Cars are lasting longer than ever. Will that change with new technologies?

Today’s high-tech cars rely on software and a slew of sensors. With more things to break or become obsolete, will new cars still last as long?

For decades, new cars in the U.S. have been increasingly durable, allowing them to remain in operation longer. But there’s a danger that trend might reverse if the growing use of electronics in cars, coupled with restrictive repair policies by automakers, makes it more expensive to undertake simple repairs or if long-term support is not available for the technology integrated into new cars.

Having to replace cars more frequently would be a financial blow to consumers and add to the environmental damage caused by cars. Design and support decisions by manufacturers, however, can help make sure that that doesn’t happen.

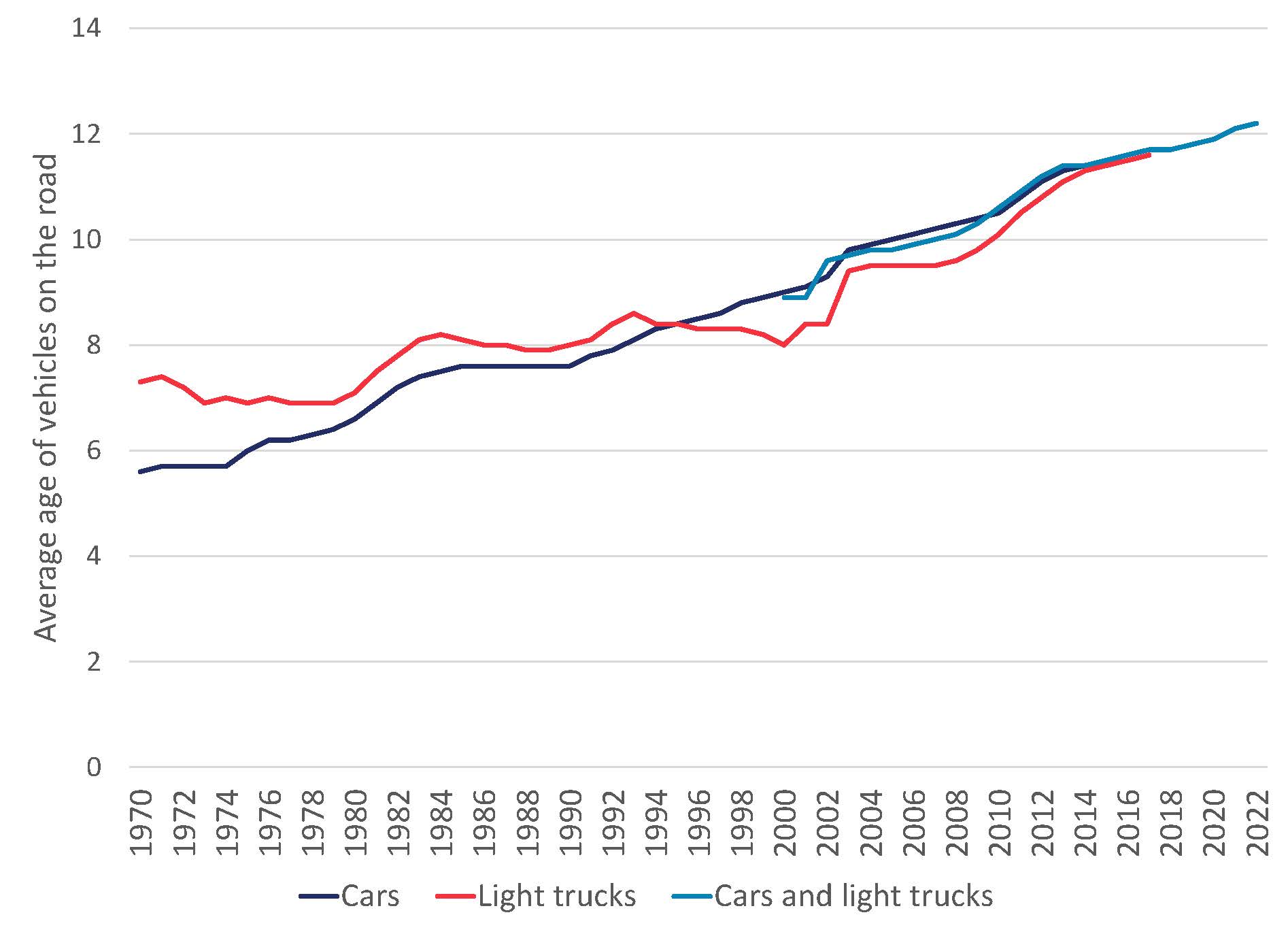

The average car or light truck on the road in 2022 in the U.S. was more than 12 years old. That’s the highest it has ever been. In 1970, the average car was only 5.6 years old and the average light truck was 7.3 years old. As the quality of new cars and trucks increased and as consumers’ expectations for vehicle longevity changed, drivers have kept them in operation for more years.

Over the decades, cars have become less vulnerable to rust and corrosion. Parts are now machined with greater precision and lubricants are more durable, reducing wear and tear. Even exterior paint fades less, interior fabrics and materials better withstand normal use, and headlights last longer. Manufacturers are so confident in the durability of critical components in vehicles that they now offer longer warranties than they did in the past. As a result, the average age of cars and light trucks on the road has increased dramatically.

Figure 1. The average age of cars and light trucks has increased over the decades

Photo by Staff | TPIN

Sources: Office of Highway Policy Information, Federal Highway Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation, “Average Age of Automobiles and Trucks in Use, 1970-1999,” updated May 31, 2022; and Bureau of Transportation Statistics, U.S. Department of Transportation, “Average Age of Automobiles and Trucks in Operation in the United States,” accessed November 15, 2023.

While improvements in automobile technology over the last half-century have led to ever-increasing lifespans, recent technological advances coupled with manufacturer policies may soon stall or even reverse this trend. The incorporation of more electronics into vehicles enables automakers to restrict aspects of the repair process and increases the odds that some vehicle components will become prematurely obsolete.

Copyright restrictions may raise repair costs

Many of the technologies in new cars that make life easier for drivers and safer for passengers increase the complexity of any needed repairs. Not only are replacement parts bristling with sensors, but they also need to be re-integrated into a vehicle’s electronic control system. Making matters even more complex, some carmakers have begun to impose restrictions on who can access the software tools needed to complete such repairs. These factors raise the cost of repair — and more expensive repairs increase the odds that a vehicle will be sold for salvage or scrap instead of being repaired.

The integration of advanced technologies into vehicles can increase the complexity of even a basic repair. A windshield replacement on an older car, for example, involves simply installing new glass and may cost $300-$600. Replacing the windshield on a newer vehicle equipped with rain-sensing wipers, automatic braking, adaptive cruise control, heads-up displays and other advanced features that rely on sensors behind the windshield, however, can cost far more. These systems require precise sensors, and obtaining the right part and calibrating the sensors raises repair costs. Replacing this type of windshield may cost $1,000 or more.

Bumpers and other easily damaged vehicle parts may be similarly expensive to repair or replace due to the heavy integration of safety and driver assistance technology.

Adding to the cost of vehicle repair is the opposition of some carmakers to allowing repair facilities to access materials needed to successfully repair modern, software-dependent vehicles. This includes the firmware or software needed to reconnect replacement parts to the vehicle’s control system. For example, though technicians at a repair shop might have the skill to replace a high-tech bumper, automakers will not share all the tools or information needed to reprogram or calibrate that component so that it will work as the original did. Because software in cars is protected by copyright law, not simply patent law as is the case for specific car parts, automakers have more power to restrict access. Even if you can get compatible parts manufactured by a third party, copyrighted software is often needed to install that part into the car’s systems. By limiting access to this copyrighted information, automakers and their dealers are able to charge more for repairs, undermine competition on spare parts, or preempt repair entirely.

As high-tech cars age and lose value, the elevated cost of repairs may hasten the rate at which they are scrapped rather than repaired.

Here’s how that dynamic works: If an insurance company is asked to pay for a repair, it evaluates the cost of the repair versus the value of the car. It typically will pay for a repair that is no more costly than replacing the car and selling the damaged one for scrap. If the repair costs too much relative to the car’s value, then the insurance company saves money by declaring the vehicle a total loss and writing a check for the value of the vehicle.

A vehicle owner faced with an expensive out-of-pocket repair might make a similar calculation and choose to trade in the car. It might then be sold for scrap if that is more valuable than fixing and reselling the car.

Technological obsolescence, planned or otherwise

Another reason why the average age of cars and trucks may begin to decline is their reliance on electronic or technological components that may become obsolete or non-functional sooner than vehicles’ mechanical components, rendering otherwise functional vehicles inoperable or eliminating access to key systems.

A reader of a recent Washington Post article commented on their experience with a 2011 Nissan Leaf, in which changes to wireless technology standards eventually eliminated the reader’s access to some of the car’s features. The Nissan owner wrote: “I bought a[n] all electric Nissan LEAF in 2011 and enjoyed the (new at the time) interactive connected service that allowed remote access to charge and pre warm or cool the car. Turned out that the Nissan service was based on 2G cellular service so a couple years later I had to pay $200 to replace/upgrade to a 3G chipset in the LEAF to continue using Nissan’s remote access service…. Finally, Nissan (and AT&T) stopped supporting 3G cell service in 2021 so remote access no longer functions.”

In this case, the reader lost access to “nice-to-have” features, but in other vehicles a functioning wireless connection may be essential for maintaining the car’s safety or operability. For example, Kia and Hyundai have used wireless updates to make their vehicles more difficult to steal. In other vehicles, if a car’s infotainment system freezes up, causing the driver to lose access to climate settings and other key systems in the vehicle, a wireless update may be needed to restore access.

That’s not a problem if the updates are available, but automakers might not necessarily provide indefinite support and updates for older vehicles. Carmakers, much like cell phone and computer manufacturers, may end support for older products’ operating systems after a limited number of years. Apple, for example, repairs phones up to seven years after a model was sold and ends software updates to fix security flaws after roughly the same period. There’s also the risk that an automaker, or its software supplier, could go out of business and no longer be available to provide updates. While relatively few cell phones might still be in use after seven or eight years, a similar approach by a car manufacturer would cut into the useful life of many cars.

Long-lived cars are better for consumers and the environment

Americans collectively hold $1.58 trillion in auto loan debt, more than ever before, as they finance bigger and more expensive vehicles than in the past. Purchasing a new (or newer used) vehicle is a major financial outlay, usually second only to purchasing a new home. The average car loan, whether for a new or used car, is more than five and a half years long, meaning drivers may already be making a monthly loan repayment for close to half of a vehicle’s life. If more technologically advanced vehicles last fewer years, consumers will need to buy replacement vehicles more often and ultimately spend more money on transportation.

In addition to household cost savings, maintaining vehicle longevity can deliver environmental benefits, too. Obviously, the shorter the lifespan of a vehicle, the more new cars need to be made – and manufacturing a new car, whether it is powered by gasoline or electricity, is an energy-intensive process. Keeping vehicles on the road for fewer years means less work is extracted from the energy embodied in the vehicle.

Design and support decisions by manufacturers will heavily influence whether vehicle longevity in the U.S. continues to increase, or reverses. Automakers can design components to make it easier and less expensive to replace just one part. Tesla, for example, has acknowledged that design changes to vehicle bumpers can help to lower repair costs.

Manufacturers can also commit to providing long-term support for the high-tech aspects of their vehicles. Customers should be able to rely on technology in their vehicles to last as long as the mechanical components.

Decades of manufacturing and technological progress have enabled manufacturers to produce vehicles that operate reliably for many years. There’s no good reason that the next generation of advanced technology should change that.

Topics

Authors

Elizabeth Ridlington

Associate Director and Senior Policy Analyst, Frontier Group

Elizabeth Ridlington is associate director and senior policy analyst with Frontier Group. She focuses primarily on global warming, toxics, health care and clean vehicles, and has written dozens of reports on these and other subjects. Elizabeth graduated with honors from Harvard with a degree in government. She joined Frontier Group in 2002. She lives in Northern California with her son.

Nathan Proctor

Senior Director, Campaign for the Right to Repair, PIRG

Nathan leads U.S. PIRG’s Right to Repair campaign, working to pass legislation that will prevent companies from blocking consumers’ ability to fix their own electronics. Nathan lives in Arlington, Massachusetts, with his wife and two children.

Find Out More

Why Microsoft extended Windows 10 support for schools for $1

Why do we toss working devices?

6 surprising facts from the UN’s 2024 electronic waste report