Tell the FTC: Stop tech companies from selling kids’ data

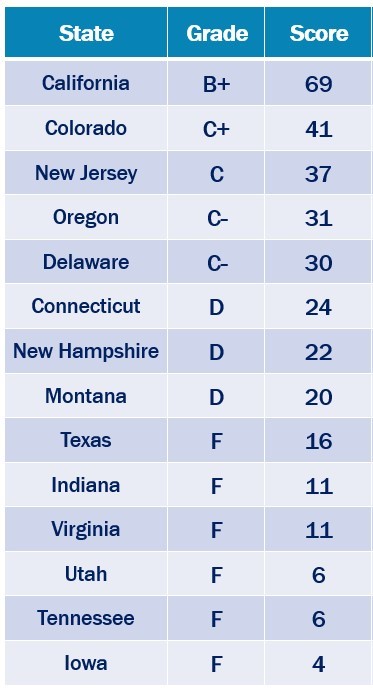

Of the 14 states that have passed data privacy laws, nearly half of them receive a failing grade.

Sign the petition

Across the country states are passing consumer privacy laws. It might sound like a good thing. After all, the U.S. currently lacks a federal comprehensive privacy law, and the more specific laws that do exist haven’t kept up with the times. HIPAA, for example, doesn’t protect the data that health websites, apps, or wearables like FitBits collect about us. Something needs to change.

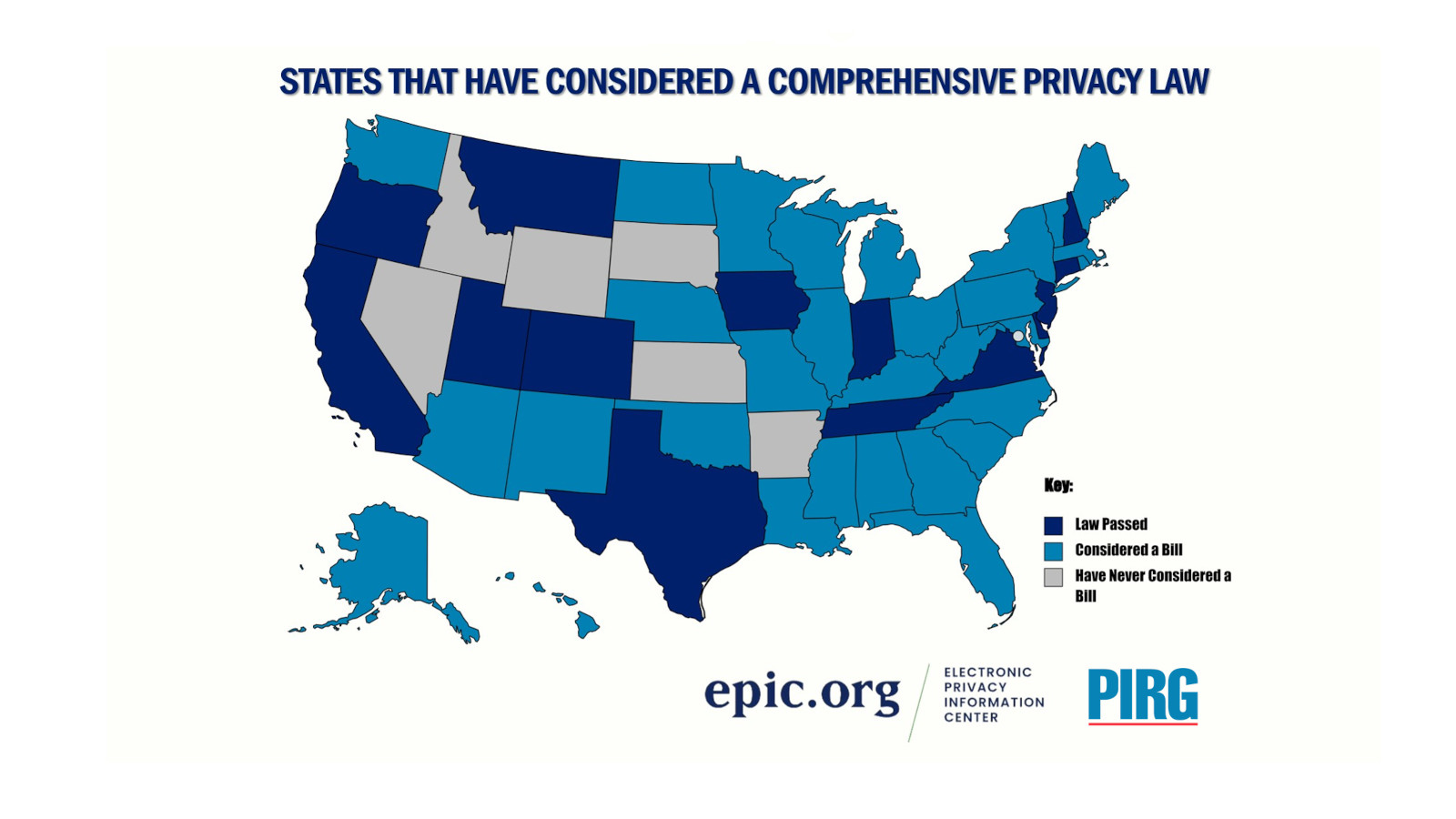

Since 2018, 44 states have considered comprehensive consumer privacy bills that purportedly aim to protect people’s privacy and security. So far 14 states have passed them. Many of these bills, however, have been heavily influenced by companies such as Amazon, leading to significantly weakened consumer protections across the country.

We partnered with our friends over at EPIC to grade state privacy laws. The bad news: Of the 14 state privacy bills that have passed, nearly half fail to protect people’s personal information. The good news: It’s not too late to change course.

Photo by Edmund Coby, PIRG staff | TPIN

Right now we’re all having our data collected way more often than we realize, and it’s getting sold to a bunch of companies we’ve never even heard of. That puts our personal security at risk.

Almost every company we interact with collects some amount of data on us. Sometimes it’s data that makes sense. Amazon needs your shipping address, and Uber needs your location. When data collection gets out of hand, however, it can cause you big problems. And today, it’s getting out of hand a lot.

The fast-food chain Tim Hortons was accused by Canadian authorities of using its mobile app to harvest users’ location data 24/7, even when the app was closed. According to a Mozilla Foundation investigation last year, all 25 major car brands may collect data including health diagnoses and genetic information from your car’s computers and apps.

Companies not only gather unnecessary data, they often use your data for irrelevant purposes. A study by Human Rights Watch, for example, found that educational apps and websites used by schools were harvesting the data of millions of schoolchildren and sending it to third parties while students learned. We found Mastercard monetizes your credit card transaction history by making it available to the online advertising industry.

The websites and apps you rely on often have secret tracking technology like cookies in the background. Tracking cookies stay on your browser or device long after you’ve left a webpage or even shut down your computer for the day. They follow you across sites over time, collecting information like your location and browsing and search history. They then transmit that information to third party companies you’ve never heard of, and those companies turn around and sell your data to even more companies you’ve never heard of. These companies are called data brokers, and they are particularly bad for your security.

The more data companies collect, the more dangerous it is for you. And the more entities companies share your data with, the more likely it is that your personal information will be exposed in a breach or a hack. Your bank account number could end up with identity thieves. Your contacts could end up with scammers. Your phone number can end up on annoying robocall and robotext lists.

Data security problems affect millions every year. In 2022, the FTC received more complaints about identity theft — over 1.1 million complaints from consumers — than any other category. The second most common complaint was about imposter scams — schemes where fraudsters falsely claim to be a relative in distress or a business a consumer has shopped at previously requesting money or personal information. In 2022, consumers lost nearly $2.7 billion to imposter scams. The more personal information scammers have about a consumer’s life, the more convincing these scams become.

Data brokers and the online advertising industry that harvest a lot of our information are particularly dangerous. Every time we load a webpage that shows us a targeted ad, there’s a big auction happening in the background with companies exchanging our browsing, location and other data. A recent study found that these auctions expose the average American’s data 747 times per day.

All across the country, tech and other companies are pushing for weak laws. Of the 14 laws states have passed so far, all but California’s closely follow a model that was initially drafted by industry giants such as Amazon. From tech to telecomms, there’s a lot of companies making a lot of money in data.

In 2021, Virginia became the second state in the nation to pass a comprehensive consumer data privacy law. Where California’s law — which was passed in 2018 — established some real protections, Virginia’s was almost entirely void of meaningful provisions. A notable difference: While California’s rules became law in response to a proposed ballot question, Virginia’s legislation had been handed to the bill sponsor by an Amazon lobbyist, and it was based on an earlier bill from Washington state that had been modified at the behest of Amazon, Comcast, Microsoft, and other industry lobbyists.

The Virginia law was weak. Companies could continue collecting whatever data they want as long as it was disclosed somewhere in a privacy policy. While consumers could, in theory, request companies delete their data, they would have to submit requests one at a time to the hundreds — if not thousands — of entities holding their information. Consumers also had no ability to hold companies accountable in court for violating the privacy law meant to protect them. (Virginia gets an F in this scorecard.)

Virginia is what the lobbyists were asking for...But making it as weak as Virginia is something I have never understood.Rep. Collin Walke, on his privacy bill

Former Oklahoma State Representative

Unfortunately, Virginia became the model state legislators have been pushed to match. In Oklahoma, former state legislator Collin Walke was asked to water down his 2021 Oklahoma Computer Data Privacy Act.

“It was a bipartisan bill,” Walke said in an interview for this report. “People liked it. Before it even hit the House floor it had some 40 co-authors. It passed out of the House 85-11.” When Walke’s bill stalled in the Senate, he knew he was going to have to negotiate some changes. What he didn’t expect, however, was the lobbyist push for a noticeably weaker, Virginia-style bill.

“Virginia is what the lobbyists were asking for,” Walke said. “Making the bill weaker, I understood. Compromise is always necessary. But making it as weak as Virginia is something I have never understood.”

Photo by Edmund Coby, PIRG staff | TPIN

More recently, some lobbyists have pivoted to pushing the “Connecticut model” — pretty similar bill to Virginia, but with a couple of actual perks for consumers. Most notably, Connecticut allows consumers to use a browser tool to automatically opt-out of websites collecting data. That is pretty neat. The law, however, included no ability for someone like the Attorney General to specify what that tool should look like. (And it really needed that. Deep inside the privacy policy of almost every website you use is some line about not listening to ‘Do Not Track’ signals. You want someone to be really clear about what does and doesn’t count in these circumstances.)

The story in Connecticut is the story of other states. What passed in 2022 ended up notably weaker than what co-sponsor Sen. Bob Duff had introduced every year previously since 2019. As he told the Markup, during a hearing on his bill in 2020 the room was “literally filled with every single lobbyist I’ve ever known in Hartford, hired by companies to defeat the bill.” Connecticut gets a D in this scorecard.

In 2023, we saw a lot of lobbyists pushing state legislators to weaken their bills to match VA and/or CT. In Oregon, for example, the State Privacy and Security Coalition — an industry group representing Amazon and Meta, among others — testified at one point that a stronger draft of the Oregon Consumer Privacy Act “still deviate[d] from other state privacy laws” as to “need significant work.” In Delaware, the Computer Communications Industry Association — an industry group representing Google and Apple, among others — encouraged in testimony that the state’s bill should “more consistently align with definitions and principles in other existing comprehensive state privacy laws,” pointing to Virginia and Connecticut specifically.

Industry lobbying has been fast and heavy. An investigation by the Markup identified that in the 31 states that heard privacy bills in 2021 and 2022, there were 445 active lobbyists and firms representing Amazon, Meta, Microsoft, Google, Apple and industry front groups. Because of how bad state lobbying disclosures are (believe us, we’ve tried too), that number is likely an undercount.

These industry-preferred bills aren’t just a bad deal for the residents of those states. Where the states go, Congress often follows. The more states that coalesce around regulations heavily shaped by the industry they’re meant to regulate, the lower the bar we’re setting for a federal law in the future. And given how we haven’t been able to update any of our previous federal small-potatoes privacy bills like HIPAA for the world of smartphones, a bad law today could mean a bad law for all of us for 20+ years.

The consumer data laws we’re seeing now just don’t do enough to change the status quo. They generally allow consumers to access, correct, and delete personal data companies have about them – but sending requests, one at a time, to every company that’s ever held their information. These laws only work if you vast swaths of time to do so, which, seriously, no one does.

There are ways to protect consumers’ data security. Instead of bad bills, states should:

In our scorecard, if a state did all of that, it’d get an A+.

California first passed the CCPA in 2018, and then made it stronger in 2020. Last year, it passed the DELETE Act, giving people the ability to tell hundreds of data brokers to delete their data with one push of a button.

Things California does well:

Things it could do better:

Colorado passed the Colorado Privacy Act in 2021. In July 2024, Colorado residents will be able to download a special browser tool to automatically broadcast to websites they don’t want their data to be collected. (Read our guide on that here).

Things Colorado does well:

Things it could do better:

New Jersey’s Senate Bill 332 (name still pending) is one of the most recent states to pass a privacy law. The governor signed it into law on Jan. 16, 2024.

Things New Jersey does well:

Things it could do better:

Passed in June 2023, the Oregon Consumer Privacy Act was the result of a working group led by the Oregon Attorney General’s office. Despite this, it still followed the Connecticut model, though Oregon did add some important protections – including minimizing the number of entities who were exempt from the law.

Things Oregon does well:

Things it could do better:

The Delaware governor signed the Personal Data Privacy Act into law on Sept. 11, 2023. The legislature was pressured by industry groups to water it down to match Connecticut and Virginia.

Things Delaware does well:

Things it could do better:

Connecticut’s Data Privacy Act was first introduced in 2019 and originally included strong provisions such as a private right of action. The bill, however, was whittled down over time, making it more similar to Virginia’s failing law. In 2022, Connecticut’s bill was passed with a few additional provisions — such as requirements to honor global opt-out signals — making it a little stronger than Virginia. This bill has now become a favored piece of template legislation for lobbyists, particularly in bluer states.

A year after its original passage, Connecticut passed legislation amending the law to include heightened protections for kids and teens online and adding a category of sensitive data for “consumer health data.” The “Connecticut model” pushed by industry in other states does not include these updates.

Things Connecticut does well:

Things it could do better:

New Hampshire is the most recent comprehensive consumer privacy law to pass. The bill passed out of the Legislature on Jan. 18, 2024 and is awaiting the governor’s signature.

Things New Hampshire does well:

Things it could do better:

Before Republican Sen. Daniel Zolnikov introduced the Consumer Data Privacy Act, a tech lobbyist told him the Connecticut model was too difficult for industry to comply with and that it would be better to introduce something closer to the weaker Virginia model. According to Politico, after Zolnikov heard the same lobbyist testify in Maryland — a blue state — that industry would be happy with a Connecticut model, he strengthened his bill.

Zolnikov has expressed frustration with being pushed to pass a weaker bill in Montana than in blue state counterparts. “I’m not an idiot,” Zolnikov said in an interview with Politico after the passage of his bill, directing his comments at the lobbyist. “And you treating us in Montana like a bunch of rural backwoods folks is quite an insult.”

Things Montana does well:

Things it could do better:

Texas passed the Texas Data Privacy and Security Act in June, 2023. Unfortunately, there’s a lot it could do better when it comes to protecting consumers.

What Texas does well:

What it could do better:

While the TDPSA leaves a lot to be desired, last year Texas enacted a pretty great data broker registry law. This will require data brokers – shadowy companies that specialize in harvesting and selling data – to register with the state. That’s a win for transparency. The next step? Maybe Texas will pass its own DELETE Act, and let consumers tell all those data brokers to delete their data with the click of one button.

In 2021, Virginia became the 2nd state to pass a data privacy law. The original bill text was handed to the sponsor by an Amazon lobbyist, enshrining such industry-friendly measures it’s hard to say this bill does all that much for consumers. It’s gone on to be a favorite template of industry lobbyists across the country, pushing states to all match Virginia’s bad standard.

Indiana passed the Indiana Consumer Data Protection Act in May, 2023. Unfortunately, like with all of the other states that get a failing grade, it provides no meaningful privacy protections to consumers.

Tennessee passed the Tennessee Information Protection Act in May, 2023. Unfortunately, like with all of the other states that get a failing grade, it provides no meaningful privacy protections to consumers.

Utah passed the Utah Consumer Privacy Act in March, 2022. It started with a Virginia model, and then weakened it by making the law apply only to businesses making more than $25 million a year.

Unfortunately, like with all of the other states that get a failing grade, it provides no meaningful privacy protections to consumers.

Iowa passed the Iowa Data Privacy Act in March, 2023. Unfortunately, like with all of the other states that get a failing grade, it provides no meaningful privacy protections to consumers.

While the state of consumer data protection is not strong currently, the good news is nothing is permanent. Legislators in Illinois, Massachusetts and Maine, for example, are considering strong bills with data minimization and giving consumers the ability to hold companies accountable in court.

Even states that have passed imperfect laws can still improve. Amendments are always possible. A year after enacting the Connecticut Data Privacy Act, the state passed amendments to better protect health data and heighten protections for kids and teens online.

We think a part of the problem is that a lot of people don’t know this is happening. A lot of industry’s pull happens in backrooms or in hearings that don’t get much attention. We hope to help give state legislators a different place to look for support crafting state bills. And we hope to educate everyone about how to increase their personal security.

All states still have the ability to better protect their residents’ personal security.

Right now, there are no rules stopping tech companies from monetizing the data of kids and teens.

Sign the petition

R.J. focuses on data privacy issues and the commercialization of personal data in the digital age. Her work ranges from consumer harms like scams and data breaches, to manipulative targeted advertising, to keeping kids safe online. In her work at Frontier Group, she has authored research reports on government transparency, predatory auto lending and consumer debt. Her work has appeared in WIRED magazine, CBS Mornings and USA Today, among other outlets. When she’s not protecting the public interest, she is an avid reader, fiction writer and birder.