Highway Boondoggles 2

More Wasted Money and America's Transportation Future

Twelve proposed highway projects across the country – slated to cost at least $24 billion – exemplify the need for a fresh approach to transportation spending. These projects, some originally proposed decades ago, are either intended to address problems that do not exist or have serious negative impacts on surrounding communities that undercut their value.

Downloads

America is in a long-term transportation funding crisis. Our roads, bridges and transit systems are falling into disrepair. Demand for public transportation, as well as safe bicycle and pedestrian routes, is growing. Traditional sources of transportation revenue, especially the gas tax, are not keeping pace with the needs. Even with the recent passage of a five-year federal transportation bill, the future of transportation funding remains uncertain.

Twelve proposed highway projects across the country – slated to cost at least $24 billion – exemplify the need for a fresh approach to transportation spending. These projects, some originally proposed decades ago, are either intended to address problems that do not exist or have serious negative impacts on surrounding communities that undercut their value. They are but a sampling of many questionable highway projects nationwide that could cost taxpayers tens of billions of dollars to build, and many more billions over the course of upcoming decades to maintain.

America does not have the luxury of wasting tens of billions of dollars on new highways of questionable value. State and federal decision-makers should reevaluate the need for the projects profiled in this report and others that no longer make sense in an era of changing transportation needs. State decision-makers should use the flexibility provided in the new federal Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act (FAST Act) to focus investment on real transportation solutions, including repairing potholes and bridges and investing in public transportation and bicycling and walking options.

Americans’ transportation needs are changing. America’s transportation spending priorities aren’t.

- State governments continue to spend billions on highway expansion projects that fail to solve congestion.

- In Texas, for example, a $2.8 billion project widened Houston’s Katy Freeway to 26 lanes, making it the widest freeway in the world. But commutes got longer after its 2012 opening: By 2014 morning commuters were spending 30 percent more time in their cars, and afternoon commuters 55 percent more time.

- A $1 billion widening of I-405 in Los Angeles that disrupted commutes for five years – including two complete shutdowns of a 10-mile stretch of one of the nation’s busiest highways – had no demonstrable success in reducing congestion. Just five months after the widened road reopened in 2014, the rush-hour trip took longer than it had while construction was still ongoing.

- Highway expansion saddles future generations with expensive maintenance needs, at a time when America’s existing highways are already crumbling.

- Between 2009 and 2011, states spent $20.4 billion annually for expansion or construction projects totaling 1 percent of the country’s road miles, according to Smart Growth America and Taxpayers for Common Sense. During the same period, they spent just $16.5 billion on repair and preservation of existing highways, which are the other 99 percent of American roads.

- According to the Federal Highway Administration, the United States added more lane-miles of roads between 2005 and 2013 – a period in which per-capita driving declined – than in the two decades between 1984 and 2004.

- Federal, state and local governments spent roughly as much money on highway expansion projects in 2010 as they did a decade earlier, despite lower per-capita driving.

- Americans’ long-term travel needs are changing.

- In 2014, transit ridership in the U.S. hit its highest point since 1956. And recent years have seen the emergence of new forms of mobility such as carsharing, bikesharing and ridesharing whose influence is just beginning to be felt.

- According to an Urban Land Institute study in 2015, more than half of Americans – and nearly two-thirds of Millennials, the country’s largest generation – want to live “in a place where they do not need to use a car very often.” Young Americans drove 23 percent fewer miles on average in 2009 than they did in 2001.

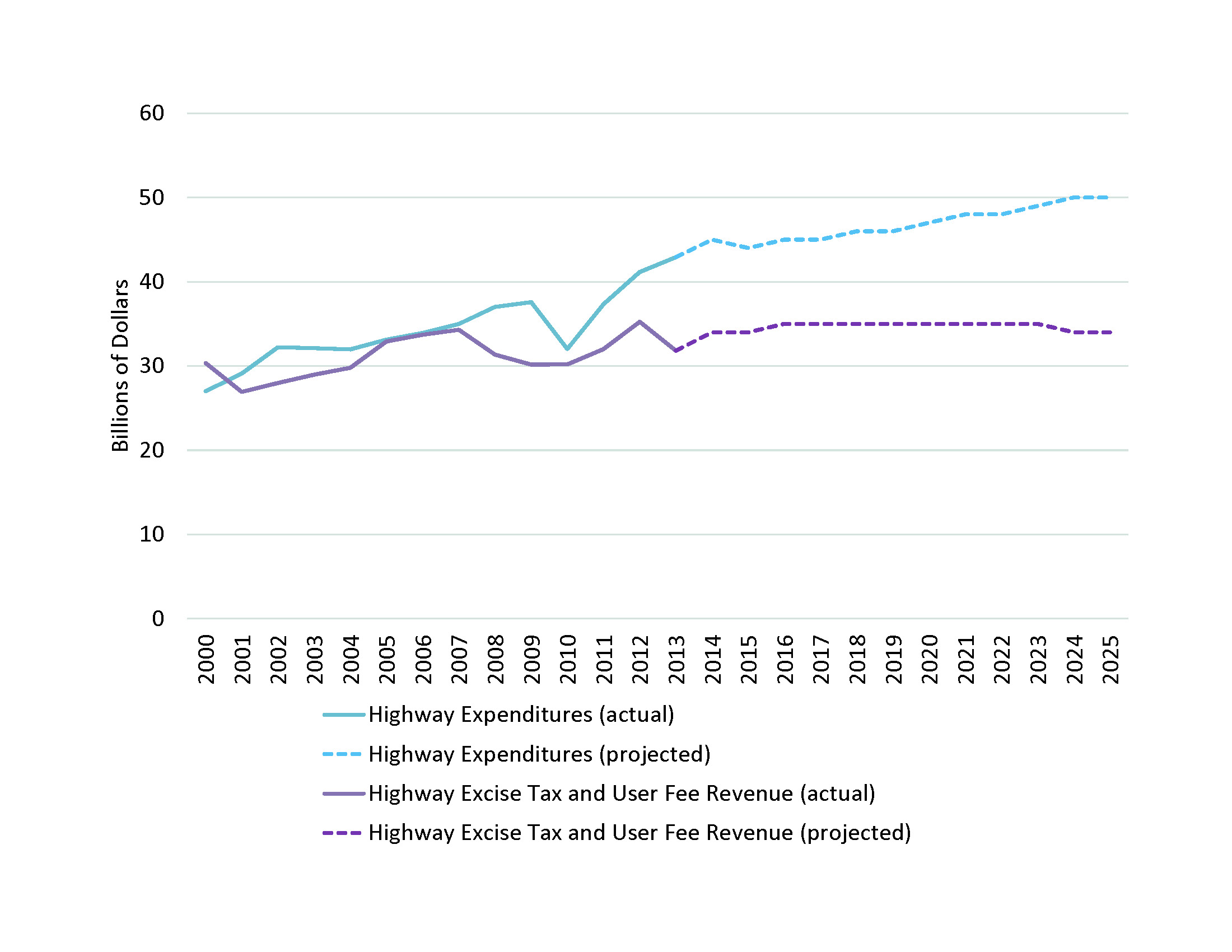

The Federal Highway Trust Fund and many state transportation funds are increasingly dependent on the failing gas tax and infusions of general fund spending to sustain transportation investments.

- The Federal Highway Trust Fund – once supported entirely by the gas tax – has been subsidized from general tax revenues since the late 2000s. Federal highway spending is projected to exceed revenues in every year through 2025, according to Congressional Budget Office projections. (See Figure ES-1.) The FAST Act transportation bill approved in December 2015 transfers an additional $70 billion from the country’s general funds to the Highway Trust Fund.

- Bailing out the Highway Trust Fund with general government funds cost $65 billion between 2008 and 2014, including $22 billion in 2014 alone. Making up the projected shortfall through 2025 would cost an additional $147 billion.

States continue to spend tens of billions of dollars on new or expanded highways that are often not justified in terms of their benefits to the transportation system, or that pose serious harm to surrounding communities. In some cases, officials are proposing to tack expensive highway expansions onto necessary repair and reconstruction projects, while other projects represent entirely new construction. Many of these projects began or were first proposed years or decades ago, are based on long-outdated data, and have continued moving forward with no re-evaluation of their necessity or benefits.

Questionable projects poised to absorb billions of scarce transportation dollars include:

- I-95 widening, Connecticut, $11.2 billion – Widening the highway across the entire state of Connecticut would do little to solve congestion along one of the nation’s most high-intensity travel corridors.

- Tampa Bay Express Lanes, Florida, $3.3 billion – State officials admit that a decades-old plan to construct toll lanes would not solve the region’s problems with congestion, while displacing critical community job-training and recreational facilities.

- State Highway 45 Southwest, Texas, $109 million – Building a new, four-mile, four-lane toll road would increase traffic on one of the most congested highways in Austin, and increase water pollution in an environmentally sensitive area critical for recharging an aquifer that provides drinking water to 2 million Texans.

- San Gabriel Valley Route 710 tunnel, California, $3.2 billion to $5.6 billion – State officials are considering the most expensive, most polluting and least effective option for addressing the area’s transportation problems: a double bore tunnel.

- I-70 East widening, Colorado, $58 million – While replacing a crumbling viaduct that needs to be addressed, Colorado proposes wasting millions of dollars widening the road and increasing pollution in the surrounding community.

- I-77 Express Lanes, North Carolina, $647 million – A project that state criteria say does not merit funding is moving forward because a private company is willing to contribute; taxpayers will still be on the hook for hundreds of millions of dollars.

- Puget Sound Gateway, Washington, $2.8 billion to $3.1 billion – The state is proposing to spend billions of dollars on a highway to relieve congestion in an area where traffic has not grown for more than a decade, and where other pressing needs for transportation funding exist.

- State Highway 249 extension, Texas, $337 million to $389 million – The Texas Department of Transportation relies on outdated traffic projections to justify building a 30-mile six-lane highway through an area already suffering from air quality problems.

- U.S. 20 widening, Iowa, $286 million – Hundreds of millions of dollars that could pay for much-needed repairs to existing roads are being diverted to widen a road that does not need expansion to handle future traffic.

- Paseo del Volcan extension, New Mexico, $96 million – A major landholder is hoping to get taxpayer funding to build a road that would open thousands of acres of desert to sprawling development.

- Portsmouth bypass, Ohio, $429 million – Despite roads across Ohio being in dire need of repair, the state Department of Transportation is embarking upon its most expensive project ever: building a new road to bypass a 20,000-person city where driving is decreasing.

- Mon-Fayette Expressway extension, Pennsylvania, $1.7 billion – A new toll road long criticized because it would damage communities is moving forward in an area where residents are calling instead for repairs to existing roads and investment in transit improvements.

Several states are re-evaluating the wisdom of boondoggle highway projects – either shelving them entirely or forcing revisions to the projects.

- The Illiana Expressway was a proposed $1.3 billion to $2.8 billion tollway intended to stretch from I-55 in Illinois to I-65 in Indiana. Faced with a budget deficit, Illinois Governor Bruce Rauner suspended the project in January 2015 pending a review; in a lawsuit filed in May 2015, a coalition of environmental advocacy groups said the road’s federal approval had been based on bad population and financial projections, and did not properly consider the potential environmental damage. In June 2015, a federal judge agreed, and invalidated the Federal Highway Administration’s approval of the project.

- The Trinity Parkway in Dallas was once a $1.5 billion proposal to build a six-lane, nine-mile tolled highway along the river in the middle of the city. Under fire from the community, including people who had first conceived of the road project, the city council voted unanimously in August 2015 to limit city spending to a reduced version of the project, a four-lane highway without tolls. It is still unclear, however, whether the smaller highway will alleviate the concerns raised by the original proposal.

- A proposal to widen I-94 in Milwaukee has been denied funding by state lawmakers in the wake of community advocacy opposing the project. An analysis by a group called 1000 Friends of Wisconsin found the state Department of Transportation systematically overestimates traffic projections. WISPIRG Foundation has proposed improving the area’s mobility with more effective and less costly options that state officials ignored.

- An extension to an existing toll road in southern California was denied on the grounds that it, and a future additional extension, would threaten local water resources. Other toll roads in the region have failed to attract enough traffic to meet revenue expectations, and data suggest traffic is not growing as quickly as officials had projected.

The diversion of funds to highway boondoggle projects is especially harmful given that there is an enormous need for investment in repairs to existing roads, as well as transit improvements and investments in bicycling and pedestrian infrastructure. Federal and state governments should eliminate or downsize unnecessary or low-priority highway projects to free up resources for true transportation priorities. Under existing federal funding guidelines, they have the flexibility to do this with little or no need for additional approval.

Specifically, policymakers should:

- Invest in transportation solutions that address congestion more cheaply and effectively than highway expansion. Investments in public transportation, changes in land-use policy, road pricing measures, and technological measures that help drivers avoid peak-time traffic, for instance, can reduce the need for costly and disruptive highway expansion projects.

- Adopt fix-it-first policies that reorient transportation funding away from highway expansion and toward repair of existing roads and investment in other transportation options. As first suggested by Smart Growth America and Taxpayers for Common Sense, this includes more closely tying states’ allocations of federal transportation funding to infrastructure conditions, encouraging states to ensure existing roads and bridges are properly maintained before using funds for new construction or expansion projects. To most effectively meet this goal, government agencies should provide greater public transparency about spending plans, including an accounting of future maintenance expenses.

- Give priority funding to transportation projects that reduce growth in vehicle-miles traveled, to account for the public health, environmental and global warming benefits resulting from reduced driving.

- Analyze the need for projects using the most recent data and up-to-date transportation system models. Planning should include full cost-benefit analyses, including the costs to maintain newly constructed highways. Models should reflect a range of potential future trends for housing and transportation, incorporate the availability of new transportation options (such as carsharing, bikesharing and ridesharing), and include consideration of transit options. Just because a project has been in the planning pipeline for several years does not mean it deserves to receive scarce taxpayer dollars.

- Apply the same scrutiny to public-private partnerships as to those funded solely by taxpayers.

- Revise transportation forecasting models to ensure that all evaluations of proposed projects use up-to-date travel information.

- Invest in research and data collection to better track and react to ongoing shifts in how people travel.

CLARIFICATION: The original version of this report states that, under the terms of the contract between the private developer of North Carolina’s I-77 Express Lanes project and the state of North Carolina, the state must compensate the developer in the event that new transportation projects are built that might divert traffic away from the toll lanes. The contract does require the state to compensate the private operator in the event that toll revenues fall short of specific thresholds, a possible result of expanding transportation infrastructure elsewhere. However, the construction of new transportation infrastructure does not, in and of itself, appear to trigger a compensation event.

Topics

Find Out More

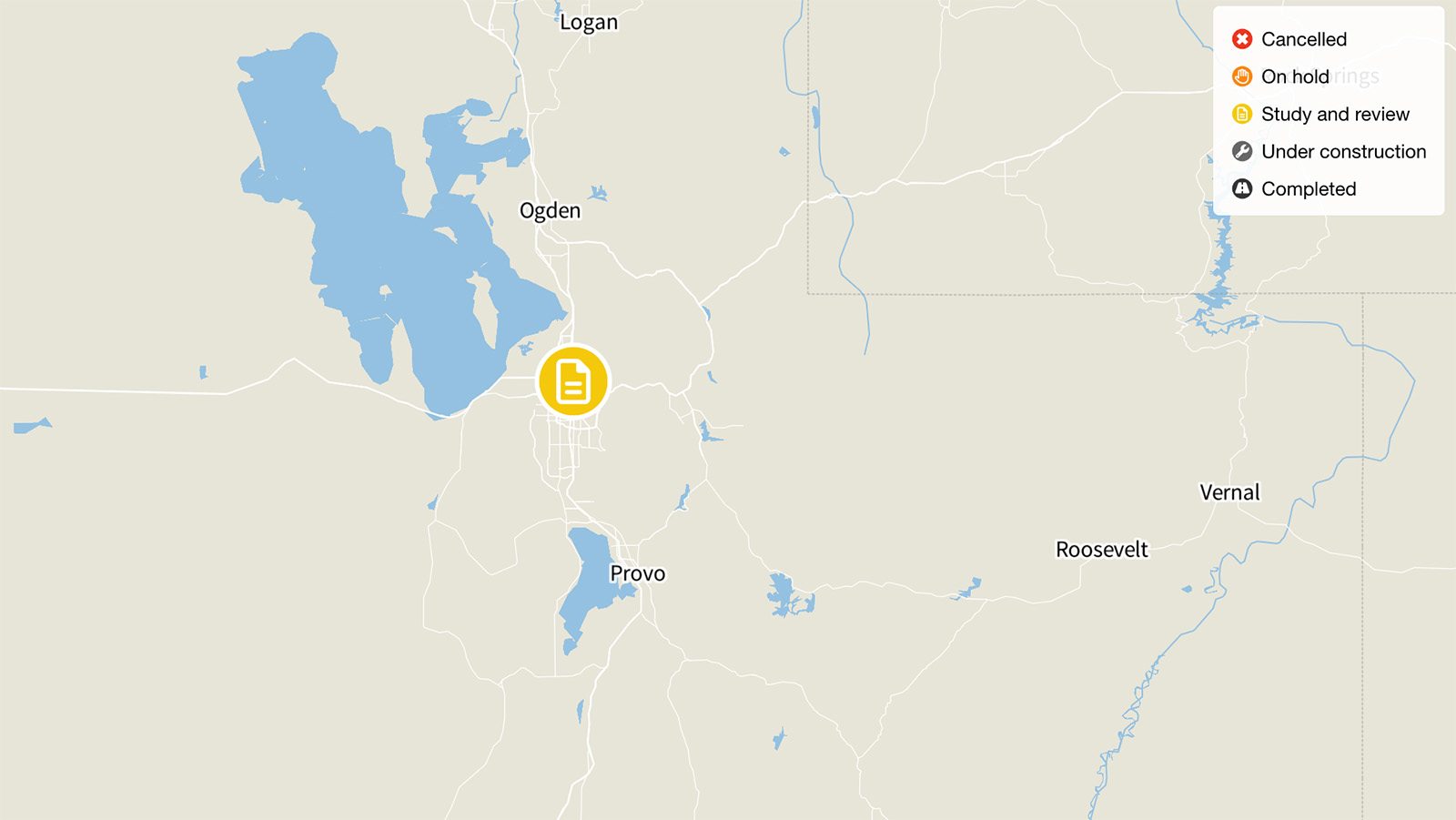

I-15 Expansion, Salt Lake City

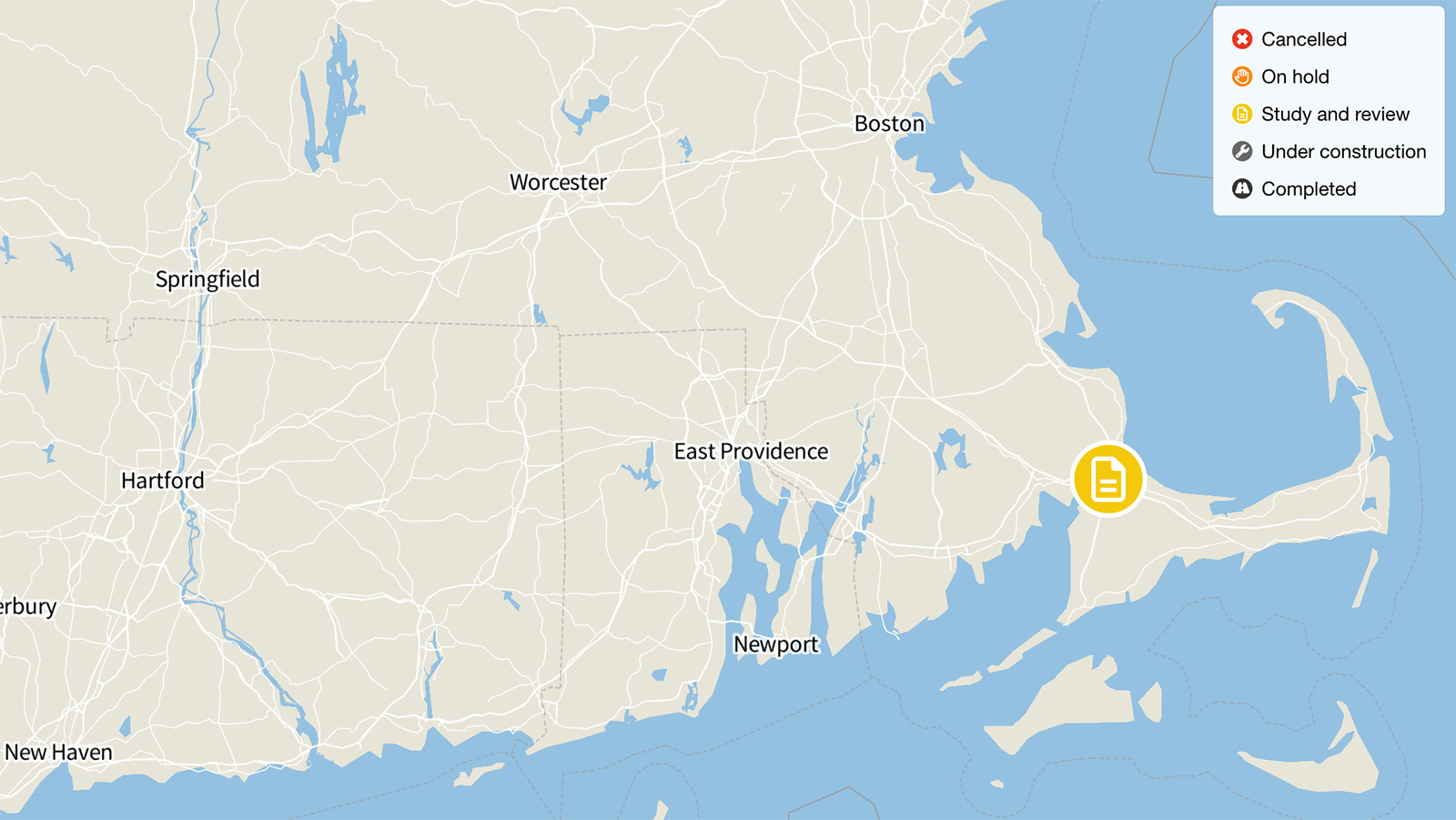

The Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, New York