CFPB receives over 2,500 junk fee comments

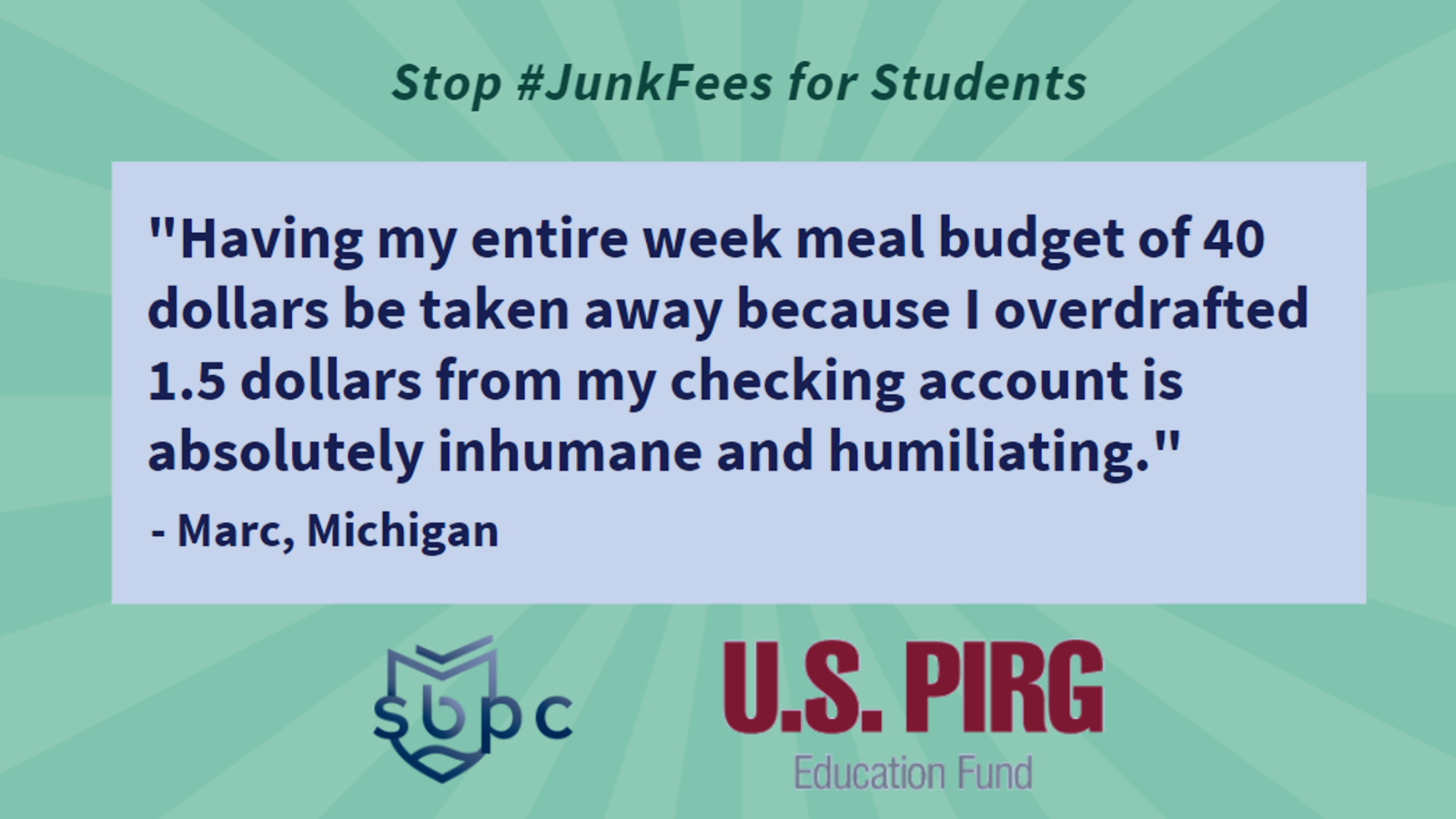

In response to a tidal wave of unfair marketplace practices, the CFPB asked the public to submit comments on the impact of junk fees on their lives. Some 2,500 comments later, consumers have described the pain points caused by unfair junk fees. Cover graphic courtesy Student Borrower Protection Center, used by permission

In response to a tidal wave of unfair marketplace practices, the CFPB asked the public to submit comments on the impact of junk fees on their lives. Some 2,500 comments later, consumers have described the pain points caused by unfair junk fees. Now the CFPB needs to act.

You can browse all 2,500+ comments filed at regulations.gov. For example, put the word “overdraft” in the search window on that linked page, you’ll find at least 920 entries to read. Try other words or phrases.

U.S. PIRG Education Fund filed two detailed comments. First, we joined the Student Borrower Protection Center to file a detailed comment on the devastating financial effects that junk fees have on students and other people who use credit and debt to finance postsecondary education. The comment draws on both our organizations’ work on campus credit and debit card fees and other junk fees associated with campus relationships with banks and other financial firms, including marketing agreements that a 2019 U.S. PIRG report had found, according to the comment, “were associated with students paying 2.3 times more in fees than students at schools without these marketing agreements. The Bureau has previously noted that paid marketing agreements between schools and financial institutions are often opaque and may cut against students’ interests.”

The joint comment with SBPC also drew from comments filed to the CFPB from students and past students:

“Current and past students commenting on the Bureau’s RFI reported forgoing groceries for weeks at a time, struggling to afford medicine (“God forbid I don’t calculate how much food and necessities like toilet paper and medication cost down to the last penny. If I make even a $1 or less error on costs, then I’m in the hole for $35 until my next paycheck, which means even less for necessities.”), eschewing electricity, rationing “toothpaste and toilet paper,”passing on the purchase of textbooks and other school supplies, grappling with eviction, facing deep personal humiliation, and more due to the cascading effects of junk fees from bank accounts. These junk fees include overdraft charges borne in moments of crisis or confusion, account maintenance fees prompted by declining balances, ATM fees that borrowers shoulder to access their own money, processing fees that leave students feeling that they are “being chipped away at,” account dormancy fees that penalize borrowers for not moving money frequently enough, and more.”

The comment includes detailed excerpts from each problem a student commenter identified above.

The second comment filed by U.S. PIRG Education Fund outlined the rise of junk fees on consumer credit card and bank accounts. From its introduction:

“In a series of bank and credit card reports, beginning in 1991, U.S. PIRG and U.S. PIRG Education Fund had studied the growth of unfair practices…Key findings of our reports:

— Big banks charge bigger fees.

— Banks have devised a three part strategy to gouge consumers.

(1) Increasing existing fees: PIRG’s 1995 Bank Fee Survey found that, from 1993-1995, bank fees on consumer accounts increased at twice the rate of inflation.

(2) Inventing new fees: Human teller fees and deposit-item-returned fees (charged consumers or businesses who deposit someone else’s bounced checks) are examples of other new fees, and,

(3) Making it harder for consumers to avoid fees: Includes, for example, changing “average” balance requirements on checking accounts to minimum balance requirements, as well as raising those minimums dramatically.”

The comment went on to explain how overdraft fees went from a deterrent to negative behavior, like a speeding ticket, to an enormous profit center as banks actually encouraged you to overdraft. Overdraft fees became “standard overdraft protection fees.” This meant small point-of-sale debits led to large overdraft fees. The $38 cup of coffee, with no exotic blends, was brewed: $3 for the coffee, $35 for the overdraft protection fee. We commented that the pre-CFPB regulators’ supposed solution — to require an opt-in for the “protection” product — has failed to protect consumers and called for CFPB action.

The comment then moved over to credit cards: We first explained how credit card companies, already the most profitable form of consumer lending, were tasked by Wall Street CEOs to extract greater revenue from consumers every year by using tricks and traps:

“Credit card banks began changing bill due dates, shortening the period between when bills were mailed and when bills were due, saying that payments that arrived after 11am on the due date were late, making bills due on a Sunday and declaring payments that arrived on Monday late. But more late payment fees from more consumers weren’t enough. Not enough profit, said the CEOs! Their next scheme was not only to charge a late payment fee but also ratchet up your interest rate to as much as 36% APR, retroactively on existing balances. Still not enough profit, said the CEOs! The banks then imposed universal default, saying consumers who’d always paid on time but were late to any other creditor were in default and that their APRs must go up. Still not enough profit, said the CEOs! So, the banks imposed “we can change the rules at any time, including for no reason” clauses and raised everyone’s rates!”

That section includes a link to my video remarks at a CFPB field hearing in 2013. Advance the event to time marker 36:08 for a 3-minute explainer as to the success of the 2009 Credit CARD Act in curbing many excesses of an out-of-control market.

But more needs to be done. While Congress did an incredible job in reining in unfair credit card tricks and traps in implementing the Credit CARD Act, the Federal Reserve then dropped the ball; it approved high credit card late fees with an escalator clause.

Glad the Fed’s no longer in charge! Now, the CFPB needs to act. In 2022, credit card banks can charge a $30 late fee for a first offense and $41 for subsequent offenses within six months.

Of course, the banks aren’t the only ones peddling junk fees on unsuspecting consumers. Our comment included the following coda:

“While we have concerns about a variety of junk fees in the broader consumer marketplace, including so-called DRIP fees, which are surprise or ancillary fees revealed only after purchase of concert tickets, hotel reservations, rental cars and airline tickets, we limit this comment to common bank and credit card fees that cause pain points for consumers. A vast number of other junk fees likely come under the CFPB’s jurisdiction and we encourage the CFPB to act when they do and to inform other agencies when appropriate.”

If we hadn’t stopped with student junk fees and common bank and credit card junk fees, we’d still be writing the comment! Thanks to the CFPB for it’s leadership here; now, it’s time for the CFPB to act further to tame financial markets. Kudos to CFPB director Rohit Chopra, who has used his bully pulpit to warn banks about junk fees from credit card late fees to overdraft fees. He’s already cajoled some banks into limiting their use of unfair overdraft fees; it’s a start. He knows, and we know, that the banks and other actors have taken their teeny steps so far solely to avoid further limits on their tricks and traps. Further limits are still needed. We can’t wait!

Topics

Authors

Ed Mierzwinski

Senior Director, Federal Consumer Program, U.S. PIRG Education Fund

Ed oversees U.S. PIRG’s federal consumer program, helping to lead national efforts to improve consumer credit reporting laws, identity theft protections, product safety regulations and more. Ed is co-founder and continuing leader of the coalition, Americans For Financial Reform, which fought for the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010, including as its centerpiece the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. He was awarded the Consumer Federation of America's Esther Peterson Consumer Service Award in 2006, Privacy International's Brandeis Award in 2003, and numerous annual "Top Lobbyist" awards from The Hill and other outlets. Ed lives in Virginia, and on weekends he enjoys biking with friends on the many local bicycle trails.

Find Out More

Apple AirPods are designed to die: Here’s what you should know

A look back at what our unique network accomplished in 2023

Avoiding scams, incorrect medical bills, privacy invasions and more