Following the Money 2014

How the 50 States Rate in Providing Online Access to Government Spending Data

This report, NJPIRG LPC’s fifth annual evaluation of state transparency websites, finds that states are making progress toward comprehensive, one-stop, one-click transparency and accountability for state government spending. Over the past year, new states have opened the books on public spending and several states have adopted new practices to further expand citizens’ access to critical spending information. Many states, however, still have a long way to go to provide taxpayers with the information they need to ensure that government is spending their money effectively.

Downloads

Executive Summary

Every year, state governments spend tens of billions of dollars through contracts for goods and services, subsidies to encourage economic development, and other expenditures. Accountability and public scrutiny are necessary to ensure that the public can trust that state funds are well spent.

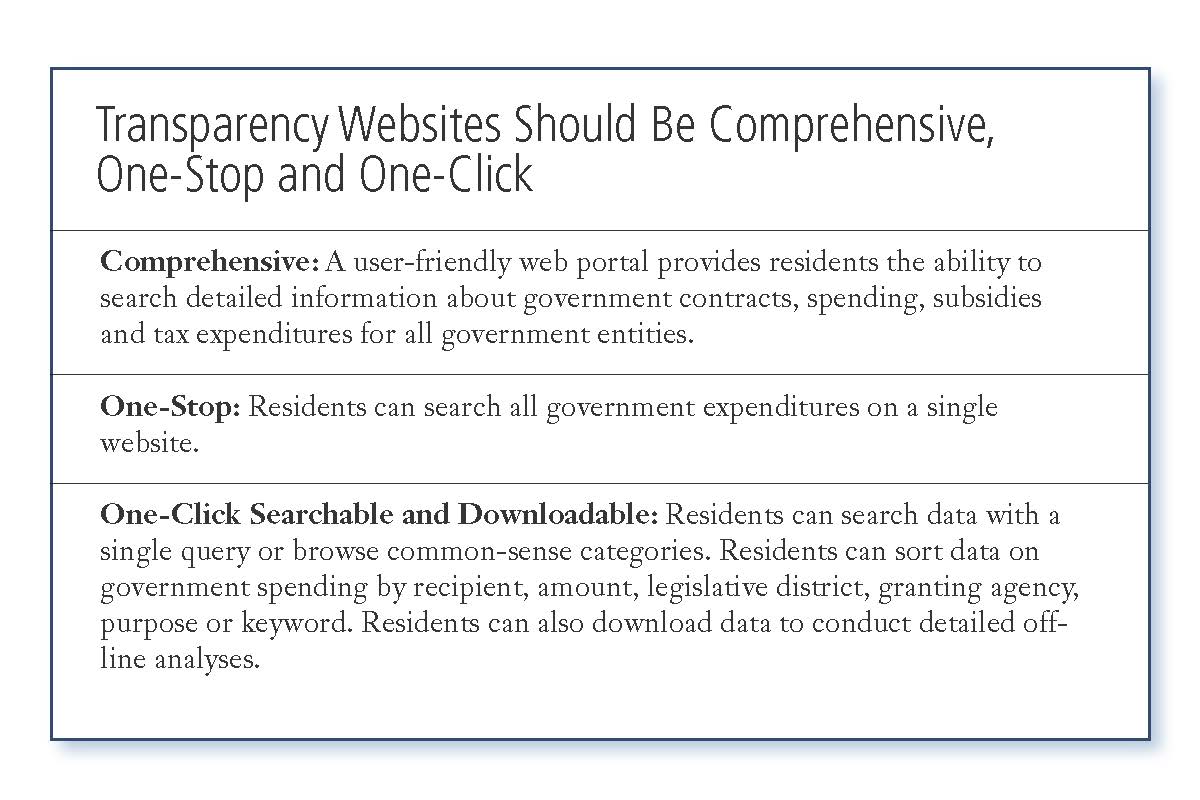

In recent years, state governments across the country have created transparency websites that provide checkbook-level information on government spending – meaning that users can view the payments made to individual companies as well as details about the purchased goods, services or other public benefits. These websites allow residents and watchdog groups to ensure that taxpayers get their money’s worth.

Last year was the first time that all 50 states operated websites to make information on state spending accessible to the public. These web portals continue to improve. For instance, in 2014, 38 states’ transparency websites also provide checkbook-level detail on subsidies for economic development. Many states are also disclosing information that was previously “off budget” and are making it easy for outside researchers to download and analyze large data sets about government spending.

This report, U.S. PIRG Education Fund’s fifth annual evaluation of state transparency websites, finds that states are making progress toward comprehensive, one-stop, one-click transparency and accountability for state government spending. Over the past year, new states have opened the books on public spending and several states have adopted new practices to further expand citizens’ access to critical spending information. Many states, however, still have a long way to go to provide taxpayers with the information they need to ensure that government is spending their money effectively.

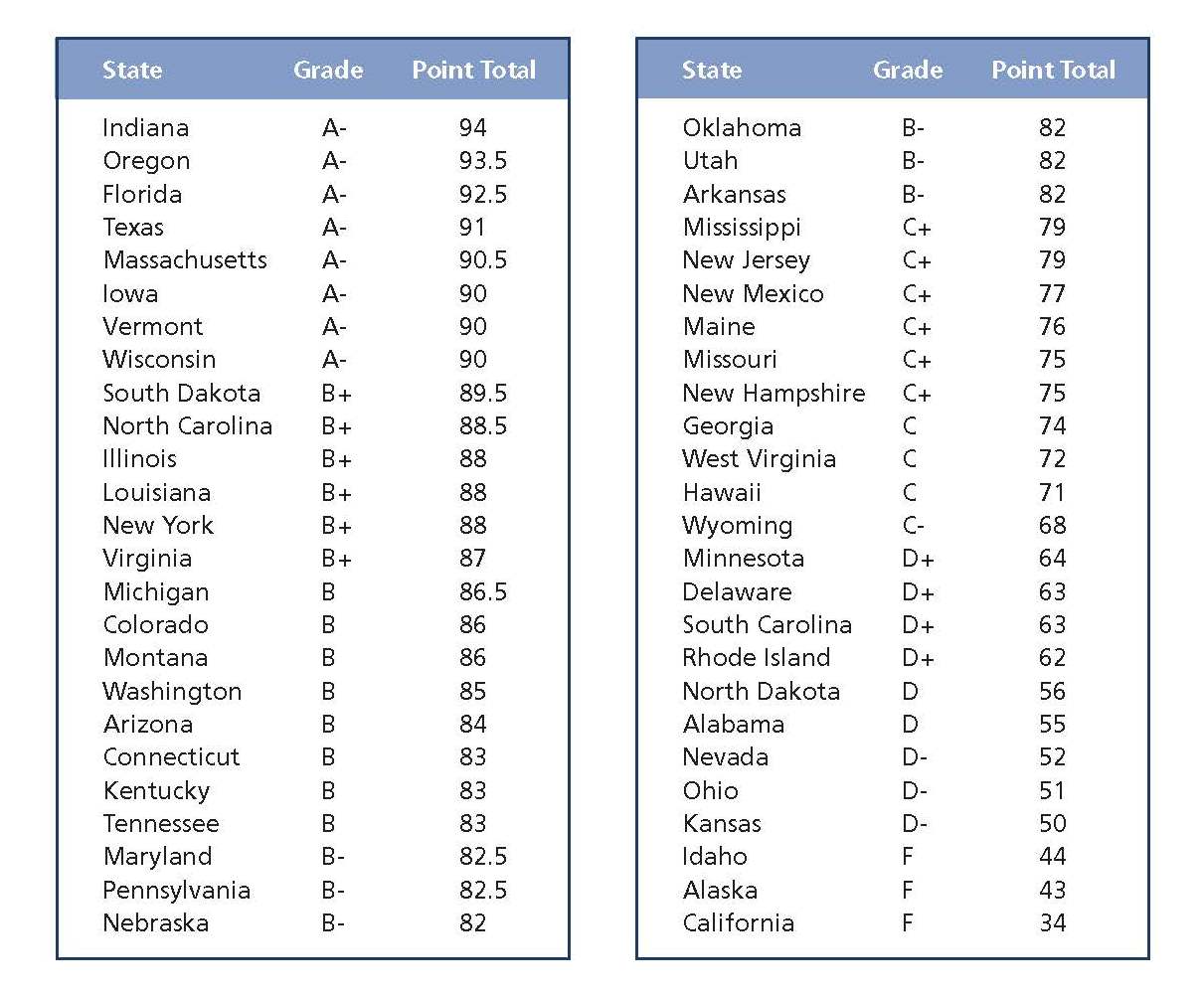

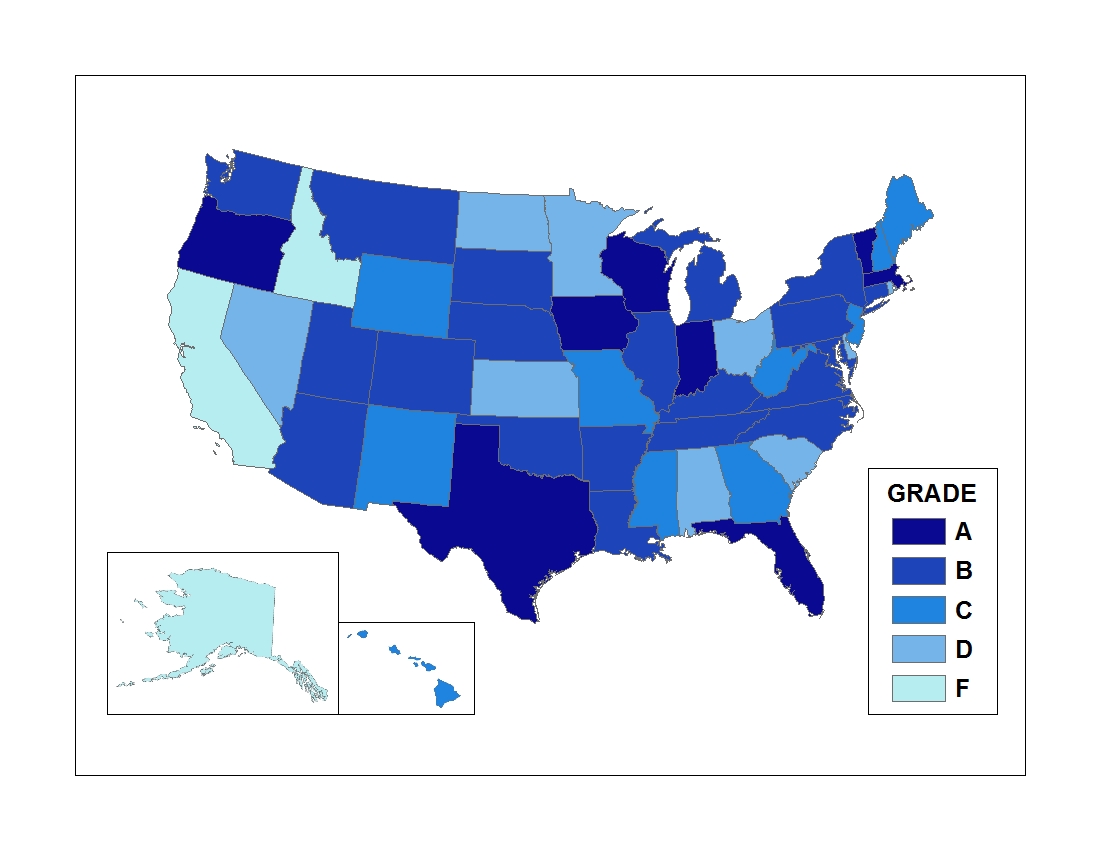

Figure ES-1: How the 50 States Rate in Providing Online Access to Government Spending Data

Over the past year, several states have launched new websites or made substantive upgrades to their existing websites. For example:

• Wisconsin launched OpenBook Wisconsin, which enables users to browse the payments made to vendors based on the vendor’s name, the purchasing agency or the type of expenditure. The checkbook is updated every two weeks and contains expenditure information dating back to fiscal year 2008.

• Vermont unveiled a new checkbook tool that enables users to view the state’s payments to vendors from 66 departments, agencies and other government entities dating back to fiscal year 2011.

States have made varying levels of progress toward improved online spending transparency. (See Figure ES-1 and Table ES-1.)

• Leading States (“A” range): The eight states leading in online spending transparency have created user-friendly websites that provide visitors with accessible information on an array of expenditures. Not only can ordinary citizens find information on specific vendor payments through easy-to-use search features, but experts and watchdog groups can also download and analyze the entire checkbook dataset.

• Advancing States (“B” range): Twenty states are advancing in online spending transparency, with spending information that is easy to access but more limited than Leading States. Most Advancing States have checkbooks that are searchable by recipient, keyword and agency.

• Middling States (“C” range): Ten states are middling in online spending transparency, with comprehensive and easy-to-access checkbook-level spending information but limited information on subsidies or other “off-budget” expenditures.

• Lagging States (“D” range): Checkbook-level spending in the nine Lagging States is less accessible to users than checkbook-level spending in other states. For example, while these states provide the public with the ability to search for specific payments, residents cannot download and analyze the entire dataset.

• Failing States (“F” range): Three states are failing to meet several of the standards of online spending transparency. For instance, while these states provide checkbook-level information, the spending data are not available in searchable online tools.

Some states are innovating new features for online transparency. They have developed new protocols and datasets, giving the public unprecedented ability to monitor and influence how their government allocates resources. For instance:

• Massachusetts has awarded more than $300,000 in grants to six cities to post their spending information online. In total, Massachusetts plans to help 20 cities post their spending information online by January 2015.

• South Dakota audits its checkbook every year, which enables users to have greater confidence in the veracity of the data and to report publicly on facts and trends they find in state spending.

• Tennessee posts the value of payments excluded from the checkbook for confidentiality reasons – such as for foster care and adoption assistance – enabling users to better understand even those state payments that policies prevent from being listed in the checkbook database.

All states, including Leading States, have many opportunities to improve their transparency.

• Not a single state provides checkbook-level spending information on all of its quasi-public agencies – which demand particular openness because they typically remain outside the normal checks and balances of the budget process.

• Fifteen states do not provide any recipient-specific details on the benefits – either projected or actual – of economic development subsidies. Only six states provide checkbook-level information on the subsidy recipients for each of the state’s most important economic development programs.

• The checkbooks in three states – Alaska, California and Ohio – cannot effectively be searched at all.

• Seventeen states do not allow users to download the entire checkbook dataset for offline analysis.

• Six states do not provide tax expenditure reports that detail the impact on the state budget of specific targeted tax credits, exemptions or deductions.

Table ES-1: How the 50 States Rate in Providing Online Access to Government Spending Data