Colorado’s Waterways and Microplastics

A Survey of Rivers and Streams along Front Range Watersheds in Colorado

Our survey of sixteen water bodies found microplastics in all sixteen. Microplastics threatens wildlife, ecosystems and our health.

Downloads

The authors would like to thank Gabriel Curcio and Michael Casler for their important contributions to making this report a reality.

Executive Summary

Plastic is everywhere and in everything. It’s used as packaging, it’s in food service products, and it’s in clothing. All told, Americans generate over 36 million tons of plastic waste every year, but less than 6% is recycled. Often when talking about plastic pollution, the images that come to mind are sea turtles and birds ensnared in bags or straws, massive trash gyres in the Pacific Ocean, or whales washed ashore with hundreds of pounds of plastic waste in their stomachs. So it may not be surprising that in one study, as of 2012, 59% of 135 seabird species had ingested plastic, with that number expected to rise to 99% by the year 2050.

Plastic use and pollution is pervasive, even here in scenic “Colorful Colorado.” In 2020, we estimated that every day, Coloradans went through 4.6 million bags and 1.2 million polystyrene cups. Plastics are often a common form of litter recovered in Colorado waterway cleanups, and the Colorado Department of Transportation spends millions of taxpayer dollars each year cleaning litter from roadsides.

But litter alone doesn’t capture the full scope of plastic pollution. Research suggests that we could be missing 99% of the plastic that makes its way into the environment. That’s because plastic doesn’t degrade in the environment like an apple or a piece of paper; instead it breaks into smaller and smaller pieces of plastic called microplastic, which is plastic less than 5mm in length, or smaller than a sesame seed.

A growing area of concern regarding our plastic waste is the environmental and public health threat posed by these microplastics. They are severe laceration and starvation hazards to wildlife and have been found in our air, food, and bodies. Microplastics also attract pollutants that may already exist in the environment at trace levels, accumulating toxins like DDT & PCBs and delivering them to the wildlife that eat them, often bioaccumulating through the food chain.

Microplastics can enter our environment through a myriad of pathways. Litter, illegal dumping, and plastic waste are all obvious culprits. Microfibers are another prevalent type of microplastics and are introduced into the environment through clothes washing as well as usual wear and tear. With wastewater treatment plants unable to fully filter these plastic fibers out, they can end up washed into waterways and ultimately in drinking water. The creation of new plastic products uses small pellets called nurdles which are easily lost and frequently enter waterways. Packaging and the factory processes in the creation of products like bottled water can even cause microplastic contamination.

A prime location for testing microplastics is therefore in our waterways. Colorado’s rivers begin in state and then flow outside making it a headwater state. The river systems originating high in the Rocky Mountains drain into one-third of the landmass of the lower 48 United States. According to Ceres, just one of the seven major river basins of the state, the Colorado Basin, supplies water to nearly 40 million people and sustains a $5 billion agriculture industry. On the eastern side of the state, the South Platte River Basin supplies industrial and municipal water for about 5 million people, 3.5 million acres of farmland, and supports numerous recreational and wildlife areas.

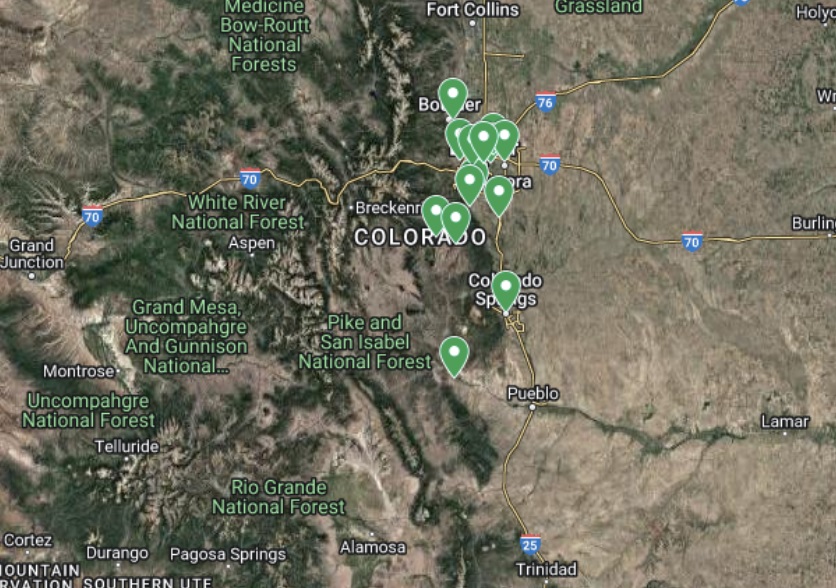

To better understand the scope of the microplastic problem in Colorado, Environment Colorado Research and Policy Center volunteers sampled 16 different water bodies in the Front Range. We found microplastics in 100% of our samples.

Green pins indicate sites where samples were takenPhoto by Staff | TPIN

For an interactive map with pictures of the sites, click here.

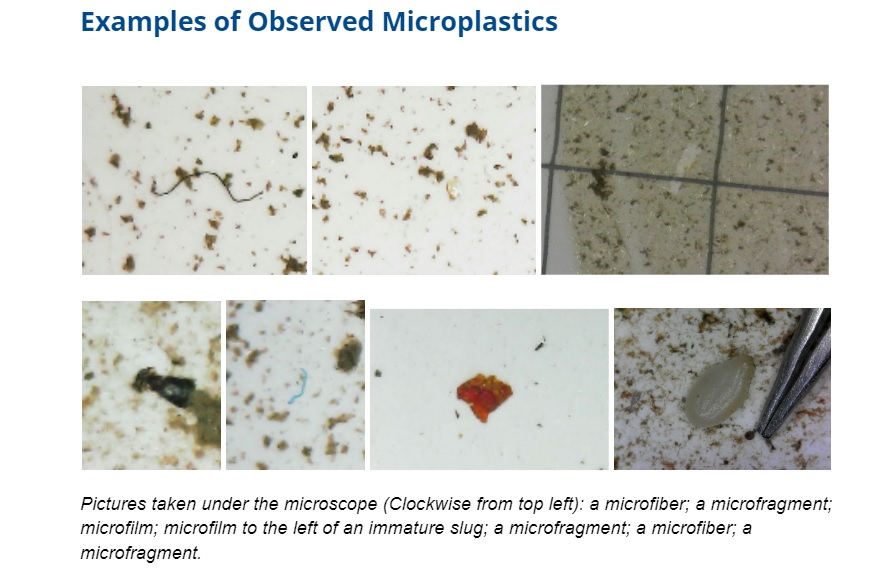

Our project took samples from waterways between February and April of 2023 and tested them for four types of microplastic pollution:

- Fibers: primarily from clothing and textiles;

- Film: primarily from bags and flexible plastic packaging;

- Fragments: primarily from harder plastics or plastic feedstock;

- Beads: primarily from facial scrubs and other cosmetic products.

The results we found were troubling:

- 100% of the sites we sampled had microfibers;

- 88% of the sites we sampled had microfilm;

- 75% of the sites we sampled had microfragments;

It’s clear that the scope of plastic pollution along parts of the Front Range is extensive . In order to address the environmental and waste crisis being caused by our overreliance on plastics, our leaders at the federal, state, and local levels should implement policies that have been previously passed and consider new action.

We offer the following recommendations:

- Phase out single-use plastics – In 2024, Colorado laws will go into effect that phase out polystyrene cups and containers and single-use plastic bags. In 2024, preemption will also be lifted, allowing local communities to go further to target other single-use plastic items like straws and utensils.

- Implement Colorado’s Producer Responsibility law – Producer responsibility is a mechanism to shift the costs and management of postconsumer waste from local governments and consumers and onto producers themselves. Done well, these programs can disincentivize unnecessary plastic packaging production and use. In 2024, the General Assembly will need to approve a producer responsibility draft plan to keep implementation moving forward.

- Halt policies that promote increased manufacture & use of single-use plastic – Communities and legislators across Colorado should oppose subsidies and tax breaks for new petrochemical infrastructure that doubles down on the fossil fuel-to-plastics pipeline. For example, the City of Greeley is considering a “Waste to Energy,” pyrolysis plant that would depend on a stream of plastics to function.

- Tackle fast fashion – Clothing production and use is responsible for up to 22 million metric tons of microplastics that could end up in our oceans between 2015 and 2050.21 Retailers must stop sending overstock, unsold and unused clothing, to landfills and incinerators and should also move away from making products containing synthetic plastic fibers, which inevitably become microplastic pollution. The state should consider legislation if companies do not take action.

- Support reuse – Using items that are designed for reuse can reduce the quantity of plastic we produce and contaminate our waterways. Cities and the state could support reuse including grants to help restaurants invest in cleaning equipment or update public health laws to allow customers to use their own reusable containers to take food to go.

Topics

Authors

Danny Katz

Executive Director, CoPIRG Foundation

Danny has been the director of CoPIRG for over a decade. Danny co-authored a groundbreaking report on the state’s transit, walking and biking needs and is a co-author of the annual “State of Recycling” report. He also helped write a 2016 Denver initiative to create a public matching campaign finance program and led the early effort to eliminate predatory payday loans in Colorado. Danny serves on the Colorado Department of Transportation's (CDOT) Efficiency and Accountability Committee, CDOT's Transit and Rail Advisory Committee, RTD's Reimagine Advisory Committee, the Denver Moves Everyone Think Tank, and the I-70 Collaborative Effort. Danny lobbies federal, state and local elected officials on transportation electrification, multimodal transportation, zero waste, consumer protection and public health issues. He appears frequently in local media outlets and is active in a number of coalitions. He resides in Denver with his family, where he enjoys biking and skiing, the neighborhood food scene and raising chickens.

Lexi Kilbane

Microplastics Project Coordinator, Environment Colorado Research and Policy Center

Alexis Kilbane is a two-year Denver resident and graduate student at the University of Denver. In addition to a Master of Arts in International Human Rights, she is pursuing a certificate in Global Environmental Change and Adaptation. In the spring of 2023, she coordinated the development of our microplastics report.

Find Out More

Refill, Return, Reimagine: Innovative Solutions to Reduce Wasteful Packaging

Truth in recycling

Plastic bag bans work