Kevin O'Reilly

Former Director, Campaign for the Right to Repair, U.S. PIRG Education Fund

When it comes to fixing farm equipment, farmers have to turn to the dealership for many repairs because dealership technicians can access software tools that farmers can’t. That can lead to high costs and long repair delays that can put farmers’ crops and livelihoods at risk. Dealership consolidation — particularly by John Deere — magnifies these problems by further eroding repair choices for farmers. We researched just how big the consolidation problem is and how Right to Repair could immediately and dramatically expand repair choices for farmers.

Former Director, Campaign for the Right to Repair, U.S. PIRG Education Fund

When it comes to fixing farm equipment, farmers have to turn to the dealership for many repairs because dealership technicians can access software tools that farmers can’t. That can lead to high costs and long repair delays that can put farmers’ crops and livelihoods at risk. Dealership consolidation — particularly by John Deere — magnifies these problems by further eroding repair choices for farmers. We researched just how big the consolidation problem is and how Right to Repair could immediately and dramatically expand repair choices for farmers.

“When you look up an error code online, it tells you 30 different things that could be wrong. It could be the injector plug, it could be a failed sensor, it could be that the Diesel Emissions Fluid pump is not putting out. With software, the dealer can see specifically which one of those pieces is the issue. But because I can’t get that software, I have to chase parts, throwing money at the problem and replacing things until the problem goes away. Sometimes it’s just a software problem—you just need to go and reset it. I can’t do that.” - Minnesota farmer Wyatt Parks

Photo by TPIN | TPIN

“Even if [John Deere] continues to have this repair monopoly, if they had some segmentation, it would provide some incentive for these dealerships to do a better job. The fact that they have consolidated so much means that they absolutely don’t have to at all because you just have no other choice.” - Missouri farmer Jared Wilson

Photo by TPIN | TPIN

“When I first started farming, there were three family-owned dealerships within 45 minutes of my ranch. Now I have to drive nearly four hours to get to a second dealership chain.” - Walter Schweitzer, a third-generation farmer and president of the Montana Farmers Union

Photo by TPIN | TPIN

“I don’t like the idea that we just can’t do anything for ourselves, and we have to rely on mom and dad and big corporate America to make it all better and tuck us in at night.” - Minnesota farmer Wyatt Parks

Photo by TPIN | TPIN

1of 4

Farmers and ranchers rely on equipment such as tractors and combine harvesters to produce America’s food supply. Over the years, that equipment has gotten bigger, more expensive and more digital. The software integrated in modern tractors, ostensibly created to make farm operations more efficient, can be used by manufacturers to lock farmers out of fixing their own equipment.

If tractors were like cars, farmers would be able to choose between fixing their equipment themselves, hiring an independent mechanic to do it for them, or driving to the dealer. That is because 86% of Massachusetts voters approved an automotive Right to Repair ballot measure that was eventually adopted by the industry nationwide. This law, on which farmers and advocates modeled Agricultural Right to Repair legislation, requires auto manufacturers to provide car owners and independent repair shops with access to necessary repair materials.

But no Right to Repair law exists for agricultural equipment. That means some necessary software tools are not available to farmers, independent repair mechanics, or anyone who is not manufacturer-approved.

Therefore, farmers must turn to dealer technicians for certain repairs, as these are the only parties that can get access to necessary software repair tools. Forced dealer service can cause farmers to face long delays and high repair costs when their equipment breaks down. When a tractor malfunctions during planting, harvest or threatening weather, a farmer’s crop and livelihood can hang in the balance.

This repair monopoly makes local dealerships incredibly important to a farmer’s operation. But these dealerships are dwindling. According to the survey conducted by U.S. PIRG Education Fund and National Farmers Union, 65% of the 74 farmers who responded report having access to fewer dealerships than five years ago. At the same time, many farmers report that local mom and pop dealers were bought by larger chains, resulting in the consolidation confirmed in our findings.

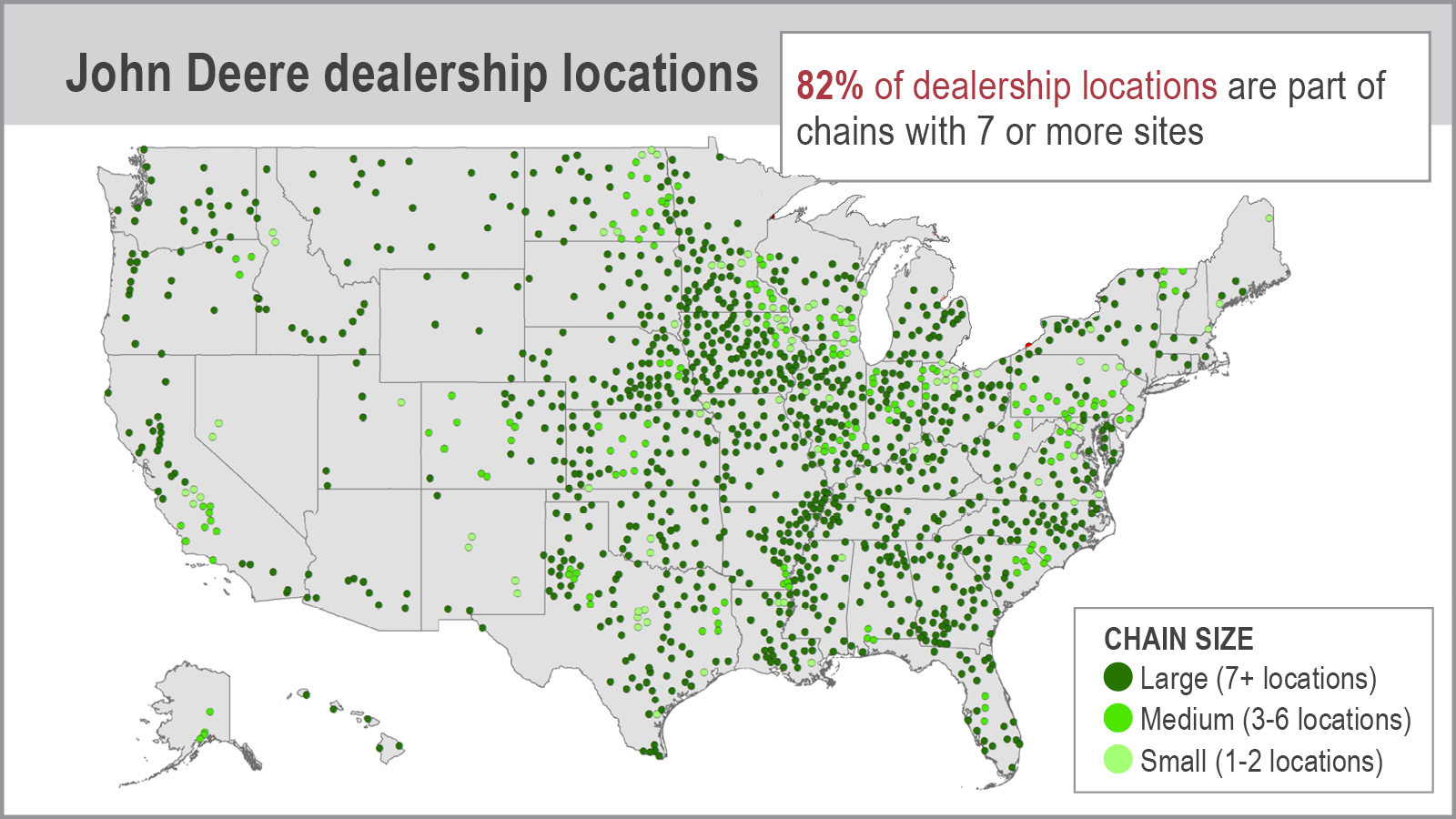

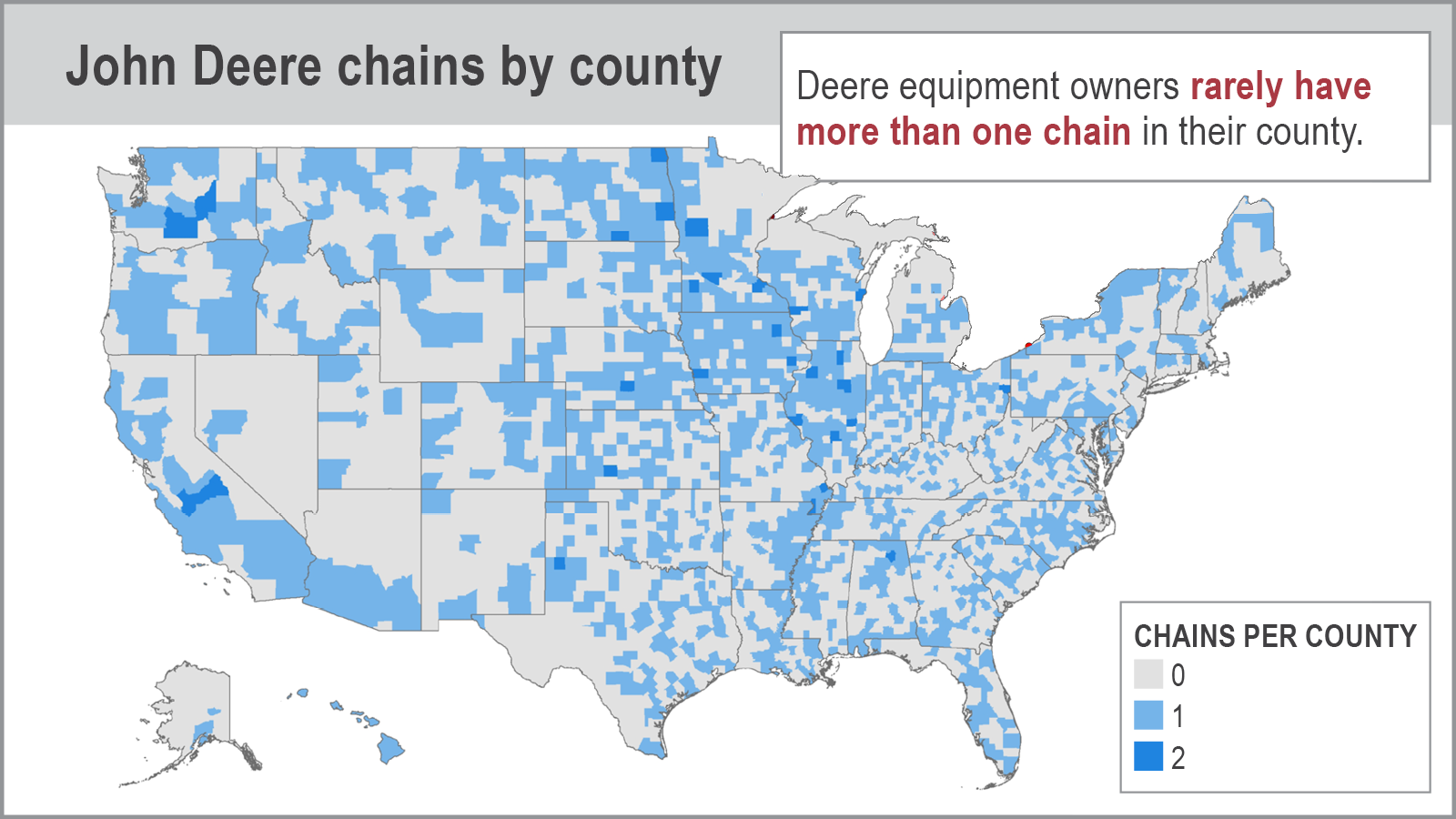

John Deere, which controls 53% of the country’s large tractor market, has been working to consolidate dealerships since the mid-2000s. Our research shows Deere has been quite successful in consolidating dealerships: 82% of Deere’s 1,357 agricultural equipment dealerships are a part of a large chain with seven or more locations. The average Deere chain has about 8 sites, with the largest chain network including 67. This mass consolidation means that there is one John Deere dealership chain for every 12,018 farms and every 5.3 million acres of American farmland.

Particular chain dealership networks often dominate certain regions in states, meaning that some farmers only have one dealership choice near them. That can force them to travel long distances and cross state lines to get another quote from a dealer they might trust more.

Montana offers a stark example of the regional domination of certain Deere dealerships. Despite having 58 million acres of farmland, the second-most of any state in the country, the state only has three large John Deere chains with a combined 19 locations serving Montana farms. RDO Equipment has a couple locations in western Montana, Frontline Ag Solutions serves much of the center of the state and C & B Operations has locations throughout eastern Montana.

When I first started farming, there were three family-owned dealerships within 45 minutes of my ranch. Now I have to drive nearly four hours to get to a second dealership chain… I just don’t get the same service that I used to.Walter Schweitzer

Third-generation farmer and president of the Montana Farmers Union

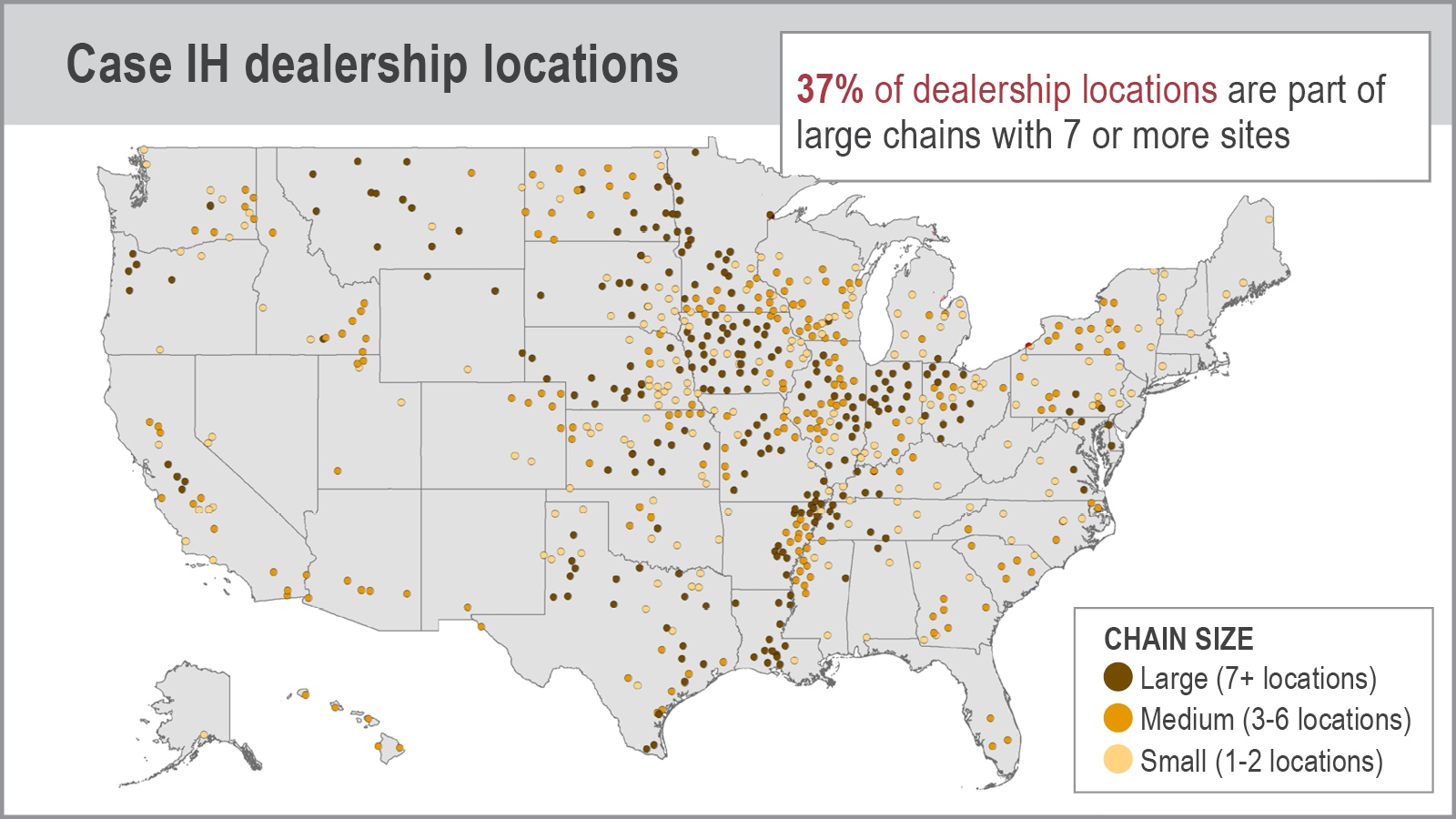

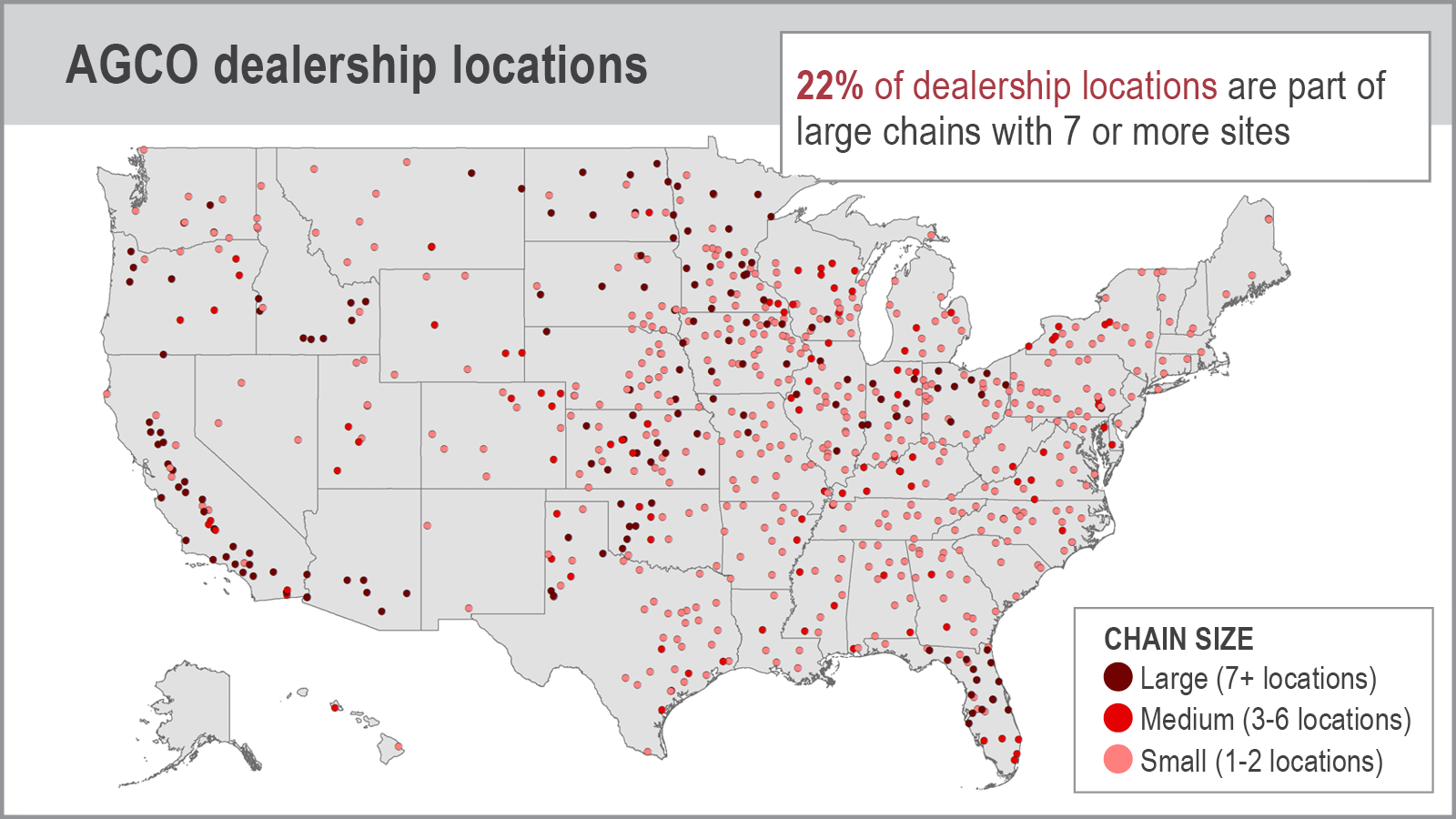

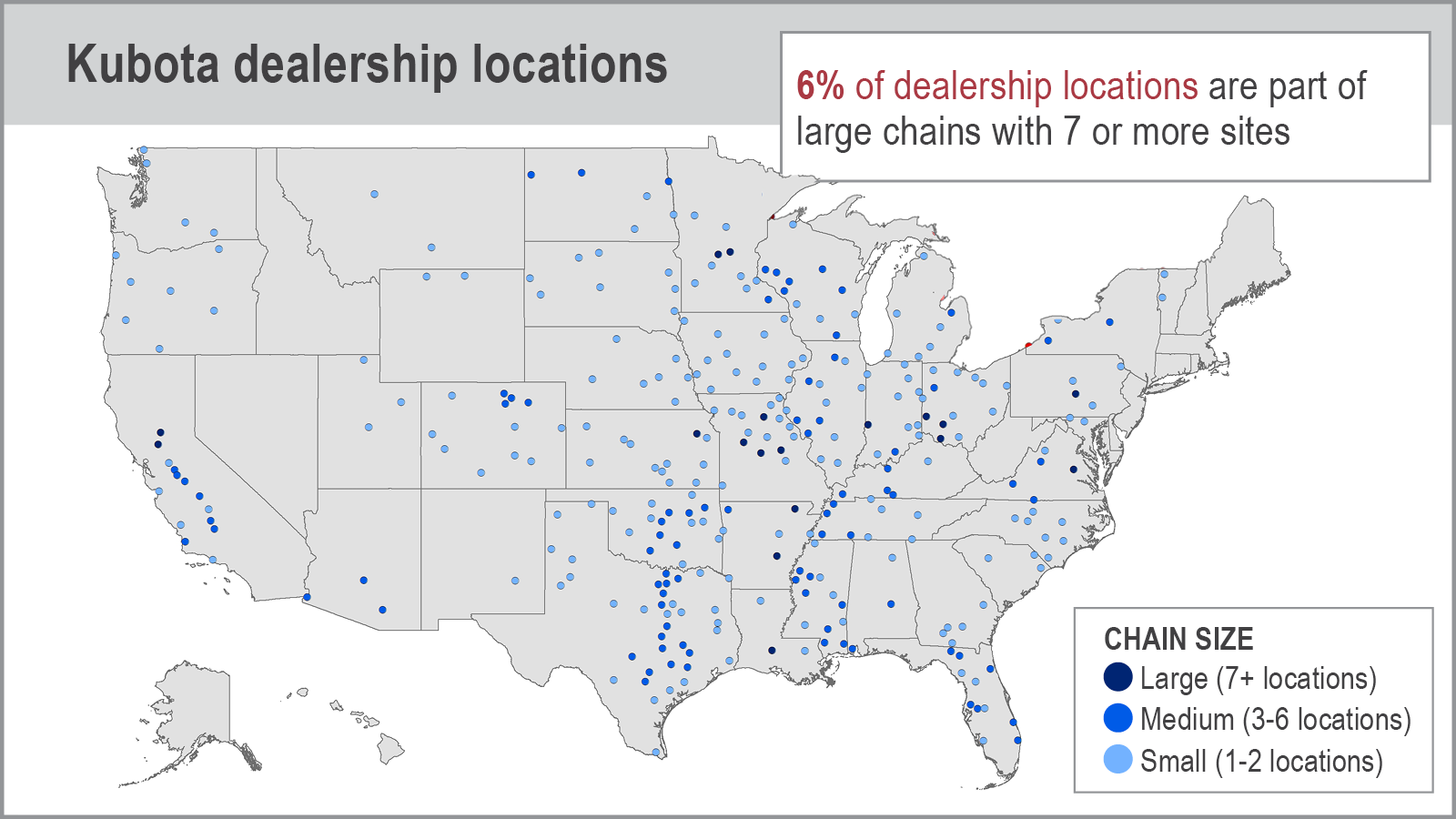

While less pronounced for other manufacturers, large dealership chains can be a problem for farmers regardless of the color of the paint on their tractor. The largest Case IH chain includes 57 locations that service agricultural equipment, AGCO includes 31, and the chain with the most locations that services Kubota equipment has 6 sites.

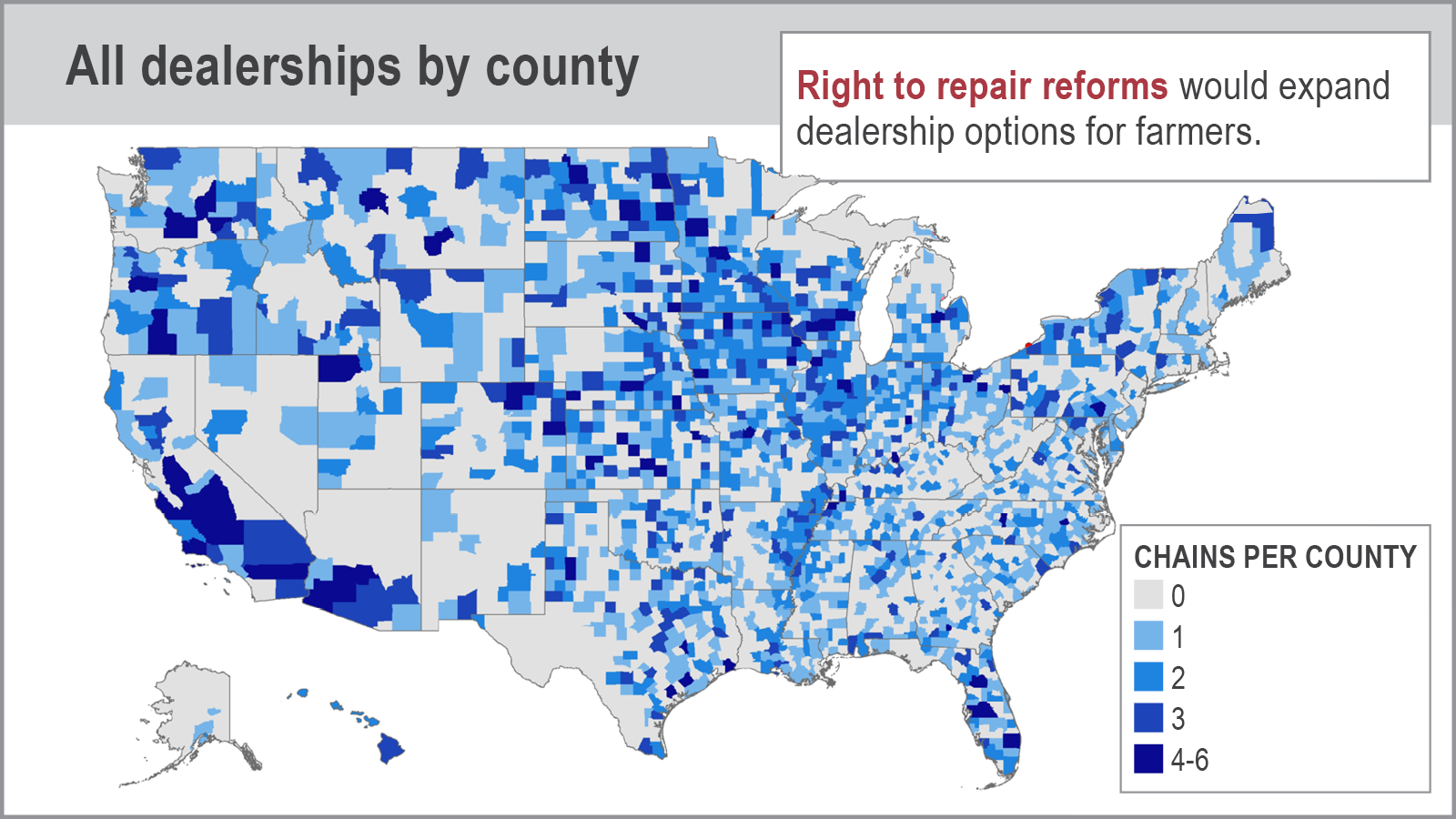

Dealer-manufacturer exclusivity is connected to and compounds this problem. Ninety-five percent of the combined 2,942 John Deere, Kubota, Case IH and AGCO dealership locations across the country service agricultural equipment from only one of the four manufacturers. Repair restrictions require dealerships to maintain agreements with manufacturers in order to access repair materials. If these restrictions were removed, dealerships, like farmers, could buy the tools they need to fix equipment made by any manufacturer. But as it is now, repair-infrastructure remains locked down as consolidation limits choice for farmers.

Some farmers have good working relationships with their dealership regardless of the size of the chain to which it belongs. But many indicate that customer service at chain dealerships can be much worse than at local dealerships.

“When I first started farming, there were three family-owned dealerships within 45 minutes of my ranch. You’d walk in and one of the family members was behind the counter,” said Walter Schweitzer, a third-generation farmer and president of the Montana Farmers Union. “They went out of their way to help me because they had a vested interest in doing so — they didn’t want to lose my business to one of their nearby competitors.

“Now I have to drive nearly four hours to get to a second dealership chain, where there’s a corporate employee working. Between the lack of competition and the lack of local connection, I just don’t get the same service that I used to,” Schweitzer said.

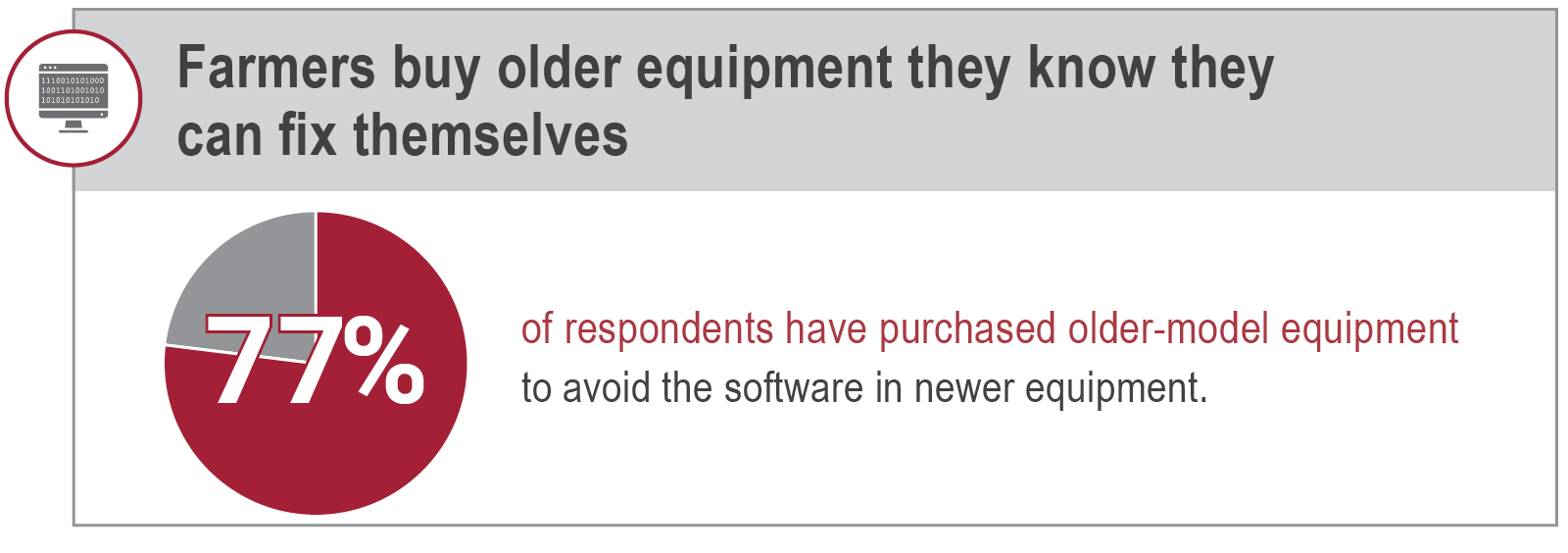

The dealership landscape can also affect which equipment farmers purchase. Some farmers forgo modern equipment altogether; 77% of the 74 farmers U.S. PIRG Education Fund and National Farmers Union surveyed have purchased older-model equipment to avoid the software in newer equipment that requires dealership fixes.

Buy whatever is the closest dealership to you because those are the people that you need to help fix your stuff. When you need a part, the distance of that drive to the dealership means a lot.Wyatt Parks

Minnesota farmer

But not all farmers want to rely on decades-old tractors. When people ask Wyatt Parks, a Minnesota farmer, which tractor to buy, he tells them to, “buy whatever is the closest dealership to you because those are the people that you need to help fix your stuff. When you need a part, the distance of that drive to the dealership means a lot.”

When farmers don’t trust or don’t like their closest dealership, consolidation can require them to drive hundreds of miles to get a second opinion from another chain. That presents a dilemma for farmers: Deal with the poor service or high prices that their closest dealership offers, or spend hours transporting your equipment to a competitor?

Even if [manufacturers] had this repair monopoly, if they had some segmentation, it would provide some incentive for these dealerships to do a better job. And the fact that they have consolidated so much means that they absolutely don’t have to at all, because you just have no other choice.Jared Wilson

Missouri farmer

“I want to emphasize just how much consolidation is affecting this,” Missouri farmer Jared Wilson told U.S. PIRG Education Fund. “Even if they had this repair monopoly, if they had some segmentation, it would provide some incentive for these dealerships to do a better job. And the fact that they have consolidated so much means that they absolutely don’t have to at all, because you just have no other choice. It’s not practical to take your 20 ton machine and move it 300 miles to go get work done. The logistics of that just don’t work.”

Agricultural Right to Repair reforms would go a long way to solve these problems, unlocking existing repair infrastructure and allowing for further expansion. Just as Right to Repair would allow a farmer to fix their own equipment, it would also enable a Kubota-branded dealership to service John Deere equipment or a Case IH mechanic to repair an AGCO combine. Independent mechanics would have access to repair information across all brands, meaning they could fix tractors regardless of the name on the hood.

Such policies are popular among the 74 farmers surveyed: 95% support Right to Repair. The current system, however, prevents much overlap, eliminating farmer choice.

By implementing Right to Repair reforms, state and federal lawmakers could unlock existing repair infrastructure to provide farmers with far more repair choices. They could precipitate the expansion of the repair market, creating opportunities for new independent repair businesses to open and supporting local jobs. State and federal lawmakers should implement Right to Repair to increase competition, improve customer service and lower repair costs for farmers.

Report ●

Report ●