The FTC is cracking down on big healthcare companies

Corporations are becoming the norm in health care, and agencies like the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) know that what's good for business isn't necessarily good for patients.

Corporations are becoming the norm in healthcare, and agencies like the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) know that what’s good for business isn’t necessarily good for patients. When healthcare companies merge, monopolies can form, allowing a handful of hospital networks to charge high prices unchallenged.

The FTC has been taking a more active role in cracking down on anti-competitive business deals. In 2022, the Commission brought 24 merger enforcement challenges against various companies—the second highest number recorded in the last decade. Their enforcement prevented unlawful mergers in numerous sectors of the economy, including consumer goods and services, high tech and industrial goods, and energy. In the healthcare industry in particular, preventing consolidation is crucial to protect patients.

Consolidation leads to fewer options and higher prices.

Of the 60 leading pharmaceutical companies in 1995, mergers over the following 20 years reduced that number to just 10. This worrying trend of pharmaceutical company consolidation has made it harder for people to afford the medicines they need. Similar trends can be seen in other segments of the healthcare industry, with large hospitals absorbing local doctor’s offices and clinics, and with insurance companies that merge with provider groups. These changes reduce competition and raise prices.

Rural communities are often hit the hardest when large healthcare corporations begin to buy up their hospitals. Fewer hospitals make it harder for patients to get care. For example, studies show that many small rural hospitals are forced to eliminate crucial service lines such as obstetrics and maternal care after mergers. These cuts come because the larger hospital corporation deems them less profitable or less important. In rural communities, the elimination of just one or two competitors gives the remaining hospitals monopoly or near-monopoly power to set prices without fear of competition. Insurers have to include those higher-priced hospitals in their network because they have no other option for the patients enrolled in their plans. Patients and their insurers have few or no other options.

The lack of competition exists even in big cities, as we’ve seen in Pittsburgh where there are essentially only two large hospital systems left for its residents. Healthcare sectors are merging, and consolidation is a key reason why patients and employers are paying higher prices for insurance, hospital care and prescription medications. But we have the power of the FTC to help protect us from mergers that are bad for patients.

What is the FTC doing to protect patients?

To make sure mergers don’t harm consumers or stifle competition, the FTC has the power to review some potential mergers. The FTC analysts vet proposed mergers that are valued above $200 million. If they find the deal would substantially prevent competition, the FTC can initiate litigation against corporations to block the merger from happening.

FTC takes action against healthcare providers.

In 2021, FTC took active steps to regulate the healthcare industry. Take the case of DaVita, a company that operates dialysis clinics. Notably, there are only three providers of dialysis services in the state of Utah. Almost 90% of dialysis clinics there are either owned by DaVita or the University of Utah. DaVita’s intention to purchase 18 additional clinics in the state raised concerns about their already high and growing market share. Additionally, DaVita was using anti-competitive hiring practices–colluding with rival companies not to poach each other’s senior-level employees, restricting job movement. This was a bad move for patients in Utah, especially considering DaVita’s recent negative press from wrongful death lawsuits.

The FTC successfully ordered DaVita to halt its new acquisitions and force DaVita to sell three of its Utah clinics to a rival firm. They also ordered them to seek approval for all new acquisitions, and stop the employee restrictions. This mandate stops them from engaging in further anti-competitive behavior and prevents a near-monopoly.

FTC takes action against a pharmaceutical merger.

In September 2023, the FTC took legal action against pharmaceutical giant Amgen, which planned to buy rival company Horizon for $27.8 billion. Horizon’s small portfolio rests on two main drugs: Tepezza and Krystexxa, which treat thyroid eye disease and gout, respectively. The FTC argued that Amgen would likely “bundle” these two drugs with Amgen’s much larger lineup of products. The bundle would allow Amgen to offer a discount to insurance companies if their products were chosen over competing options for patients. This would entrench Krystexxa and Tepezza’s dominance in the market and drive out hopeful competitors for these two drugs—allowing Amgen to raise prices unchallenged later on.

The FTC ultimately settled with Amgen, eliciting a promise not to bundle their products. Some critics claim the settlement will likely be ineffective. They argue that drug companies have a long history of finding loopholes to maximize profits, and it is difficult to prove wrongdoing when drug negotiations are often confidential.

Limits on the FTC’s power and capacity make it difficult to prevent all anticompetitive mergers.

The FTC’s need for improved tools and enforcement power to protect patients was a big factor in the outcome of the Amgen case. Firstly, taking corporations to court can be a costly and time-consuming process, and FTC budget cuts aren’t helping. Second, this case wasn’t a clear cut case of a horizontal or vertical merger. Historically, antitrust cases against horizontal mergers are the most likely to win. When two rival companies selling competing products plan to merge, it is easier to prove the anticompetitive effects of a planned merger. Occasionally, a vertical merger, mergers of two companies making different products in the same industry (like an insurance company and a provider group), will be denied as well. But the Amgen-Horizon merger didn’t fall into either category, and the lack of established guidelines around these merger types made the case more difficult to argue in court.

New FTC guidance will make it easier to review mergers for anticompetitive effects.

Fortunately, the FTC released new merger guidelines in December 2023. The new guidelines lower the threshold to prove a merger is presumptively anticompetitive and provide specific criteria for reviewing the different kinds of mergers. They now encompass more unconventional anticompetitive practices as well: mergers that are neither horizontal or vertical, serial acquisitions, and deals affecting employees as well as consumers. These guidelines show the FTC’s commitment to prosecuting antitrust cases, and demonstrate a more robust stance against anti-competitive practices.

There still remains much to be done. The cases that make the news only represent the most prominent mergers, a tiny fraction of the whole. Many smaller mergers go unnoticed and unreviewed, leading to the gradual disappearance of independent health clinics and practices—and options for patients—as they are consolidated by large healthcare companies. Importantly, the effects of mergers are extremely difficult to reverse once they’ve been completed. Preemptive review of potential mergers by the FTC or states’ Attorneys General is essential. Hopefully, these new FTC guidelines will provide the first step in creating an improved healthcare industry that puts patients first.

Topics

Authors

Maribeth Guarino

High Value Health Care, Advocate, U.S. PIRG Education Fund

Maribeth educates lawmakers and the public about problems in health care and pushes for workable solutions. When she's not researching or lobbying, Maribeth likes to read, play games, and paint.

Catherine Tan

Winter 2024 Intern

Catherine is a sophomore at Colby College interning with PIRG on our Healthcare campaigns.

Find Out More

Medical bill fees and strange add-on charges

Why hasn’t the government protected our rights in the medicine we helped to fund?

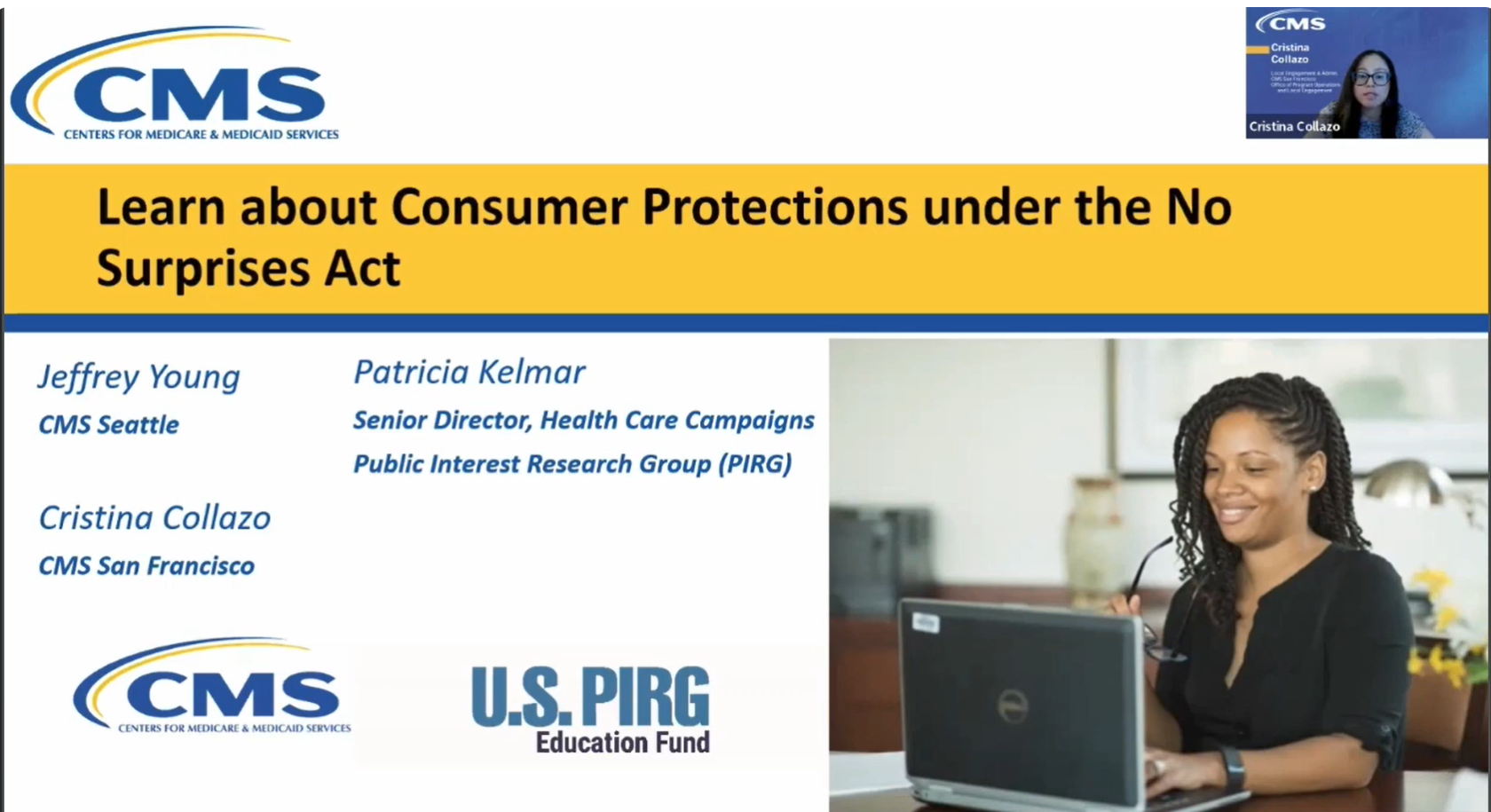

Learn about medical bill protections under the No Surprises Act