A Perfect Storm

When tropical storms meet toxic waste

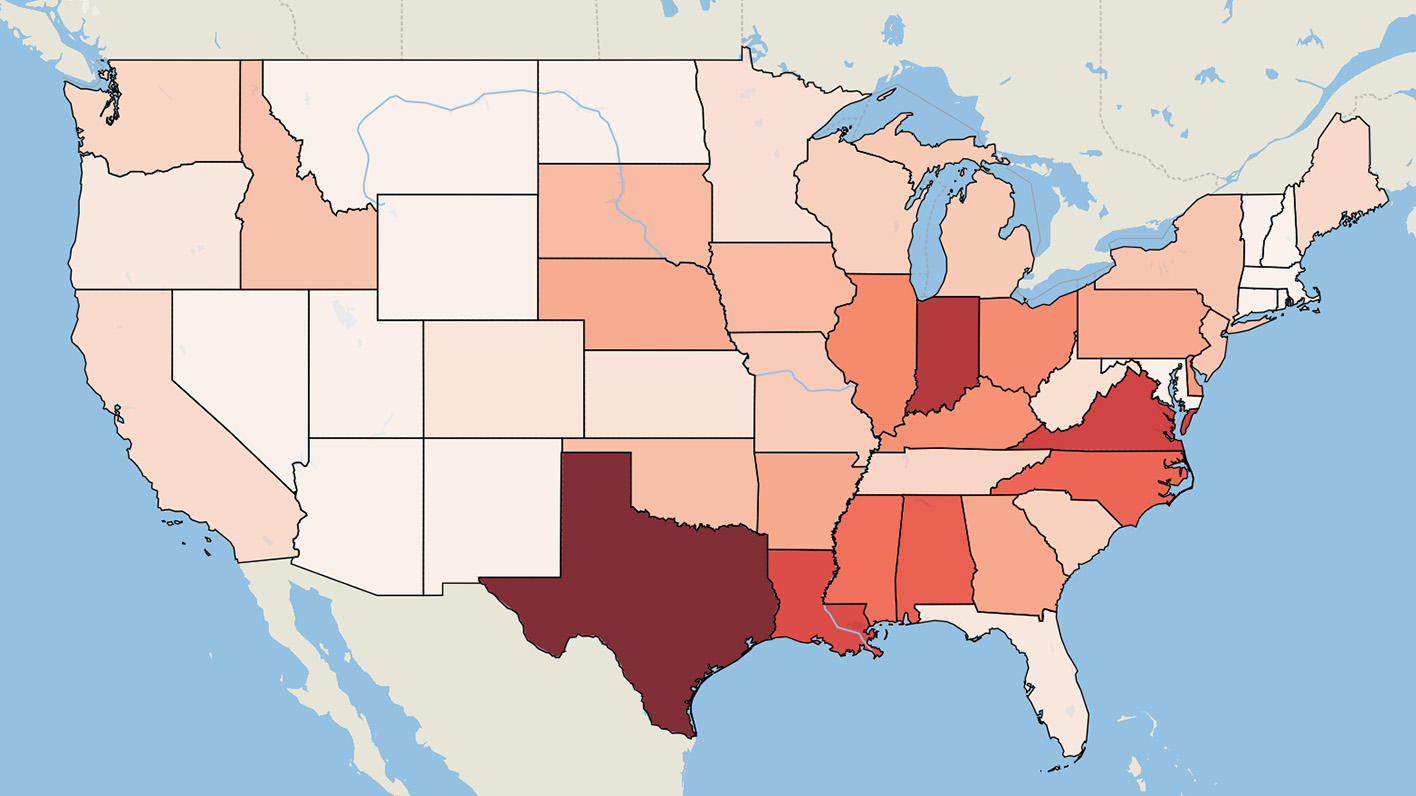

Today, one in five Americans lives within just three miles of a Superfund toxic waste site. Contaminants of concern at these sites include arsenic, lead, mercury, benzene, dioxin, and other hazardous chemicals that may increase the risk of cancer, reproductive problems, birth defects, and other serious illnesses. Cleanup can take a decade or more, and decreased funding over the last 20 years has led to slower cleanups. To make matters worse, climate change is increasing the frequency and severity of storms such as hurricanes that threaten to impact toxic waste sites, which could spread the chemicals at these sites into surrounding communities. During the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season, 810 Superfund toxic waste sites were in the path of a hurricane or tropical storm.

Downloads

U.S. PIRG Education Fund and Environment America Research and Policy Center

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

SINCE 1980, THE ENVIRONMENTAL Protection Agency’s (EPA) “Superfund” toxic waste cleanup program has been responsible for identifying the worst toxic waste sites across the country and holding polluters accountable to cover the cost of cleaning them up. When the polluting party cannot be found or afford the cleanup, the Superfund program has the authority and funds to clean up the site.

Contaminants of concern at toxic waste sites on the National Priorities List include arsenic, lead, mercury, benzene, dioxin, and other hazardous chemicals that may increase the risk of cancer, reproductive problems, birth defects, and other serious illnesses. Recent research also shows that living near one of these sites can lower life expectancy. Today, one in five Americans lives within just three miles of a Superfund site. Cleanup can take a decade or more, and decreased funding over the last 20 years has led to slower cleanups.

Meanwhile, each year natural disasters threaten to impact toxic waste sites.

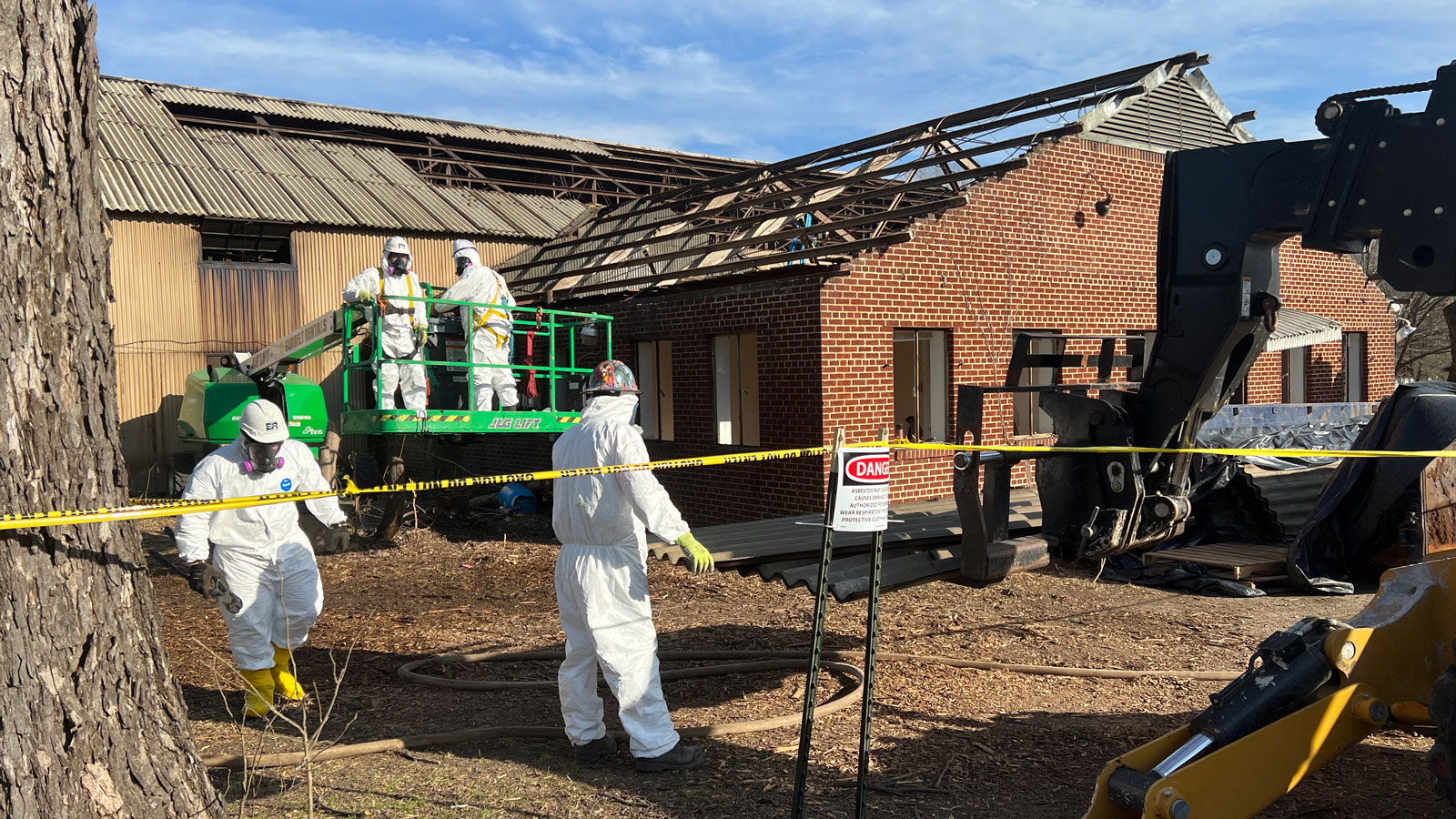

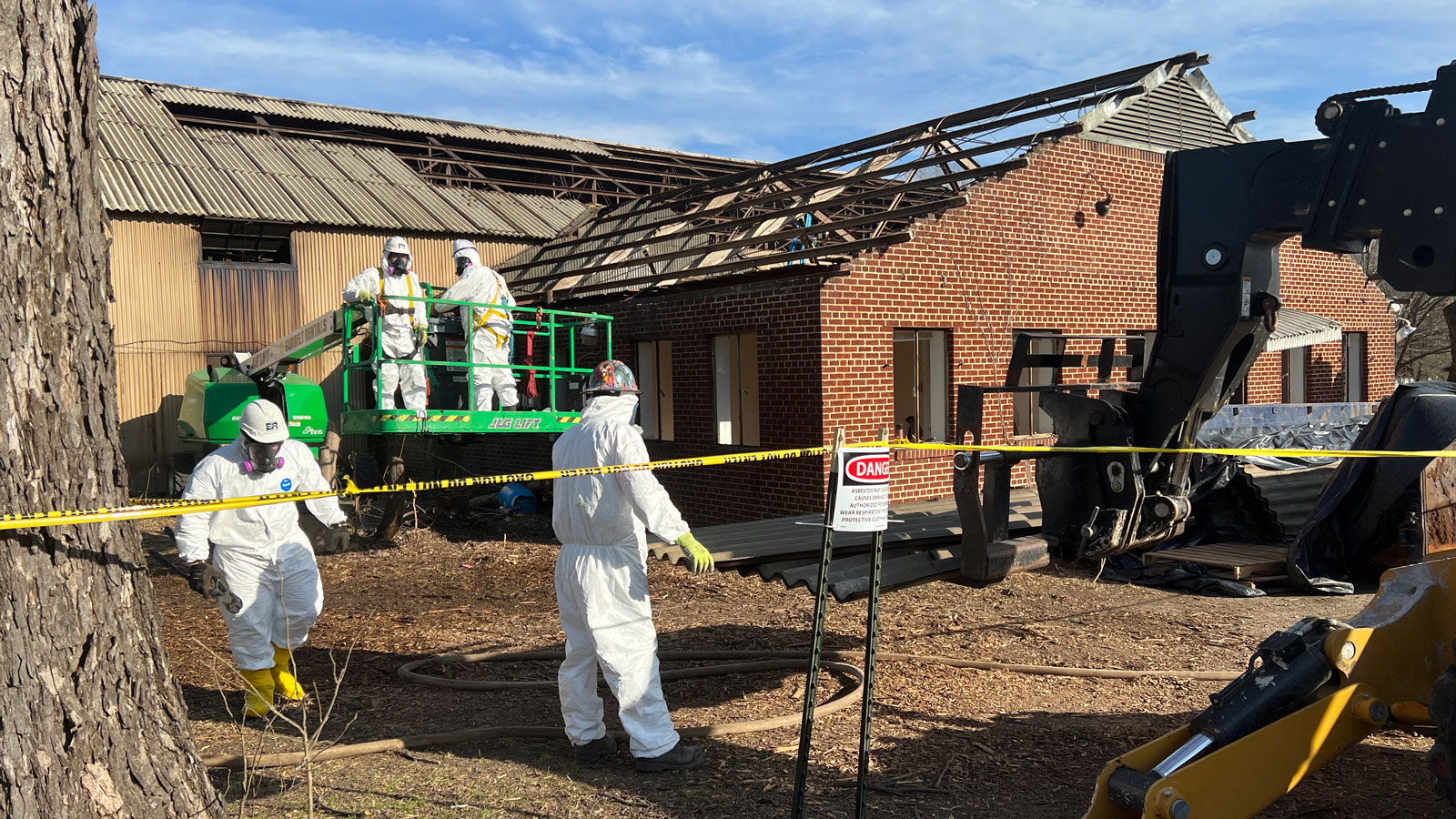

Tropical storms and hurricanes wreak havoc on impacted communities — from dangerous and costly wind and flood damage, to knocking out power for entire communities, to contaminating drinking water, to wiping out homes and destroying essential community resources. And some of these storms cause especially hazardous damage. Hurricane Floyd (1999), Hurricane Katrina (2005), Hurricane Irene (2011), Hurricane Sandy (2012), and Hurricane Harvey (2017) have all caused flooding at Superfund sites. With so much devastation upending people’s lives, the last thing anyone should have to worry about is the threat of toxic waste contaminating their water, soil, and air after a storm.

To make matters worse, climate change has caused the number of tropical cyclones with higher intensities to increase, including those responsible for the “great majority of [tropical cyclone]-related damage and mortality.”

In coming years, we can expect to see stronger storms more frequently, with the strongest storms becoming even stronger. Warm ocean water and air is fuel for tropical storms, which makes global warming a driving force in the more intense hurricanes we’ve been experiencing. Like rocket fuel in a race car, hurricanes are being supercharged by these warmer temperatures, causing more destructive storms.

Sea level rise has also made worse the most dangerous aspect of hurricanes: storm surge. Storm surge is the rise in tide above the normal level due to a storm, usually due to powerful winds pushing large amounts of water forward. Sea level rise from melting glaciers and ice sheets results in storm surge that reaches further inland, increasing the area and scale of the damage.

In addition, increased temperatures have allowed for more moisture to collect in the air, which becomes rainfall during a storm and can cause deadly inland flooding.

Last year’s Atlantic hurricane season broke several records for the number and severity of storms, highlighting the urgent need to clean up toxic waste sites as quickly and effectively as possible.

The 2020 Atlantic hurricane season broke the records for the most named storms (tropical cyclones with maximum sustained wind speeds greater than 39 miles per hour are classified as tropical storms and given a name). Prior to the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season, the average number of named storms per year was 18, including 6 hurricanes. The 2020 Atlantic hurricane season had 30 named storms, 12 of which were hurricanes. The 2020 Atlantic hurricane season also had the most named storms to make landfall in the U.S., and the second-most hurricanes ever recorded in a single Atlantic hurricane season.

During the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season, 45% of all Superfund toxic waste sites on the National Priorities List (NPL) were in areas affected by tropical storms and hurricanes.

To protect our communities from toxic waste spreading during a hurricane, we need to clean up these sites as quickly and effectively as possible. And clean-up plans and efforts need to take into account the risk of climate change related natural disasters to the security of toxic chemicals present at these sites to prevent their spread in the event of an impact.

Fortunately, only one NPL site was reported to be impacted during the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season. During Hurricane Isaias, the Clearview Landfill partially flooded, and areas in which cleanup was ongoing experienced erosion and required repairs.

The Clearview Landfill is on the east side of Darby Creek in Pennsylvania. It is one of two separate landfills that make up the Lower Darby Creek Area (LDCA) Superfund site. Much of the community near the landfill is in a 100-year floodplain, which means the area has a 1-in-100 chance of flooding in any given year, and are considered high risk areas by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Worse, depending on recent rainfall and storm surge events, a 10-year or 50-year storm event could cause the creek to flood the surrounding neighborhood.

During Hurricane Isaias, the Clearview Landfill partially flooded, and areas in which cleanup was ongoing experienced erosion and required repairs. Prior to the flooding, the EPA had removed and replaced contaminated soil at nearly 200 residential properties, which the EPA believes lowered the risk that floodwaters in the neighborhood would become highly contaminated. The areas of Clearview Landfill in which cleanup was complete did not breach during the storm.

The damage to the Clearview Landfill Superfund site at areas where cleanup was ongoing highlights the importance of cleaning up Superfund sites as quickly as possible, because areas that haven’t been remediated are more vulnerable to being damaged and spreading contamination during a storm.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) can take steps to reduce the risk of toxic waste spreading from a Superfund site due to climate-induced natural disasters and sea level rise.

While the Superfund program has in various ways addressed the threat to sites from climate change, according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), the EPA has yet to clarify how efforts to manage risks from climate change at Superfund sites align with the EPA’s agency-wide objectives. For example, the EPA’s 2018-2022 strategic plan includes no mention of the threat posed by climate change, which includes the risks to Superfund sites or any related infrastructure projects.

Failing to include the risk of climate change as an agency-wide priority undermines the ability of those conducting cleanup under the EPA to manage risks from climate change to sites undergoing cleanup or being proposed for cleanup. Those executing clean-up efforts cannot be certain that higher level officers at the EPA will support initiatives that would protect Superfund sites from the adverse effects of climate change.

Congress can also take action to expedite the cleanup of toxic waste sites to reduce the risk of contaminating communities in the event of severe weather.

Recently, multiple bills have been introduced that would reinstate what are often referred to as “Polluter Pays” taxes to fund the Superfund program. These taxes would generate the funding necessary to implement comprehensive long-term clean-up plans at Superfund toxic waste sites, speed up the clean-up process at hundreds of sites currently undergoing construction, and identify sites that should be added to the National Priorities List for cleanup. Further, these bills would alleviate the financial burden currently resting on taxpayers and shift it to the industries that create and profit off the products that contaminate Superfund sites.

Topics

Find Out More

The Threat of “Forever Chemicals”

Who are the top toxic water polluters in your state?