending program, which it had initially billed in a March 23 announcement as supporting “lending to eligible small-and-medium sized businesses, complementing efforts by the [Small Business Administration].”

The media continued to describe the program as intended to “facilitate lending to small businesses” even after, on April 9, the Fed stated that the program would offer loans to “companies employing up to 10,000 workers or with revenues of less than $2.5 billion,” a category that includes a significant number of Fortune 1000 firms.

By the time of the most recent revision, the central bank had not only raised the cap on the number of employees and annual revenue for potential participants, but it had also allowed for individual loans of up to $200 million (up from $150 million in the original program).

Why does any of this matter?

Substantively, it could matter if demand for loans by true small and mid-sized businesses is crowded out by demand from larger enterprises. The Fed appears to have plenty of resources to throw at that problem if it chooses, but the speed with which the small business-focused Paycheck Protection Program was oversubscribed serves as a warning.

There is also the risk that some of the new, larger risks taken on under this program will not turn out well, exposing taxpayers to potential losses. That’s particularly possible with loans made to oil and gas firms, which were on shaky financial ground even before the crisis.

But the biggest worry is that mislabeling a corporate loan program open to nearly two-thirds of the Fortune 1000 as a “Main Street” program will further erode Americans’ trust in the stewardship of the COVID-19 economic rescue. Revelations of large, publicly-traded companies receiving payouts under the Paycheck Protection Program have already put a dent in that trust, as has President Trump’s dismissal of key watchdogs empowered to supervise the government’s bailout activities.

Recovering from COVID-19 and building a better country afterward will require unity. And unity requires trust.

If trust is to be built and maintained, those who design our nation’s economic response need to treat words as though they matter – and to prioritize assistance to the places where Americans can agree that help is most needed and most beneficial. Trust also demands transparency – a willingness to empower the public, which is being asked to bankroll the investment in business recovery, to see in real time where their money is being spent. While the Federal Reserve has taken important steps to ensure transparency in its emergency facilities, the sheer size and speed of the economic rescue demands that information be shared openly with the public and that the rationale behind important decisions be fully explained.

At this critical moment, it is particularly important that the actions of the Fed, the Treasury and all government agencies match their words. Making corporate titans eligible for “Main Street” financing falls short of that standard.

Photo: FirstEnergy Stadium, home of the Cleveland Browns. Credit; Erik Drost, CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Authors

Tony Dutzik

Associate Director and Senior Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Tony Dutzik is associate director and senior policy analyst with Frontier Group. His research and ideas on climate, energy and transportation policy have helped shape public policy debates across the U.S., and have earned coverage in media outlets from the New York Times to National Public Radio. A former journalist, Tony lives and works in Boston.