Food for Thought 2024

More than 300 food products were recalled in 2023 as a dozen outbreaks sickened 1,100 and killed 6

VIEW THE PDF

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

On Oct. 15, 2023, two people in the United States became sick enough, likely with digestive problems, to seek medical care. Within a week, seven more people were ill. By the end of the month, about 70 more people got sick.

More than three weeks after the initial illnesses, they were traced to Salmonella in fresh cantaloupe. Salmonella bacteria generally live in human and animal intestines; we can get sick when germs from contaminated feces get into water and food.

A cantaloupe recall was issued Nov. 8 but it took until Nov. 17 before the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) announced the cases were all related and, ultimately, part of a massive outbreak careening across the country. As of mid- November, Salmonella infected 43 people in 15 states. From mid-November through early December, 11 more cantaloupe recalls were issued by various companies, some of which used them in fruit cups and medleys.

By Christmas, at least 407 people in 44 states had become ill. Of those, at least 158 were hospitalized and six people died. The products were sold from September through early December. The CDC announced the outbreak was over on Jan. 19, 2024.

Another major recall that also started in October is not over. And people who are affected may not realize it for years.

We’re talking about the cinnamon and cadmium poisoning outbreak linked to pouches of cinnamon applesauce. On Oct. 28, 2023, the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services contacted the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) about four children whose blood showed possible acute lead poisoning. North Carolina pointed to WanaBana Apple Cinnamon Fruit Purée pouches. While testing various applesauce pouches, the state found “extremely high concentrations of lead,” at levels 2,000 times greater than what is regarded as safe, the FDA. The cause: cinnamon processor in Ecuador.

WanaBana LLC announced the initial recall Oct. 30 and expanded it Nov. 9 to include various cinnamon applesauce pouches under the Wanabana, Schnucks and Weis brands.

As of March 22, the FDA reports 519 lead poisoning cases from 44 states, Washington and Puerto Rico. Among confirmed cases, the median age is 1 year. Children are more vulnerable to lead poisoning. It’s scary because most exhibit no immediate symptoms, but long term, affected children can exhibit learning difficulties and issues with behavior, low IQ, growth, speech and hearing.

The recalls associated with the contaminated cantaloupe and lead-tainted applesauce were among 313 food recall announcements issued in 2023 by the FDA and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA.)

Contaminated cantaloupe, onions and peaches killed people last year and a wide variety of foods made more than 1,100 people sick – that we know of. Officials often say the number of illnesses they tally are likely only a fraction of the true toll. Many people recover from food poisoning without medical attention or, even if they go to the doctor or urgent care, they’re not tested for a specific illness or the illness isn’t reportable.

All 12 of the cantaloupe recalls and both of the applesauce recalls were issued by the companies – not regulators, even though regulators uncovered the dangers in these foods. In fact, while the FDA, which regulates about 78% of the food we eat, technically has the authority to issue mandatory recalls for food, it almost never happens. The USDA has no mandatory recall authority.

In the 13 years since the Food Safety Modernization Act became law, the FDA has issued mandatory food recalls only three times; in 2013, 2014 and 2018.

All of this points to three big problems with food safety:

- Tracking down the source of food poisoning takes weeks, months or sometimes years.

- Once a problem food is identified, recalls often take too long to issue because regulators can’t mandate.

- When recalls are announced, consumers often don’t find out about them in a timely fashion, if ever.

U.S. PIRG Education Fund analyzed all 313 recall announcements issued in 2023 to examine why foods were recalled, what went wrong and what can be done to fix it. This report looks at what we found.

KEY FINDINGS

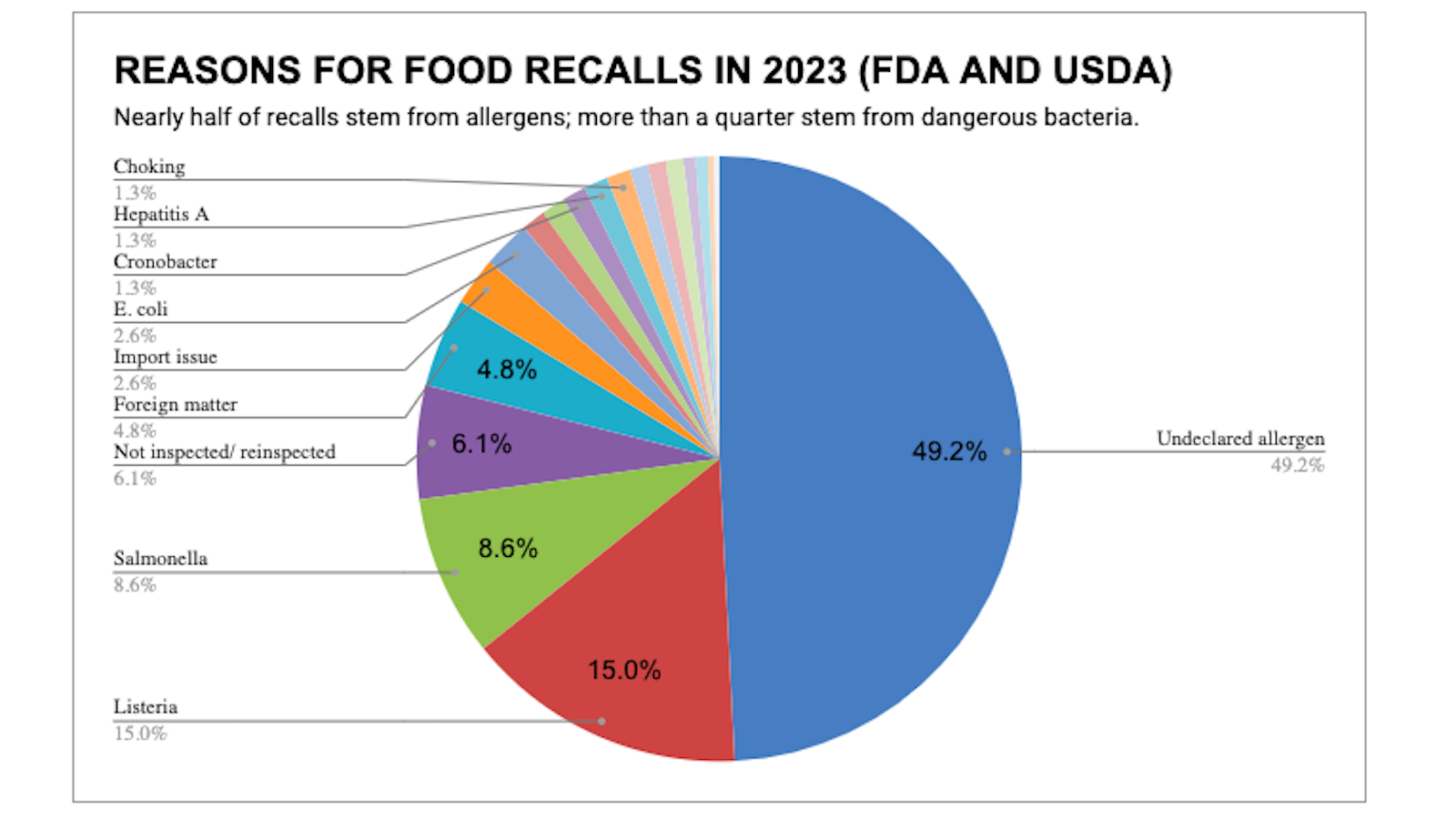

It’s all in the packaging. The number of food recalls and alerts in the United States increased again in 2023, but the total soared primarily because more products failed to disclose allergens.

Overall, 313 recalls and alerts were announced last year by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA.) Recalls and alerts are essentially the same because they both involve food that may be unsafe. Regulators announce recalls for products still for sale; they announce alerts for products that are no longer available for purchase but may be in consumers’ or restaurants’ pantries, freezers or refrigerators. The overwhelming majority of announcements are recalls.

The FDA regulates about 78% of the nation’s food supply, from produce to pet food, from sandwiches to snacks. The FDA’s oversight includes all food except for meat, poultry, and some fish and egg products. Those are regulated by the USDA. Recalls generally occur after companies discover problems, after consumers complain or after regulators conduct testing or inspections.

- The number of recalls breaks down like this: 224 from the FDA and 89 from the USDA

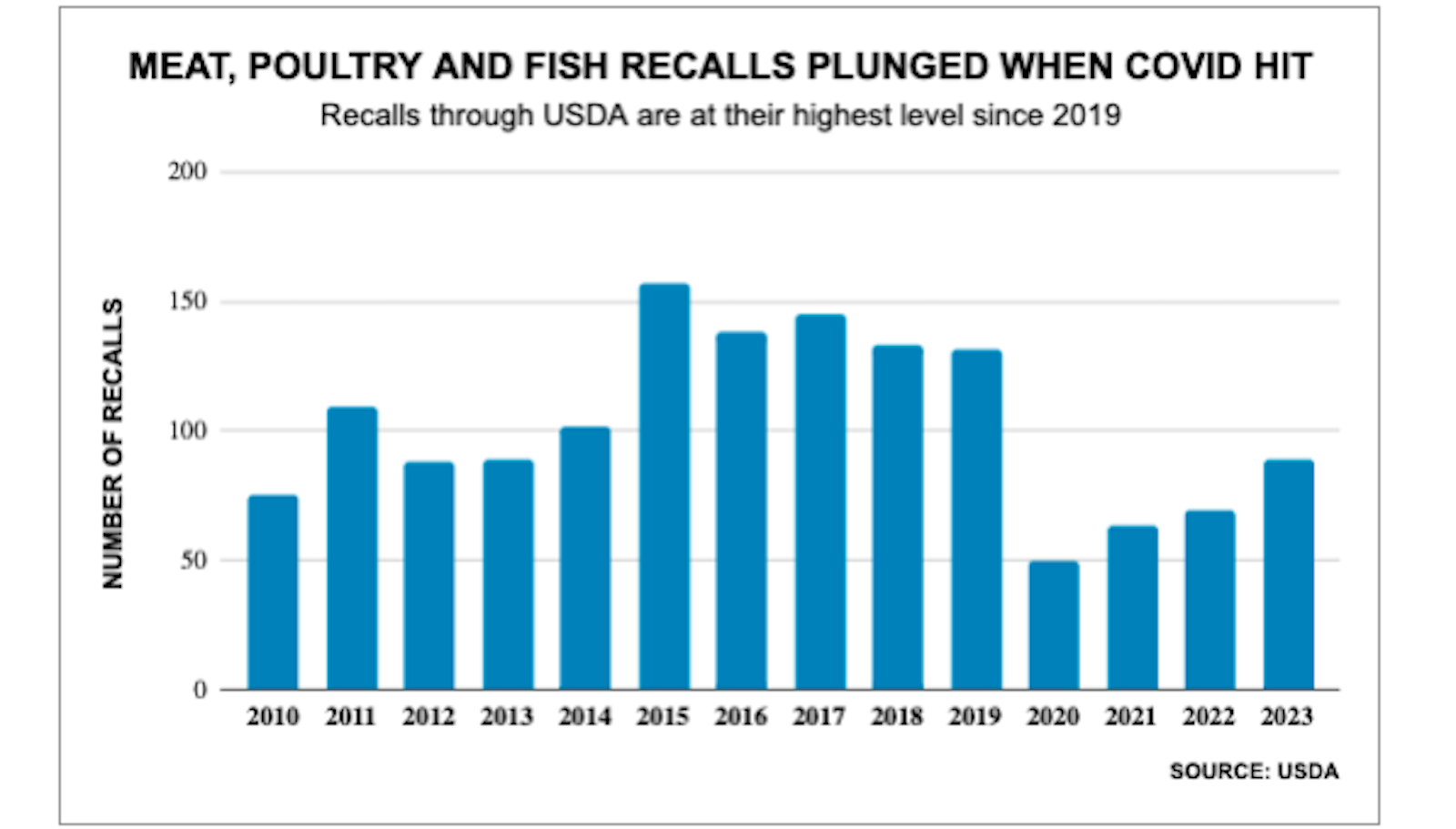

- Total recalls under the FDA have been virtually unchanged for several years. But recalls under the USDA increased significantly in 2023 – by 31% compared with 2022. The total is still far below the totals during the five years before the Last year’s 89 USDA recalls was the highest level since 2019.

- Recalls because food contained metal, plastic or some other potentialThat represents an increase of 8% compared with 2022. But the year- to-year change isn’t as important as the trendline, and we’ll come back to that.

- Most interesting: the number of items recalled because of undeclared allergens soared, increasing by 27% in 2023.

- Nearly all recalls occur because there’s something in there that’s not allowed, such as Salmonella bacteria or metal pieces or rodent droppings or an allergen that wasn’t on the label. Foods aren’t prohibited from containing any of the nine major allergens such as milk or wheat or eggs – if they disclose it on the package.

Other highlights of our analysis:

- Total recalls under the FDA have been virtually unchanged for several years. But recalls under the USDA increased significantly in 2023 – by 31% compared with 2022. The total is still far below the totals during the five years before the Last year’s 89 USDA recalls was the highest level since 2019.

- Recalls because food contained metal, plastic or some other potential hazard dropped by 40% in 2023, from 25 to 15.

- Recalls because of potential Salmonella contamination dropped by 31%, from 39 to 27.

- Recalls because of potential Listeria contamination increased by 9%, from 43 to 47.

- Recalls of pet food increased, from four to Six of those involved Salmonella or other bacteria. Pet food is regulated by the FDA. We care about our pets, but also important: humans can get sick from handling contaminated pet food. In one outbreak, six of the seven sick people were babies 1 year or younger.

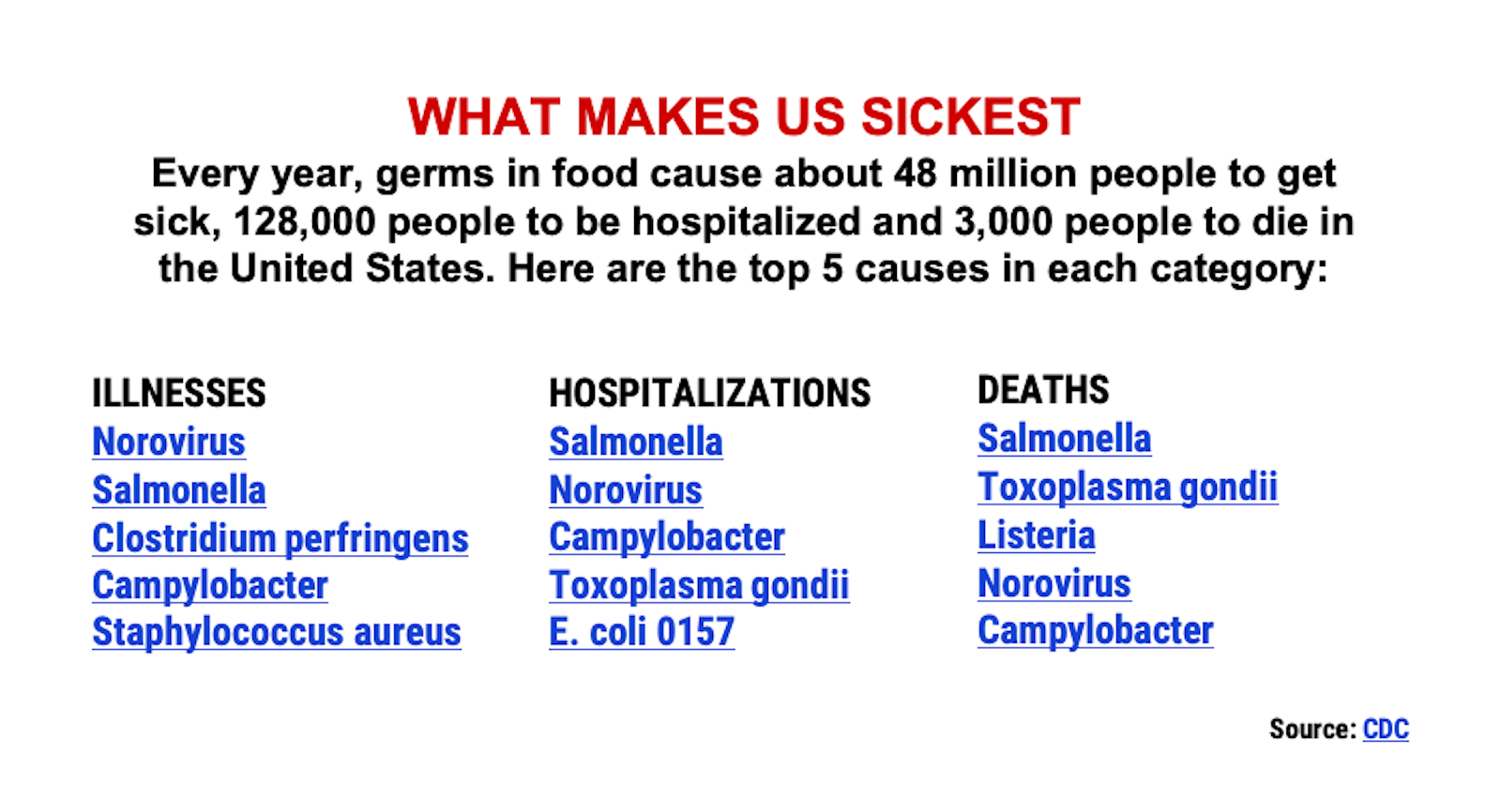

The possibility of buying contaminated food in stores or restaurants isn’t an inconsequential concern. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that nearly 50 million Americans – one in six – become ill every year from contaminated food or beverages. Among those people, 128,000 end up in the hospital and 3,000 die every year.

There’s a decent chance that you or someone close to you has become ill from food poisoning the last few years but didn’t realize it unless you got sick enough to see a doctor. That doesn’t mean you don’t need to be concerned about unsafe food in the future.

You can take steps to minimize your risk by reducing the chance of bacteria multiplying in your food, by handling food safely and by staying up on recalls that might affect you or your family, especially if someone in your home has a food allergy or is elderly, very young, pregnant or immunize-compromised.

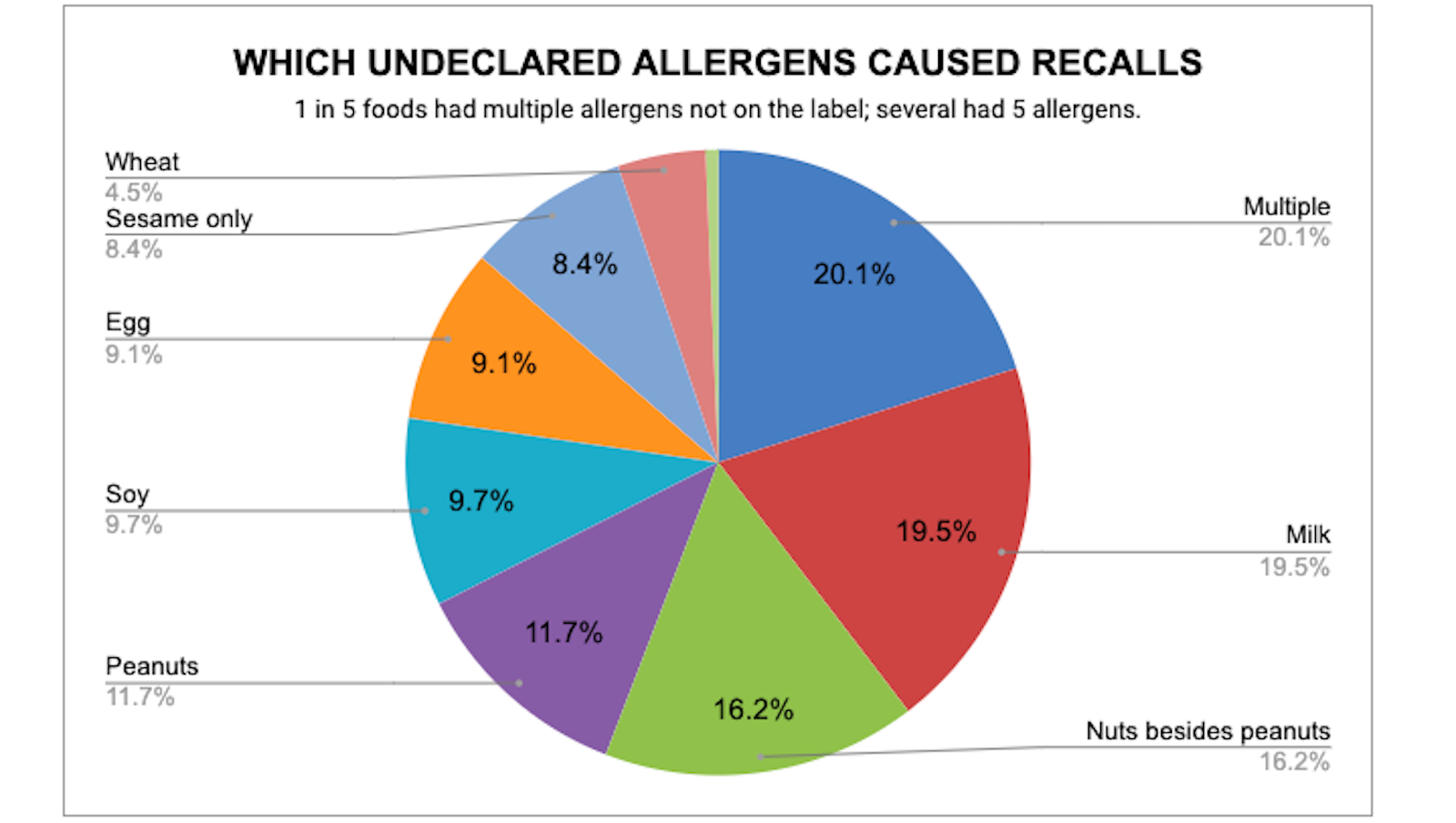

SO MANY ALLERGENS

The biggest development in 2023: A significant increase in foods recalled because of undeclared allergens. Allergies to one or more foods are a growing problem, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, affecting 6% of adults and 8% of children nationwide.

An allergy to food causes an immune system response that can range from mild, such as hives, to severe, such as a fatal inability to breathe.

Nearly half of all recalls in 2023 – 154 foods – were recalled because a known allergen was not disclosed on the label. That’s up from 121 undeclared allergens in 2022.

About 39% of that increase stemmed from undeclared sesame, which is new to the list of allergens that must be disclosed on foods packaged on or after Jan. 1, 2023. Of the 13 recalls only because of sesame in 2023, 11 were under the FDA and two were under the USDA.

With the newest addition, the allergens that require disclosure are:

Crustacean shellfish

Eggs

Fish

Milk

Peanuts

Sesame

Soy

Tree nuts

Wheat

READ MORE ABOUT ALLERGENS

Congress in 2021 passed the Food Allergy Safety, Treatment, Education, and Research Act, known as FASTER. This adds sesame to the list of eight other major allergens that long have required disclosure on food ingredients labels or on a separate “contains xxx” label that is next to the list of ingredients starting last year.

The eight previous allergens account for about 90% of serious reactions.

Allergies are different than food intolerances, which may cause an upset stomach or other condition, but not an immune system response. Examples of intolerances include gluten and lactose.

Other recalls involved sesame too, but those foods also contained other allergens that would have triggered the recall anyway.

One undeclared allergen is bad enough, but in one in five cases of allergen-driven recalls, the foods contained multiple allergens that weren’t disclosed on the label.

FOODBORNE PATHOGENS

After undeclared allergens, the most common reasons for recalls are Listeria, Salmonella, lack of inspection and foreign matter in the food.

Listeria

Listeria led to 47 of the recalls, or 15% of recalls in 2023. There were 43 in 2022, and 56 in 2019. Consuming food contaminated by Listeria monocytogenes bacteria can cause Listeriosis, which can be a serious infection. The CDC estimates that about 1,600 people get Listeriosis every year. About 260 die.

Foods most susceptible to Listeria, per the FDA and CDC:

- Unpasteurized milk, yogurt and soft cheeses.

- Ice cream.

- Raw or processed vegetables.

- Raw or processed fruit.

- Raw or undercooked poultry.

- Unheated cheeses sliced at a deli.

- Unheated deli meat, hot dogs and fermented or dry sausage.

- Premade deli salads, such as coleslaw and potato, tuna, or chicken salad.

- Refrigerated pâté or meat spreads.

- Raw or refrigerated smoked fish.

- Cut melon left out for more than 2 hours (1 hour if outdoors in temperatures hotter than 90°F).

- Cut melon in the refrigerator for more than a week.

Salmonella

Salmonella caused 27 recalls, or 8.6% of recalls in 2023. There were 39 salmonella recalls and alerts in 2022 and 21 in 2019.

Adding all of the bacterial contamination and foodborne pathogens together, they led to 94 recalls, or about 30% of the total.

Salmonella can be quite serious. Each year Salmonella causes an estimated:

- 35 million infections.

- 26,500

- 420 deaths in the United

Consuming or touching food or objects contaminated with Salmonella bacteria can cause infection and illness. That’s why experts urge frequent hand-washing before eating or working in the kitchen or even before putting on makeup or otherwise touching your eyes, nose or mouth.

Illnesses caused by Salmonella occur more often in the summer because the bacteria love warm temperatures and unrefrigerated foods at outdoor gatherings.

Foods most susceptible to Salmonella, per the FDA and CDC:

- Raw or undercooked meat and poultry products.

- Raw or undercooked eggs, egg products and dough.

- Raw or unpasteurized milk and other dairy products.

- Raw fruits and leafy greens.

- Pet food.

- Prepackaged salads.

- Processed foods, such as frozen pot pies and stuffed chicken entrees.

Norovirus

The CDC says Norovirus is No. 1 cause of contaminated food outbreaks in this country, responsible for about 58% of food-related illness outbreaks. It’s estimated that foodborne norovirus costs about $2 billion every year in the United States, primarily because of medical bills and lost productivity.

Each year norovirus causes an estimated:

- 900 deaths, mostly among people age 65 and older

- 109,000 hospitalizations

- 465,000 emergency department visits, mostly by young children

- 2,270,000 outpatient clinic visits annually, mostly by young children

- 19 million to 21 million

Foods most susceptible to norovirus, per the CDC and experts:

- Fresh fruits or vegetables such as leafy greens sprayed with contaminated water while being

- Food handled by restaurant workers or food service workers in schools or health care facilities who are ill.

- Oysters that come from contaminated water or other shellfish that are undercooked.

Most norovirus outbreaks happen in places such as restaurants. One recent example: A norovirus outbreak during the week of Thanksgiving 2022 was blamed on one sick worker at an Illinois restaurant. More than 317 people around Peoria, Ill., who got sick ate at the same restaurant, the CDC report said.

None of the recalls in 2023 were blamed on norovirus. Often, authorities can’t trace it to a particular food because people may not go to the doctor if their symptoms are mild and, even if they did, most hospitals and doctor’s offices do not test for norovirus as a policy, the CDC says.

In addition, even when medical facilities do test for norovirus, then state, local and territorial health departments are not required to report individual cases of norovirus illness to a national surveillance system, although it’s encouraged. Each year, there are about 2,500 reported norovirus outbreaks in the United States. So far, we’re on pace for more cases this year.

There are four norovirus alerts in 2024 as of April 18, all involving oysters:

- FDA Advises Restaurants and Retailers of a Recall of Certain Oysters from Westport, Connecticut

- FDA Advises Restaurants and Retailers Not to Serve or Sell and Consumers Not to Eat Certain Oysters from Baja California, Mexico

- FDA Advises Restaurants and Retailers Not to Serve or Sell and Consumers Not to Eat Certain Frozen, Raw, Half-shell Oysters from Republic of Korea

- FDA Advises Restaurants and Retailers Not to Serve or Sell and Consumers Not to Eat Certain Oysters from Bahia Salina in Sonora, Mexico

In 2022 and into 2023, the CDC investigated two major outbreaks of norovirus linked to raw oysters that were distributed to multiple states. At least 400 illnesses were reported in 19 states. The raw oysters were from Galveston Bay, Texas, and British Columbia.

E. coli

E. coli is another potentially dangerous issue. Eight of the 2023 recalls occurred because of E. coli, down from 10 in 2022. E. coli bacteria are typically in the intestines of people and animals. Most types of E. coli aren’t a threat. But some strains, such as E. coli O157:H7, can cause serious gastrointestinal issues.

Foods most susceptible to E. coli, according to the FDA and CDC:

- Raw and undercooked beef and poultry

- Leafy greens

- Sprouts

- Raw milk

- Raw cheese

TYPES OF FOOD RECALLED MOST OFTEN

Snacks were the most commonly recalled type of food in 2023. Roughly one in five foods flagged were snacks such as cookies, granola bars, candy and popcorn. And virtually all of the snack recalls stemmed

from undeclared allergens, which makes sense: The more ingredients you put into the production process, the more likely it could be that one of the nine big allergens isn’t disclosed on the label.

The other most frequently recalled types of food in 2023:

Cantaloupe All because of Salmonella.

Fruit besides cantaloupe All but one because of Listeria or Hepatitis A.

Beef Usually because of E. coli or foreign matter

Soup Virtually all because of undeclared allergens.

Salad/greens/ kits Usually because of Listeria or undeclared allergens

Poultry Usually because of undeclared allergens or undercooked ready-to-eat items.

Cheese Most because of Listeria.

Vegetables Most because of Listeria.

Supplements Nearly all because of undeclared allergens.

Pet food Nearly all because of Salmonella.

RECALL TRENDS OVER THE YEARS

Food sold in grocery stores or restaurants or other outlets usually gets recalled or flagged in one of four ways:

- People get sick and seek medical care, and then local health officials and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention test fluids and determine the same product caused the exact same illness in at least two people. This is an outbreak.

- Consumers file a complaint with regulators or This often occurs with issues such as spoilage or foreign materials found in food.

- The company self-reports a problem after testing or other discoveries.

- Local, state or federal regulators discover an issue through routine surveillance or specific

While FDA recalls have been at roughly the same level for five of the last six years, 2023 marks the fourth year in a row that recalls through the USDA didn’t reach 100. In fact, recalls through the USDA hadn’t been below 100 since 2013, until 2020.

Read more about trends

We know recalls and alerts for meat, poultry and fish through the USDA fell dramatically when COVID hit. The USDA announced 131 recalls in 2019; that dropped to 50 in 2020 – a decline of 62%. The number has been climbing every year since. It’s notable that the USDA announced 20 recalls and alerts in the first three months of 2024, putting it on pace to tally 80 this year, which would not be a significant change.

It’s unclear whether this is the new normal, whether meat and poultry are safer today or whether the industry is still recovering from the massive disruptions during the pandemic, such as ongoing shortages of government and corporate food inspectors and some people’s reluctance to go to a doctor or urgent care unless absolutely necessary.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Adulterated cantaloupe, onions and peaches killed people last year and a wide variety of foods including ice cream and lettuce made more than 1,100 people sick. Those are just the ones we know about. We know the actual total of illnesses is much higher because many people recover from food poisoning without medical attention.

When we have thousands of people getting sick every year from a particular contaminated food item, we should think hard about what else can be done. We need to stop contaminated food from being sold, identify it more quickly when something does slip through and warn consumers when contaminated food makes it to store shelves.

The last one – warning consumers – should be the easiest part. The CDC says many illnesses occur long after recalls have been announced – sometimes weeks or months later – because people just didn’t know about the danger. There’s no single method of reaching everyone who may have purchased a particular product. Multiple methods of outreach would be better.

Here are some steps that would help:

- The FDA and USDA should develop a way for consumers and businesses to receive direct email, text or phone alerts of all Class I recalls and any allergens of concern. Products with undeclared allergens such as milk, peanuts or wheat comprised nearly half of all recalls in 2023. Allergies to one or more foods affect 6% of adults and 8% of children nationwide.

2. The FDA and USDA together post an average of a half-dozen recalls a week. Many aren’t a huge risk to most Yes, you can sign up for email alerts – for every food recall. If someone were to get email or text alerts about every single recall – one almost every day on average – they’d suffer from what experts call “recall fatigue.” Many consumers would become numb and stop noticing or would get annoyed by all of the alerts and stop reading them.

The FDA and USDA should revamp their alert process so people could opt to be notified about specific categories of recalls and alerts, instead of all of them. Maybe someone wants to be alerted only to foods recalled because of undeclared nuts or wheat or soy. Maybe someone wants to be notified only about issues with pet food.

An even better idea: It’d be great if the two regulators created an app that works like the Food Recalls app by SmartAddress Inc. Users can choose to get real-time alerts for microbes including Salmonella and Listeria, or just for pet food, or for all food and beverage recalls through both the FDA and USDA. If you don’t want real-time notifications on your phone, you can just check the app once a day or once a week or whenever you’d like.

3. A separate idea that we probably will see at some point in the future: Food producers could leverage technology so consumers can easily learn whether an item they have has been Currently, consumers can use an app such as FoodSwitch or Yuka to scan the barcodes for many food items and find out what’s in it and the nutritional value.

What if every food product contained a QR code, for example, so you could scan it with your phone and find out about any recalls in real time. This would also help address the issue of recalled foods at food pantries and soup kitchens. They don’t have the computer systems a grocery store has, so volunteers have to go through products by hand to find recalled items.

4. Companies need to do more. Currently, government regulators require only two notifications when there’s a food recall: a posting on the FDA’s recall website, and a news release issued by the company that’s conducting the recall.

5. Companies conducting a recall should be required to try to reach out to consumers. Many food manufacturers sure spend a lot of money to market their products to us. How about if they spend the same amount that was spent to sell us the product to inform us that it’s been recalled?

6. In addition, retailers should offer shoppers a way to be contacted by phone, text or email in case of recalls involving items they bought, whether that’s through a loyalty card or some other system. Retailers are inconsistent here. In a survey we conducted in 2022, we found that only half of the 50 largest U.S. grocery and convenience chains we talked with offered a way for customers to be contacted directly about recalls. Some retailers post recall notices in their stores. It might be in the section where the item was sold or it could be at the customer service counter. For big recalls, some post a notice at the front entrance.

But those don’t help people who aren’t regular shoppers, or don’t visit that section of the store the next time they shop, or order their groceries online and pick them up curbside or get them delivered.

Grocers should ask themselves whether posting in-store notices of Class I recalls would reach some people who otherwise wouldn’t find out. A multi-layered approach to communication can help: traditional media, social media, websites, loyalty cards, automated phone calls, emails and/or in- store notifications.

7. The FDA needs to implement the part of the Food Safety Modernization Act that requires retailers to post recall notices in a consistent manner.

8. Consumers should do more to be informed, particularly if their home includes people with severe food allergies, or young children, senior citizens, pregnant women or others who are medically more vulnerable to foodborne illness. Consumers should be proactive to make sure they have multiple ways to find out about recalls through their grocers, free apps, government alerts and news alerts.

HOW TO FILE A COMPLAINT ABOUT POSSIBLE FOOD CONTAMINATION

- Meat, poultry, fish and egg products are regulated by the USDA. File a complaint online here. Or call the USDA’s Meat and Poultry Hotline at 1-888-MPHotline (1-888-674-6854.)

- All other food and beverage items, including pet food are regulated by the FDA. File a complaint online here.Or call the FDA’s main emergency number at 1-866-300-4374.

- For issues with restaurant food, call the health department in your city, county or state. You can find contact information for your state here.

Topics

Authors

Teresa Murray

Consumer Watchdog, U.S. PIRG Education Fund

Teresa directs the Consumer Watchdog office, which looks out for consumers’ health, safety and financial security. Previously, she worked as a journalist covering consumer issues and personal finance for two decades for Ohio’s largest daily newspaper. She received dozens of state and national journalism awards, including Best Columnist in Ohio, a National Headliner Award for coverage of the 2008-09 financial crisis, and a journalism public service award for exposing improper billing practices by Verizon that affected 15 million customers nationwide. Teresa and her husband live in Greater Cleveland and have two sons. She enjoys biking, house projects and music, and serves on her church missions team and stewardship board.

Find Out More

Safe At Home in 2024?

5 steps you can take to protect your privacy now

Too much to recall