Highway Boondoggles 6

Big Projects. Bigger Price Tags. Limited Benefits.

In our sixth annual Highway Boondoggles report we profile six budget-busting highway expansion projects that are poised to go forward amid COVID-related budget shortfalls.

Downloads

NJPIRG Law & Policy Center

Executive summary

America’s aging roads and bridges are in increasingly dire need of repair. Tens of thousands of people die on the roads each year and more are sickened or die from air pollution caused by vehicles. Tens of millions of Americans lack access to quality public transit or safe places to walk or bike, leaving them fully dependent on cars or – for those who cannot afford a car or are physically unable to drive – entirely shut off from critical services and opportunities.

America was already faced with the need to make critical transportation investments. And then COVID-19 hit, upending travel patterns and undercutting the traditional sources of government transportation revenue.

Now is no time to fritter away scarce public resources on wasteful boondoggle projects.

Yet across the country, state and local governments continue to move forward with tens of billions of dollars’ worth of new and expanded highways that do little to address real transportation challenges, while diverting scarce funding from much-needed infrastructure repairs and key, future-oriented transportation priorities. Highway Boondoggles 6 finds seven new budget-eating highway projects slated to cost a total of $26 billion that will harm communities and the environment, while likely failing to achieve meaningful transportation goals.

Highway expansions are expensive and saddle states with debt.

-

In 2014, the latest year for which data is available, federal, state and local governments spent $26 billion on highway expansion projects – sucking money away from road repair, transit and other local needs.

-

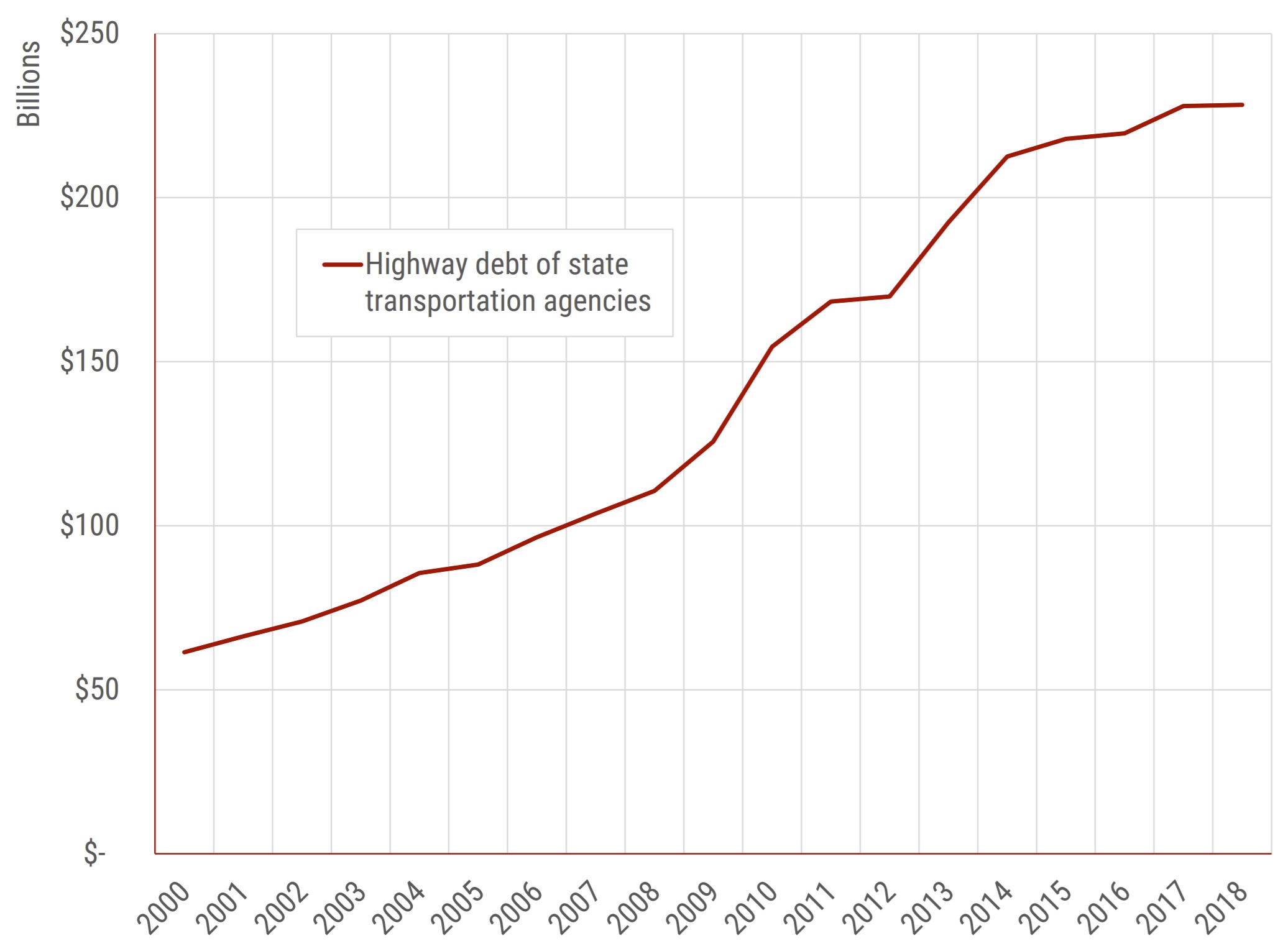

From 2008 to 2018, the highway debt of state transportation agencies more than doubled from $111 billion to $228 billion.

-

New roadways are expensive to maintain and represent a lasting financial burden on the American people. The average new lane-mile costs $24,000 per year to keep in a state of good repair.

Highway expansion doesn’t solve congestion.

-

Expanding a highway sets off a chain reaction of societal decisions that ultimately lead to the highway becoming congested again – often in only a short time. Since 1980, the nation has added more than 870,000 lane-miles of highway – paving more than 1,652 square miles, an area larger than the state of Rhode Island – and yet pre-COVID congestion was worse than it was in the early 1980s.

Highway expansion damages the environment and our communities.

-

Highway expansion fuels additional driving that contributes to climate change. Transportation is the nation’s number one source of global warming pollution.

-

Pollution from transportation causes tens of thousands of deaths in the U.S. each year and makes Americans more vulnerable to diseases like COVID-19.

-

Highway expansion can also cause irreparable harm to communities – forcing the relocation of homes and businesses, widening “dead zones” alongside highways, severing street connections for pedestrians and cars, and reducing the city’s base of taxable property.

Figure ES-1. The highway debt of state transportation agencies has doubled since 2008 (nominal)

States continue to spend billions of dollars on new or expanded highways that fail to address real problems with our transportation system and will create new problems for our communities and the environment. Questionable projects poised to absorb billions of scarce transportation dollars include:

-

Cincinnati Eastern Bypass; Ohio; $7.3 billion: Ohio’s plan to build a 75-mile bypass around the eastern side of Cincinnati would cause sprawling development and overwhelm the Ohio Department of Transportation’s construction budget.

-

Loop 1604 Expansion; Texas; $1.36 billion: A major expansion to a 23-mile section of Loop 1604 in San Antonio would threaten the Edwards Aquifer, which supplies drinking water to millions of people in the region.

-

I-57 Interchange; Illinois; $205.5 million: Dubbed the “Exit to Nowhere,” the proposed interchange would connect drivers to a non-existent and heavily criticized proposed third airport outside of Chicago.

-

Birmingham Northern Beltline; Alabama; $5.3 billion: The Alabama Department of Transportation is pushing a project reliant on intermittent and insufficient federal funding, which could take 40 years to complete.

-

I-526/Mark Clark Extension; South Carolina; $725 million: The project, which will cost Charleston County more than it has spent on any single project in its history, would save commuters just seconds of travel time.

-

M-CORES; Florida; $10+ billion: Florida’s 330-mile, three-highway construction project, which is already straining the state budget, would destroy critical open spaces and threaten the survival of the endangered Florida panther.

-

Southeast Connector; Texas; $1.6 billion: The expansion of three highways in the Fort Worth area by up to six lanes in each direction would induce sprawl and damage local communities, but is still moving forward even as the city’s transit system struggles to provide basic service.

In addition, the Allston Multimodal Project in Boston is a $1 billion project that, in its current form, is inconsistent with the city and state’s commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and encourage a shift away from driving. There is no escaping the need for major investment in transportation infrastructure in this section of Boston – yet without changes, the project could make it more costly and difficult for Massachusetts meet the transportation challenges of the 21st century.

Federal, state and local governments should stop or downsize unnecessary or low-priority highway projects. Specifically, policymakers should:

-

Invest in transportation solutions that reduce the need for costly and disruptive highway expansion projects. Investments in public transportation, changes in land-use policy, road pricing measures, and technological measures that help drivers avoid peak-time traffic, for example, can often address congestion more cheaply and effectively than highway expansion.

-

Adopt fix-it-first policies that reorient transportation funding away from newer and wider highways and toward repair of existing roads, bridges and transit systems.

-

Use the latest transportation data and require full cost-benefit comparisons, including future maintenance needs, to evaluate all proposed new and expanded highways. This includes projects proposed as public-private partnerships.

-

Give priority funding to transportation projects that reduce growth in vehicle-miles traveled, to account for the public health, environmental and climate benefits resulting from reduced driving.

-

Invest in research and data collection to better track and react to ongoing shifts in how people travel.

Topics

Find Out More

Less driving is possible

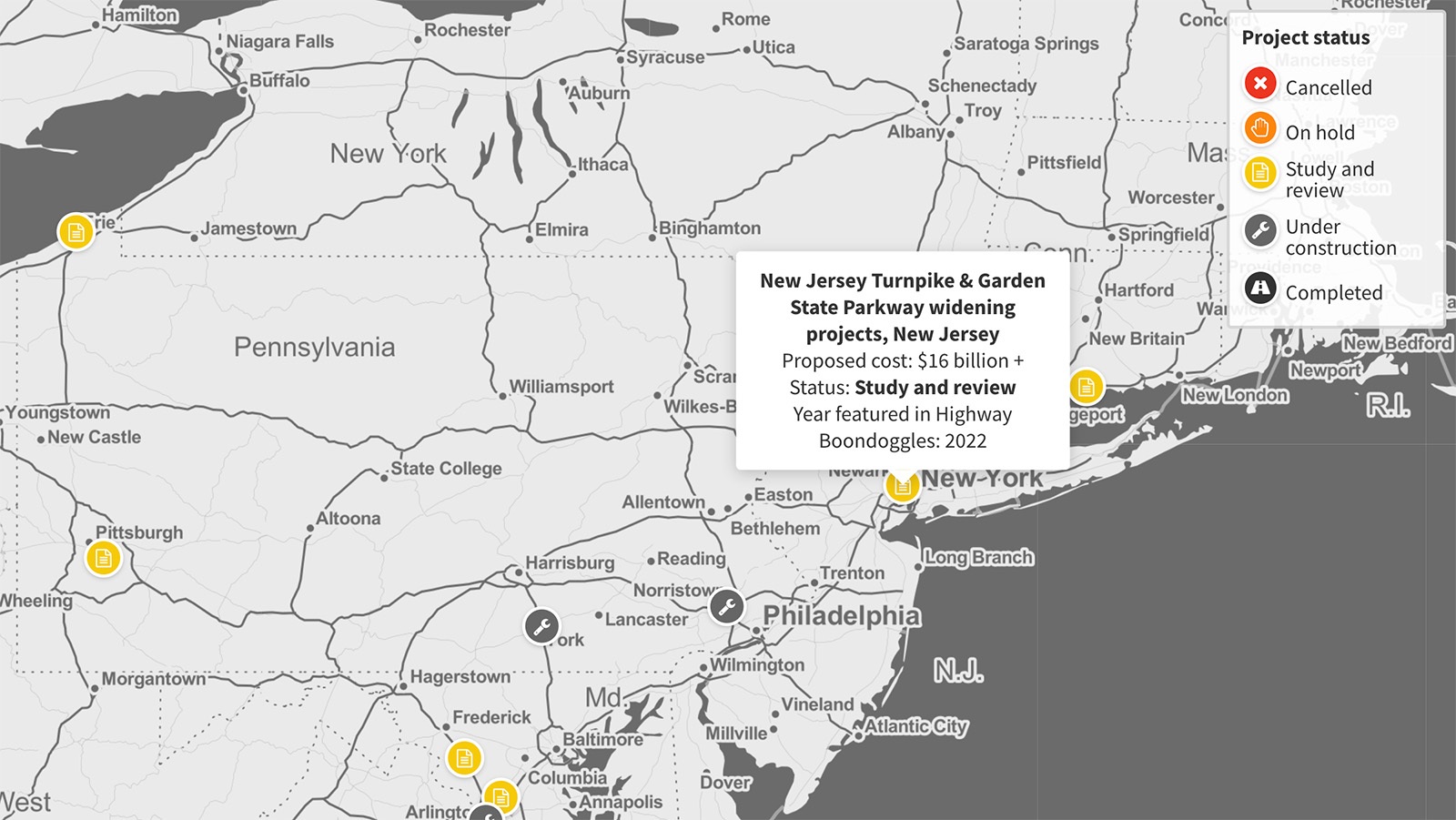

New Jersey Turnpike & Garden State Parkway widening projects