New proposed income-based fixed charges in California would devalue energy conservation

California electricity rates are some of the highest in the nation.

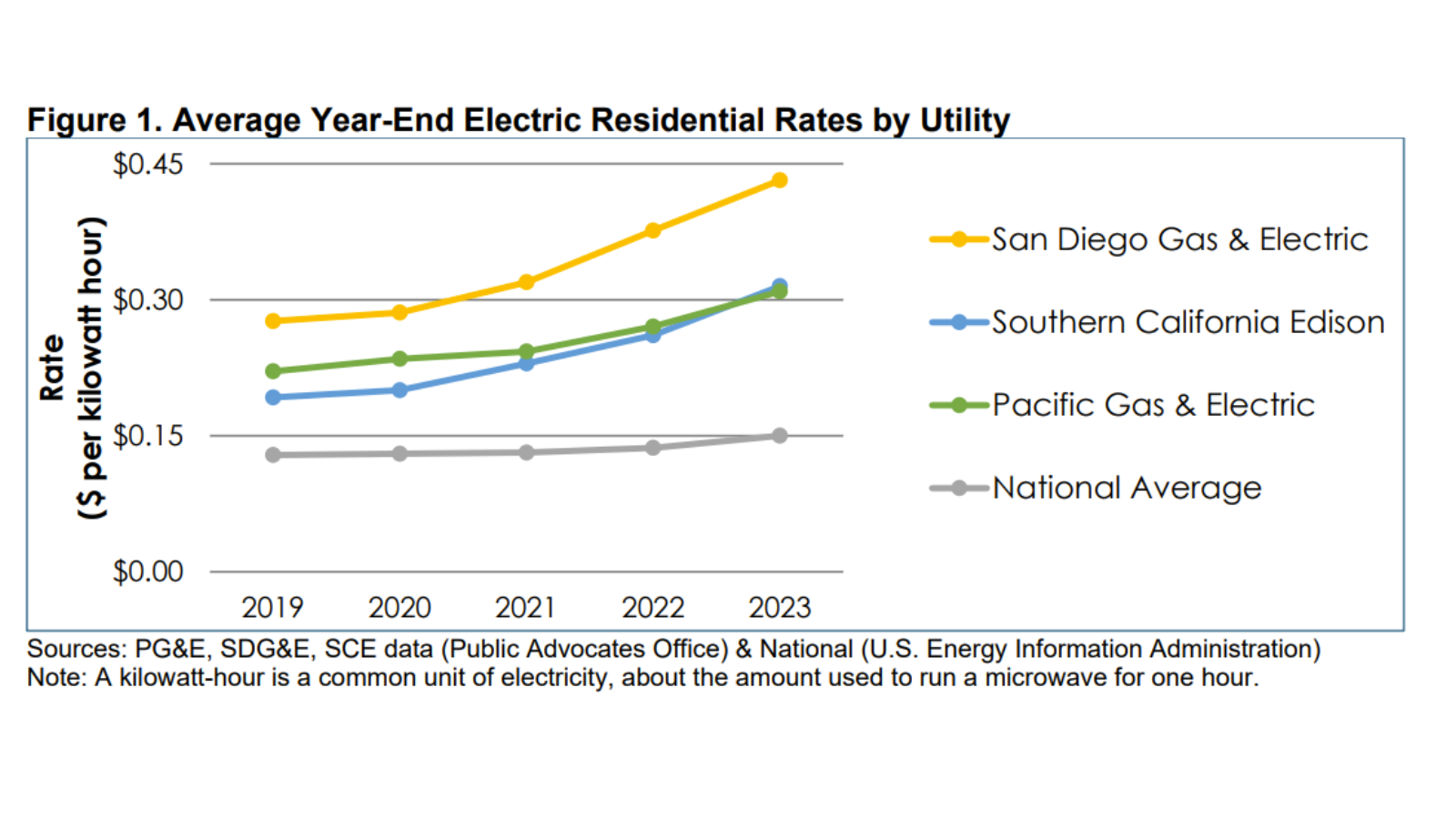

California electricity customers pay rates two to three times higher than the national average. The rates are not only high compared to other utilities, but also compared to what the rates were just two decades ago. Since 2014, electric rates in California have increased 77% to 105% (depending on the provider). The graph below from the California Public Advocates Office shows California utility rates compared to the national average.

To be clear, the part of the electricity rates that are way too high in California are the delivery rates. There are two parts of any utility bill — delivery rates, which are what you pay to the utility to deliver the electricity to your home or business (including the costs of the poles and wires, operations, etc) and supply rates, which are what you pay for the electricity itself (the cost for gas plant or the wind farm or solar installation to generate the electricity). The problem we have in California is that delivery rates are high.

Why are delivery rates so high? There are multiple reasons. California is a big state with high operating costs for building and maintaining long distance power lines, and our extreme weather means costly wildfire liability. That’s unfortunate but understandable. But on top of that, California allows utilities a higher-than- average profit rate and very high expenses for top management. For example, San Diego Gas and Electric allowed one of the highest profit return rates among utilities in 2022 at 10.2%. Those costs are wrapped into the excessive delivery rates that we pay.

High electric rates are not only a problem for us as consumers, but also create a hurdle in the race to meet the state’s climate goals, which can only be met if we ditch fossil fuels and use renewably generated electricity to power our cars and homes. High electric rates make that transition less financially attractive.

As we work to stave off the worst impacts of climate change and accelerate a transition away from fossil fuels, it’s important that California aim to bring down electricity rates. Unfortunately, the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) is currently considering proposals that could make matters worse.

The proposals before the CPUC would all introduce a new fixed monthly charge tiered by income level, with higher-income households paying a fixed charge as high as $128 per month. Under the proposal submitted by the state’s three largest power companies, California households earning more than $180,000 a year would end up paying an average of $500 more per year for electricity than they do now.

The proposals come after the State Legislature approved and the Governor signed Assembly Bill 205 last year that mandates restructuring electricity pricing based on income. CALPIRG and Environment California oppose this pricing system, but given the legislative mandate, we will advocate for the CPUC to adopt the proposal that is least problematic for consumers and the environment.

Supporters of income-based fixed charges argue that high fixed charges are necessary to pay for wildfire preparedness, updates to the electrical grid, and the cost of electrification throughout the state. They argue that shifting more utility costs onto middle- and higher-income households will support the transition to electricity for low-income households.

While we share the goal of electrifying vehicles and buildings, imposing high fixed charges is a false solution. Analysis from the Clean Coalition and several utility experts demonstrates that high fixed charges improve the economics of electrification marginally at best; on the downside, such charges tend to encourage high consumption and waste, while punishing households that use less energy. Energy conservation is crucial to our ability to meet our climate goals, so proposals that punish those who conserve are in no one’s best interest.

To explain, we’ll start by taking a step back and look at how utility rates are traditionally designed. Then we’ll explain how a high fixed charge discourages energy conservation and why the proposed plan from the utilities does not make it more affordable for most Californians to electrify. Finally, we’ll look at alternative solutions to the problem of high electricity rates.

The basics of rate design: fixed and volumetric charges

To grasp the implication of proposals to impose high fixed charges on California utility customers, it’s important to understand the basics of how utility billing works – a construct known as “rate design.”

California is unique in not having fixed charges. Utilities in every other state have some form of them (though none tier their fixed charges by income – at least in part because such a plan could prove challenging to implement as utilities traditionally have no access to customer income levels). For residential customers, there are typically two types of charges on a monthly utility bill: fixed and volumetric.

- The fixed charge is a set monthly amount that every customer pays simply to be connected to the grid, regardless of how much or how little energy a customer uses.

- The volumetric charge is determined by applying a rate to the customer’s volume of consumption, measured in kilowatt hours (kWh): use more, pay more; use less, pay less.

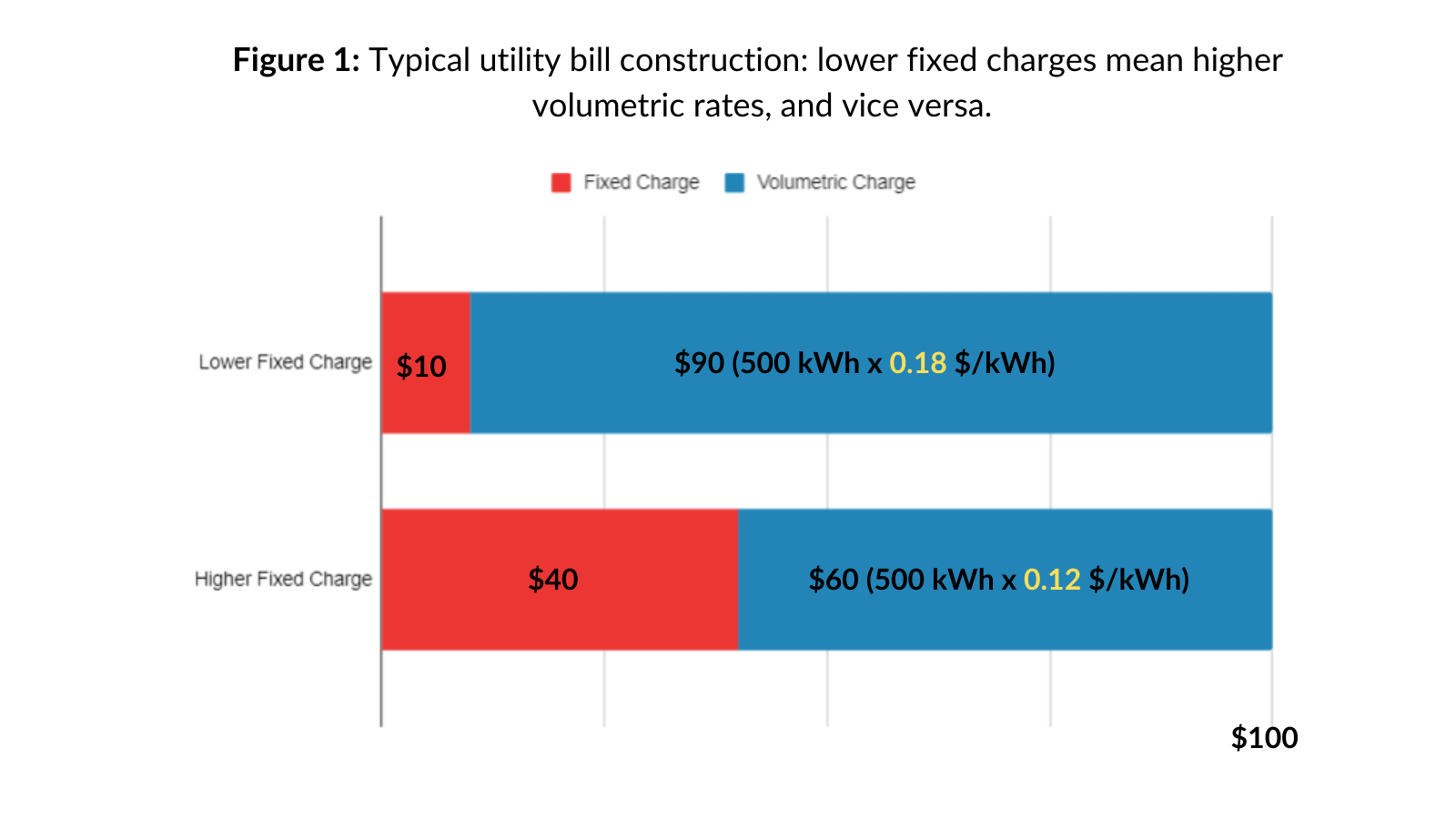

Utility regulation requires utilities to start with a target revenue for the year and then design the fixed charge and volumetric rate that, when applied to overall consumption estimates, add up to that target. That means that in a billing system that includes both types of charges, the level of one impacts the level of the other. A higher fixed charge will mean lower volumetric rates, and vice versa.

For illustration, imagine a utility where the average customer bill is $100 per month based on 500 kWh of average monthly consumption. With a $10 fixed charge, the volumetric rate would be $0.18 per kWh. In contrast, with a $40 fixed charge, the volumetric rate would be $0.12 per kWh.

Higher fixed charges benefit households that use more energy and punish households that use less

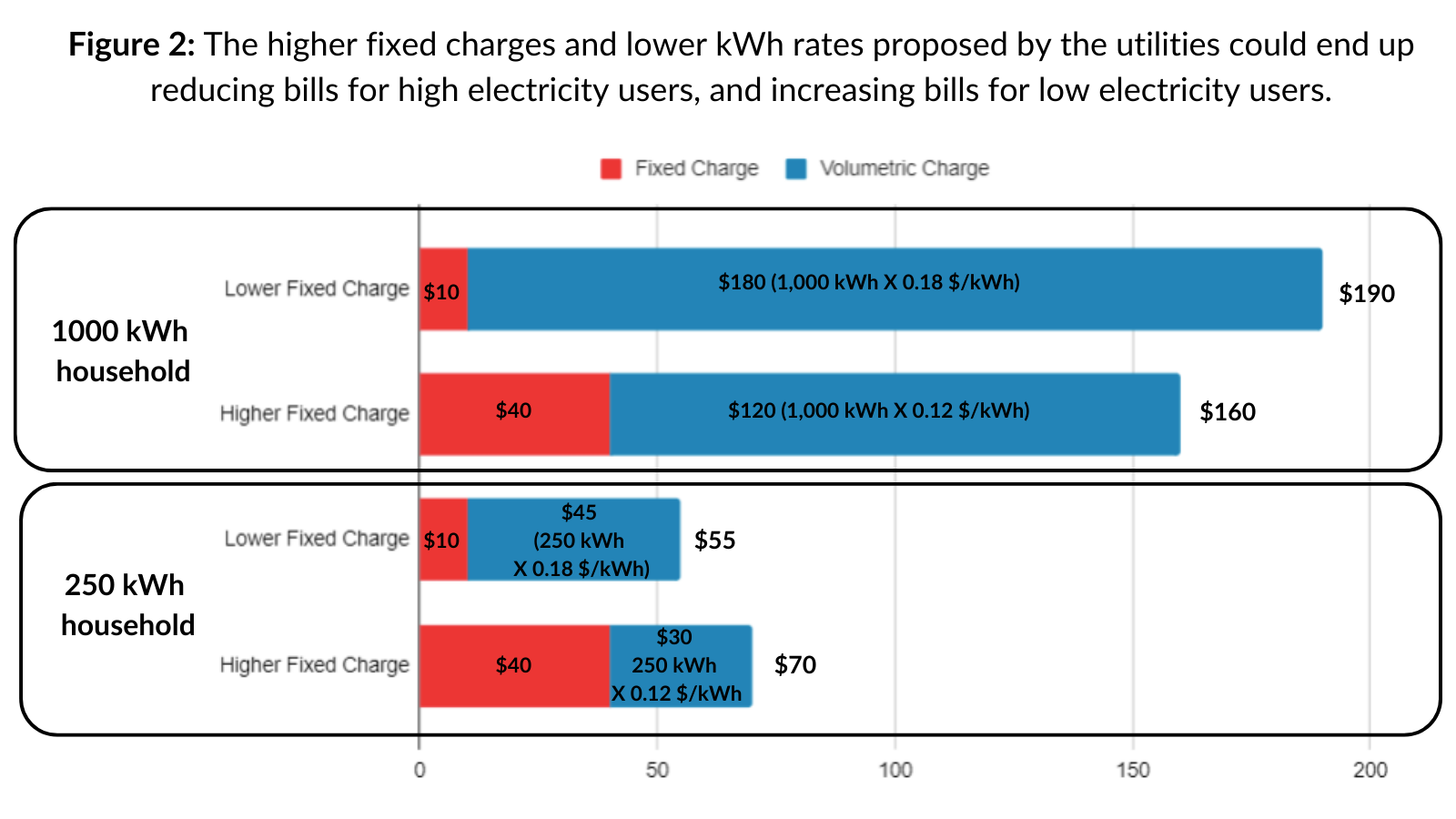

Consider the same two rate design scenarios featured above, and how they would affect two different households: one that uses more electricity than average, and one that uses less.

The higher fixed charge saves the higher energy consumption household $30 per month (with a $40 fixed charge they would pay a monthly bill of $160, while with a $10 fixed charge their total bill would be $190). That same higher fixed charge costs the household using ¼ as much energy $15 more per month (with a monthly bill of $70 using a $40 fixed charge vs $55 with a $10 fixed charge).

By shifting costs from higher to lower energy consumption households, the higher fixed charge results in the lower energy consumption household subsidizing the higher consumption household.

Who lives in these low consumption households? Apartment dwellers, owners of small homes, and families who spent thousands of dollars to make their homes energy-efficient or tens of thousands to install solar panels on their roof to help abate the climate crisis (with the state’s assurance that they would recoup their investment over time).

High fixed charges will discourage investments in energy efficiency and rooftop solar

In utility proceedings across the country, consumer and environmental advocates regularly argue with utilities over the size of fixed charges.

Typically, utilities argue for higher fixed charges because such charges produce a dependable, consistent stream of revenue that won’t fluctuate with usage patterns, thus making it easier for these companies to hit their profit targets. A cool summer with less reliance on air conditioning, for example, has less effect on utility revenues if a high fixed charge is in place.

Consumer and environmental advocates, on the other hand, typically argue for lower fixed charges because lower fixed charges, and the corresponding higher volumetric rates, incentivize energy efficiency, conservation, and rooftop solar, and discourage energy waste.

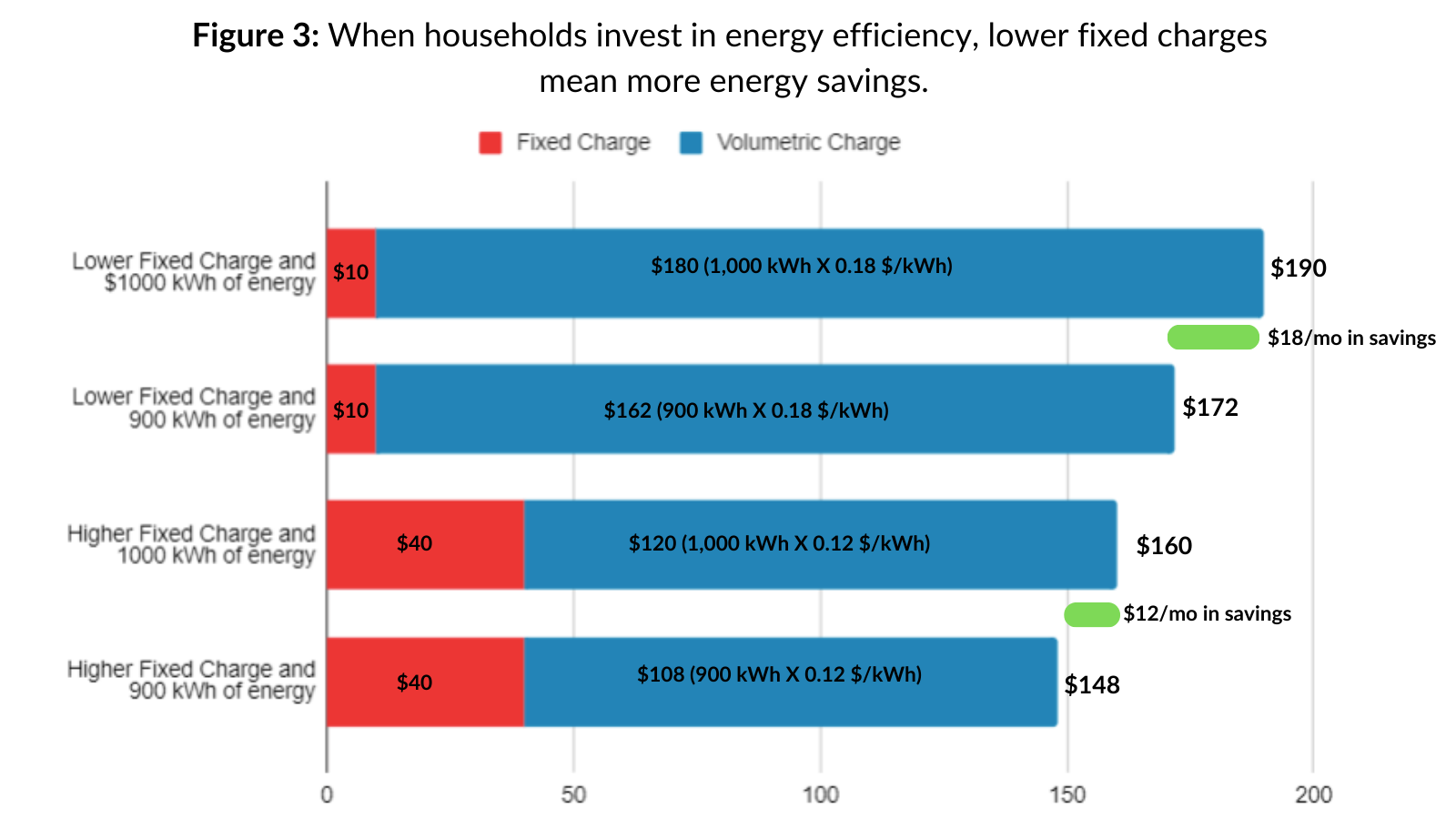

Here’s an example: let’s say your household consumes 1000kWh of energy, like the one in the chart above. If you needed to replace a major appliance, you might decide to pay more up front for a highly efficient appliance on the assumption that over time, monthly savings on utility bills will recoup that original higher cost and start saving you money. Let’s say the new appliance reduces your overall energy usage by 10%. The chart below shows that with a $10 fixed charge and 10% less energy usage, your monthly bill would go down $18, from $190 per month to $172. In contrast, with a $40 fixed charge, your monthly bill would go down only $12, from $160 to $148.

The difference of $6 per month may not seem like a lot, but that’s $72 per year and differences like it can add years to the payback period for a more efficient appliance, discouraging people from buying them. The exact same calculation applies to rooftop solar: higher fixed rates lengthen the payback period and discourage investment. As fifteen utility experts put it in a letter to the CPUC, “Efficiency and frugality will be penalized and inefficiency and waste will be rewarded, in a reversal of the state’s long-standing tradition of promoting efficient energy use.”

These differences have critical implications beyond our wallets. One of the key drivers of the overall cost of the electric grid is the need to ensure that the grid can meet peak demand – times when collective consumption of electricity is highest. When a household gets more efficient, that home requires less energy at peak, which means lower costs for the entire system, which benefits all customers. Beyond that, for as long as energy production continues to contribute to climate and air pollution, lower consumption further benefits the public and environment.

Rate structure should incentivize lower consumption. That’s what lower fixed charges, paired with higher volumetric charges, do.

Income-based charges with high fixed charges will not help the state electrify

Some California environmental and consumer advocates have joined utilities to rally behind income-based fixed charges with high fixed charges as a solution to the negative impact of high rates on the climate-imperative transition to electricity.

They argue:

- Introducing a fixed charge will allow utilities to lower volumetric rates. That will help consumers as they increase their electricity usage by switching to electric appliances and vehicles.

- A variable fixed charge – higher for wealthier households and lower for the less wealthy – will reduce costs for low-income households and allow them to pursue electrification as well.

Unfortunately, analysis presented by the Clean Coalition shows that the major, high-fixed-charge proposals before the CPUC fail to meaningfully improve the economics of electrification, while rewarding the biggest energy users and punishing efficient and low-consumption households.

According to the analysis, none of the proposals would deliver savings through electrification for the lowest-income households, those on the CARE program. For non-CARE households, none of the high fixed charge proposals would improve the economics of electrification for customers who are currently using modern, high-efficiency gas appliances. When the comparison is made for non-CARE customers using older, lower-efficiency gas appliances, some households in one utility service territory could achieve marginal savings through electrification.

The analysis also shows that, if implemented, the proposals would immediately and significantly benefit high-consumption households. As the Clean Coalition wrote to the Commission, “the real winners are inefficient properties with high consumption patterns.”

High fixed-charge systems provide a perverse incentive for users to consume more electricity. And from there it just gets worse. The more electricity we consume, the more expensive it becomes to expand and maintain the energy grid. And the more electricity we consume, the harder and more expensive it is to replace dirty energy sources with clean ones.

Better solutions are available

Rate design is a system for allocating the costs of an electricity system across its users. The chosen design should direct electricity users’ behavior in ways that are consistent with the state’s goals. It should also do as much as possible to limit the high costs of electricity delivery in California.

Fixed charges based on income do not meet those standards. They simply shift the burden among ratepayers, creating zero incentive for the utilities to reduce costs. As utility expert Jim Lazar writes, California could pursue a number of other policies to better address excessive rates, such as lowering utility profit levels, which are higher than profits rates across the country (which are also arguably too high), among others. Additionally, by supporting an expansion of rooftop solar and battery storage, the state could reduce utilities’ need to spend on long-distance power lines and other large-scale grid infrastructure. And just within the realm of rate design, both Lazar and the Clean Coalition argue that well-designed time-of-use rates (where users pay more during peak energy demand hours) better improve the economics of electrification without incentivizing energy waste.

The CPUC, however, is bound by Assembly Bill 205 to implement a fixed charge, and to include at least three tiers based on income. Of the proposals before the CPUC, the Clean Coalition’s proposal for modest fixed charges is the best: a $0 fixed charge for the lowest income customers on the state’s California Alternative Rates for Energy (CARE) program, $5 for other low-income customers (Family Electric Rates Assistance Program), and modest fixed charges, none more than $19, for everyone else. Not only does this proposal keep fixed charges modest, it also won’t require utilities to get any additional income information from California residents, which could prove challenging.

If California wishes to prioritize finding more ways to help low-income households pay their energy bills, it should use tools that don’t incentivize energy waste. California already has an assistance program, whereby low-income customers get a 35% discount on their bill; the state could always consider improvements to that program.

The only path to a cleaner, more durable and more affordable energy system is to cut energy waste and lower consumption through energy efficiency and conservation. Resigning ourselves to a high-cost, high-consumption system is a move in the wrong direction.

Topics

Authors

Jenn Engstrom

State Director, CALPIRG

Jenn directs CALPIRG’s advocacy efforts, and is a leading voice in Sacramento and across the state on protecting public health, consumer protections and defending our democracy. Jenn has served on the CALPIRG board for the past two years before stepping into her current role. Most recently, as the deputy national director for the Student PIRGs, she helped run our national effort to mobilize hundreds of thousands of students to vote. She led CALPIRG’s organizing team for years and managed our citizen outreach offices across the state, running campaigns to ban single-use plastic bags, stop the overuse of antibiotics, and go 100% renewable energy. Jenn lives in Los Angeles, where she enjoys spending time at the beach and visiting the many amazing restaurants in her city.

Laura Deehan

State Director, Environment California

Laura directs Environment California's work to tackle global warming, protect the ocean and fight for clean air, clean water, open spaces and a livable planet. Laura stepped into the State Director role in January, 2021 and has been on staff for over twenty years. She has led campaigns to make sure California goes big on offshore wind and to get lead out of school drinking water. As the Environment California Field Director, she worked to get California to go solar, ban single use plastic grocery bags and get on track for 100% clean energy. Laura lives with her family in Richmond, California where she enjoys hiking, yoga and baking.

Find Out More

Rooftop Solar at Risk

“Certified natural gas” is not a source of clean energy

How you can electrify your home