‘Chromebook Churn’ report highlights problems of short-lived laptops in schools

Chromebooks are not designed to last. Google could double the life of these widely used laptops, saving schools money and helping the environment.

The pandemic pushed schools to provide every student with their own device, often turning to Chromebooks. A laptop for every student is likely here to stay, but now this new tech is failing. That’s because while we know milk goes bad, it turns out Chromebooks have expiration dates too.

Downloads

None of us can afford to stay on the disposability treadmill. All tech should last longer, and Google can lead the way by fixing the Chromebook Churn.

Beginning of the Chromebook Churn

Especially since the start of the pandemic and the widespread implementation of remote learning, school districts have looked for a budget laptop that they can buy en masse and then distribute to students. For many, Chromebooks seemed like the answer. In the last quarter of 2020 Chromebooks sales were 287% higher than in 2019.

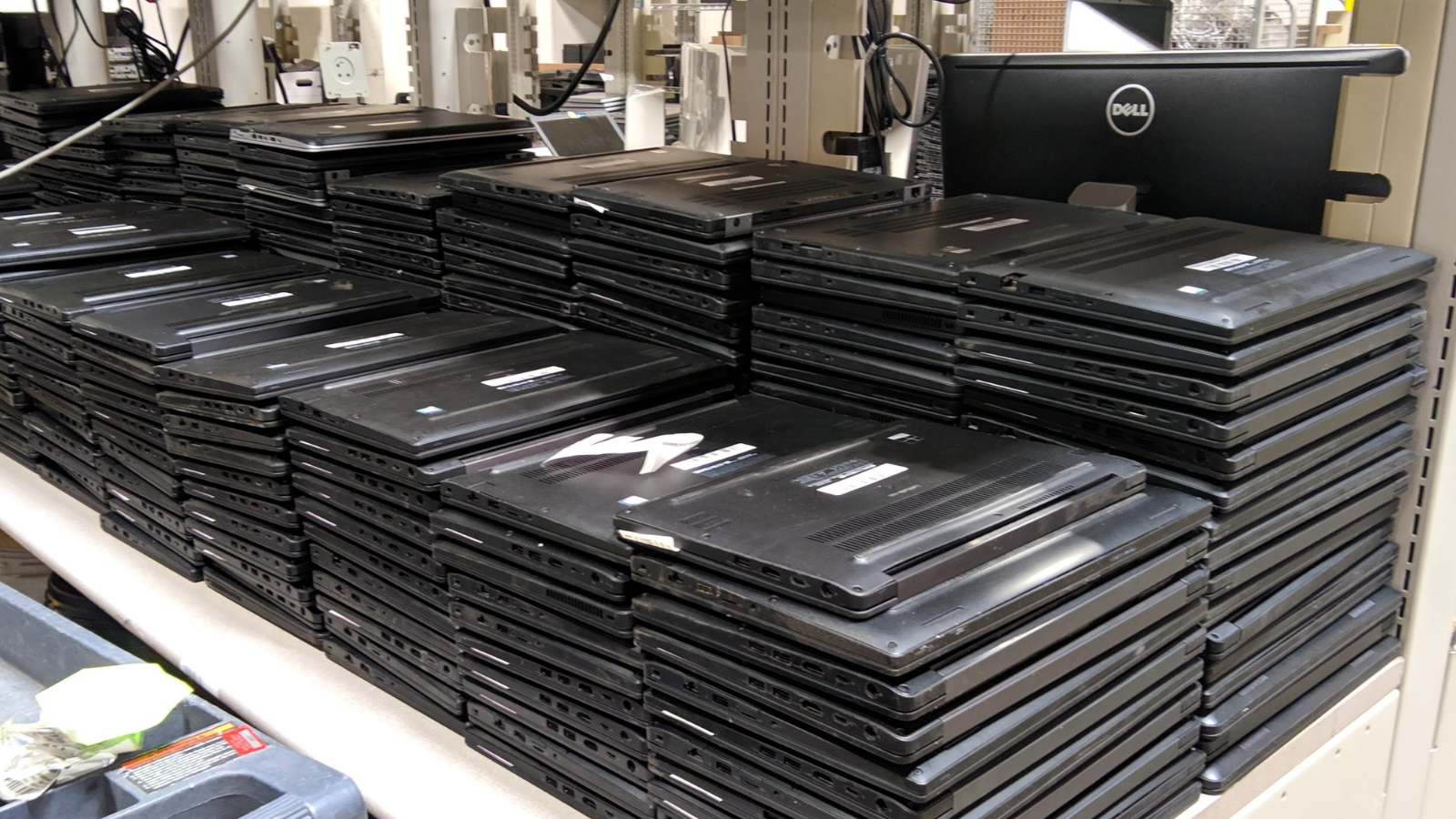

Now three years later, schools are beginning to see their laptops fail, creating piles of electronic waste and saddling schools with additional costs.

Schools have piles of working Chromebooks that have become e-waste because they’ve expired.

Why this matters

How the Chromebook Churn affects schools

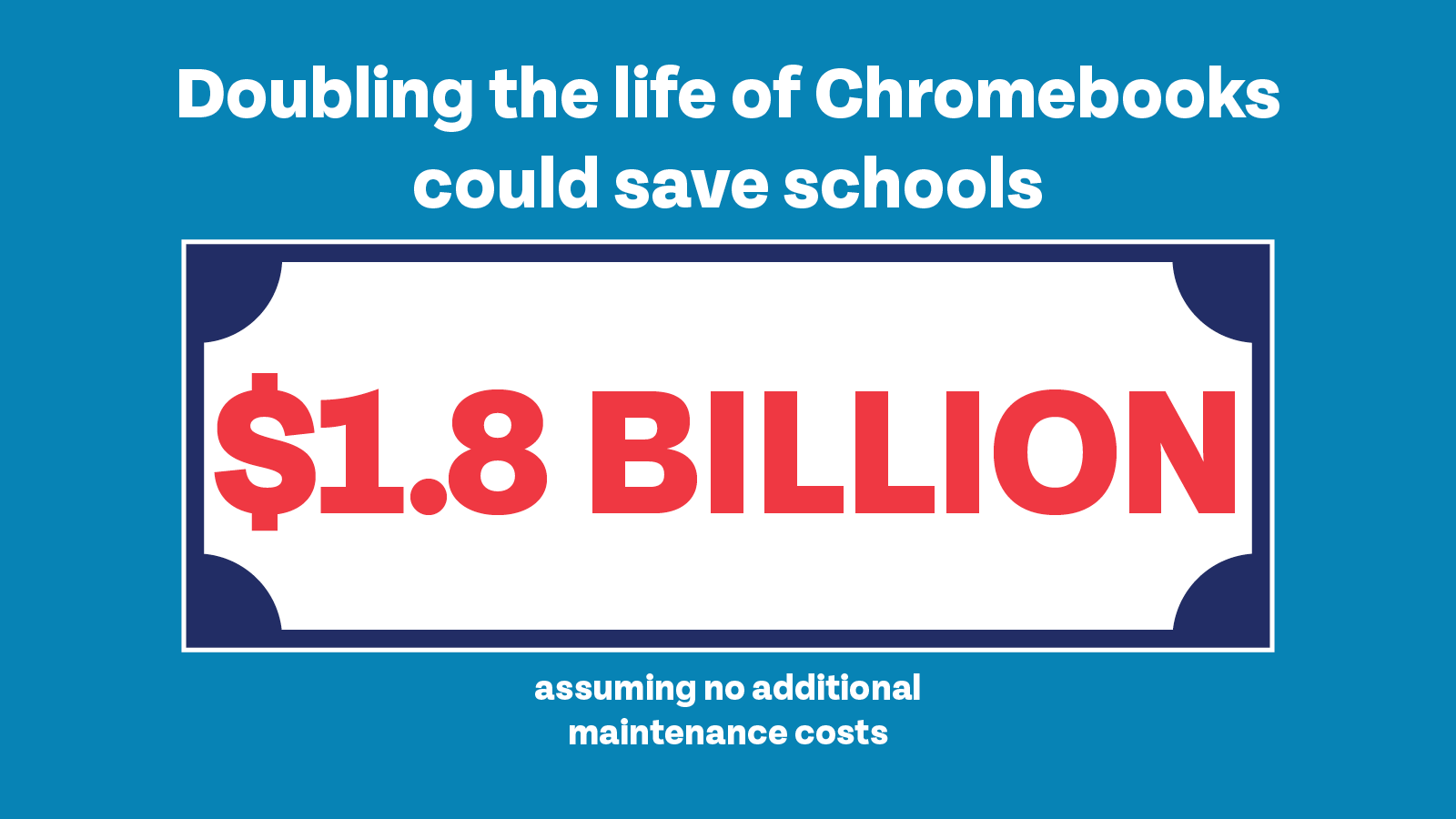

According to a March 2021 Education Week survey of school leaders, 90 percent of middle and high schools and 84 percent of elementary schools were providing a device for every student. One-to-one policies where every student gets a laptop are likely here to stay. Which means the consequences of balancing utility and sustainability are huge. Interviews with school IT staff reveal Chromebooks typically last four years. Across the 48.1 million K-12 public school students in the U.S., doubling the lifespan of Chromebooks could result in $1.8 billion dollars in savings for taxpayers, assuming no additional maintenance costs.

See how the Chromebook churn affects your state

Chromebooks take a heavy toll on the environment

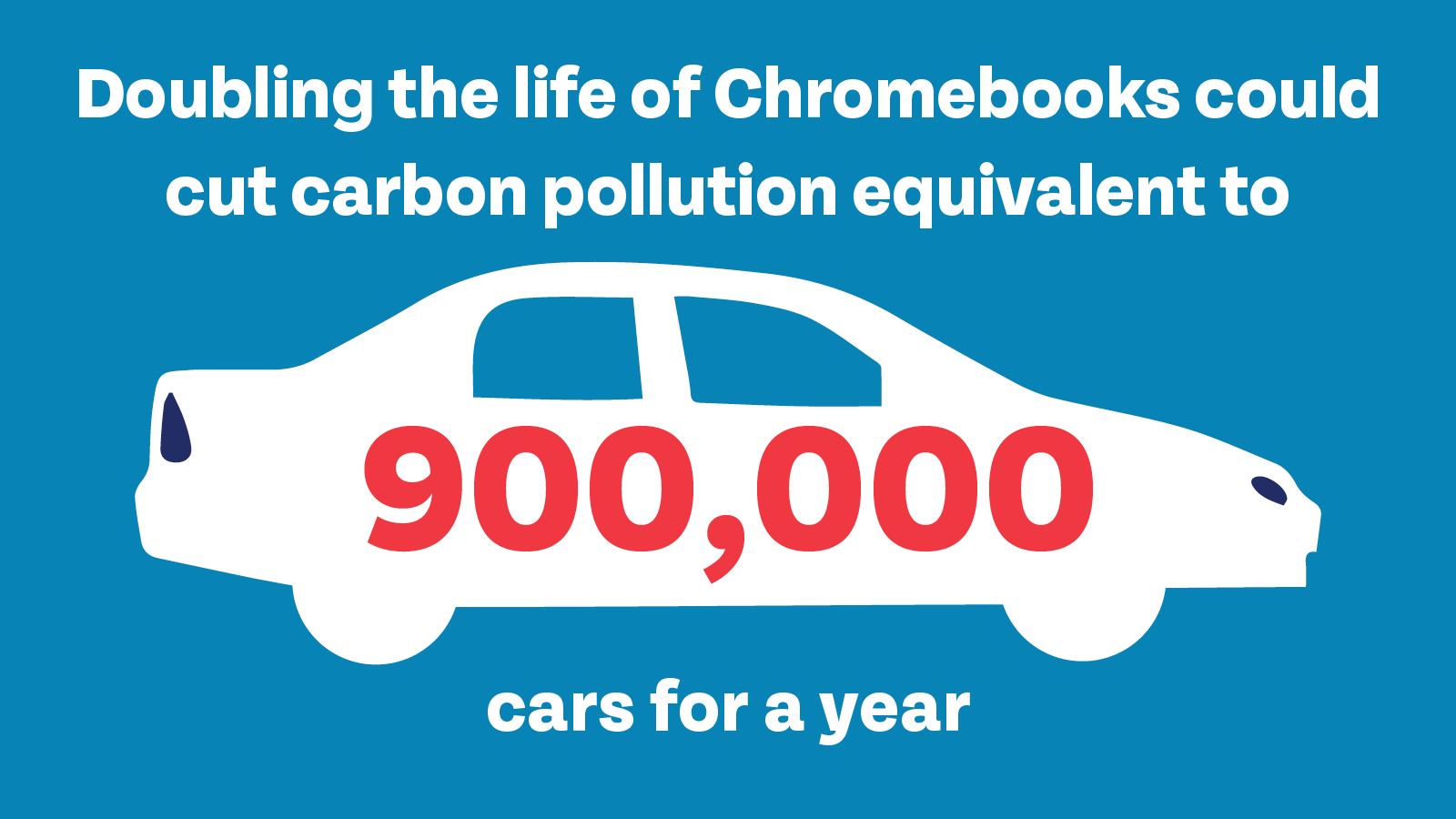

Manufacturing a computer consumes a great deal of resources. In fact, some estimate that the information technology sector is responsible for about as much greenhouse gas emissions as the airline industry. The over 31 million Chromebooks sold globally in the first year of the pandemic represent approximately 8.9 million tons of CO2e emissions.

We can’t recycle our way out of the problem. When technology like Chromebooks reach their expiration date, only one-third of this electronic waste is properly recycled. If it isn’t designed to last, our environment pays the price.

Why Chromebooks fail

1. Chromebooks have a built-in “death date,” after which software support ends.

We expect milk to expire, but not laptops. Adding to customer confusion, expiration dates are based on the certification of a given model, not the purchase date. This means that consumers or schools can buy a used or refurbished Chromebook thinking they’re getting a great deal, only to be surprised when their new laptop expires after a year.

“To get future updates, upgrade to a newer model.”Photo by Peter Mui | Used by permission

Once laptops have expired they don’t receive updates and can’t access secure websites. For example, instructors have reported that expired laptops can’t access online state testing websites.

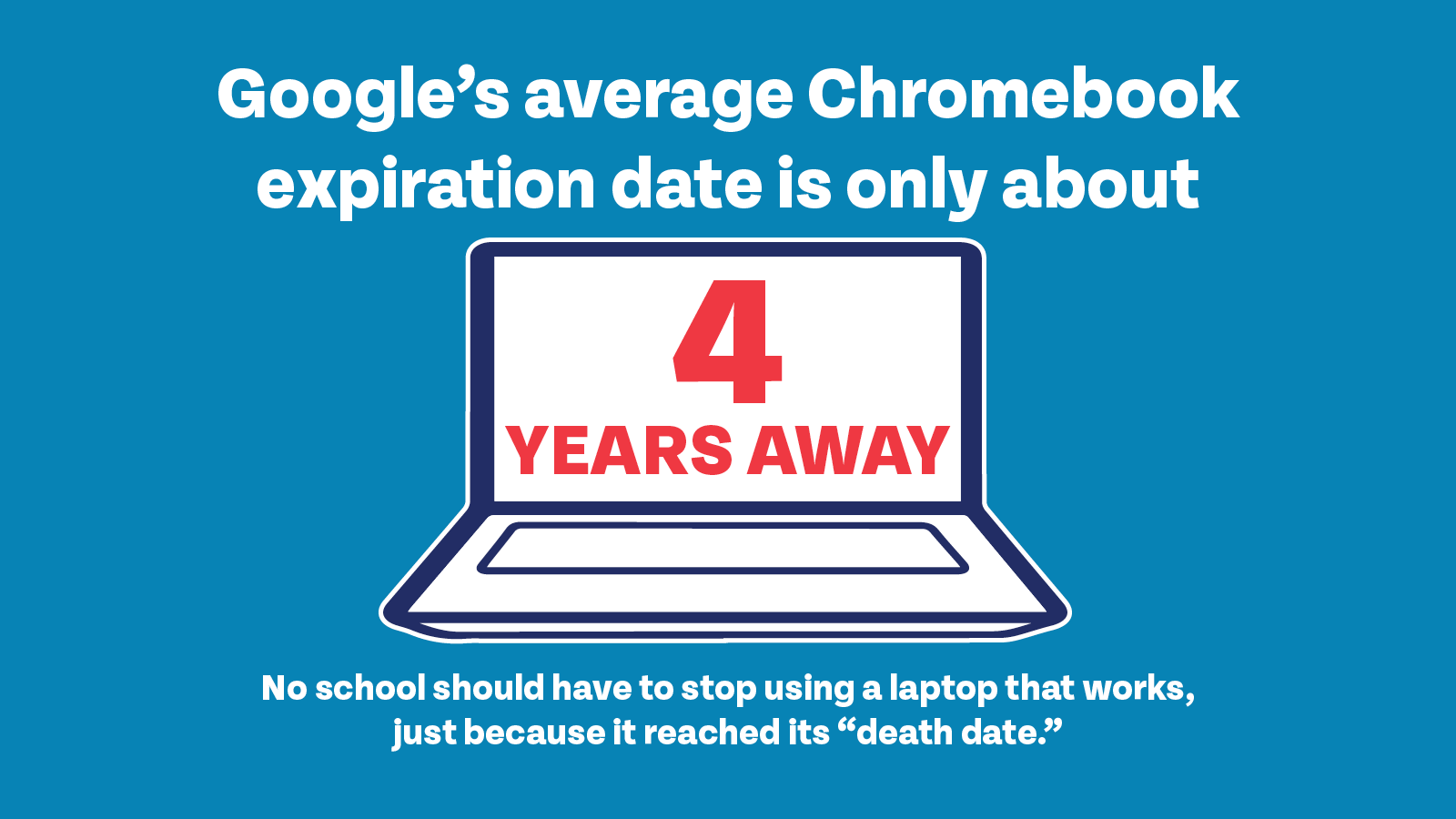

As of this report’s release, Google’s lists the average expiration date for all devices as four years away. While Google has taken steps to increase expiration dates, these changes still fall short of what is needed to reduce e-waste.

No school should have to stop using a laptop that still works, just because it’s reached its “death date.”

2. Manufacturers who make Chromebooks typically do not sell new spare parts or otherwise support repair.

It’s challenging to find spare parts to repair Chromebooks. The lack of spare parts produced by manufacturers makes them hard to source and expensive. Currently, schools need to purchase parts from third-parties or scavenge from broken machines. This scarcity can contribute to the high price for parts, making repair uneconomical. For example, 10 of the 29 keyboards we reviewed cost $89.99 or more, which is nearly half the cost of a typical $200 Chromebook.

As part of our previous report, “Failing the Fix,” we evaluated the detailed repairability information required from manufacturers in France. There were 11 Chromebooks currently for sale where we could find this repairability information, which the French turn into a “Repair Score” on a 0-10 scale, like an EnergyStar label for repair. The 11 Chromebooks we reviewed had an average parts availability rating of 3.3 out of 20, much lower than the average non-Chromebook laptop, which averaged out to 9 out of 20.

3. The way these laptops are designed frustrate repair and reuse.

To reduce e-waste, the parts for these laptops should be highly compatible, allowing commonly used parts to be shared across a range of models. Parts that wear down over time or frequently break—such as the battery, screen and keyboard—could be taken from older or broken devices and used to fix newer devices. However, school technicians point out that updates to popular models often include arbitrary changes that frustrate repair and use.

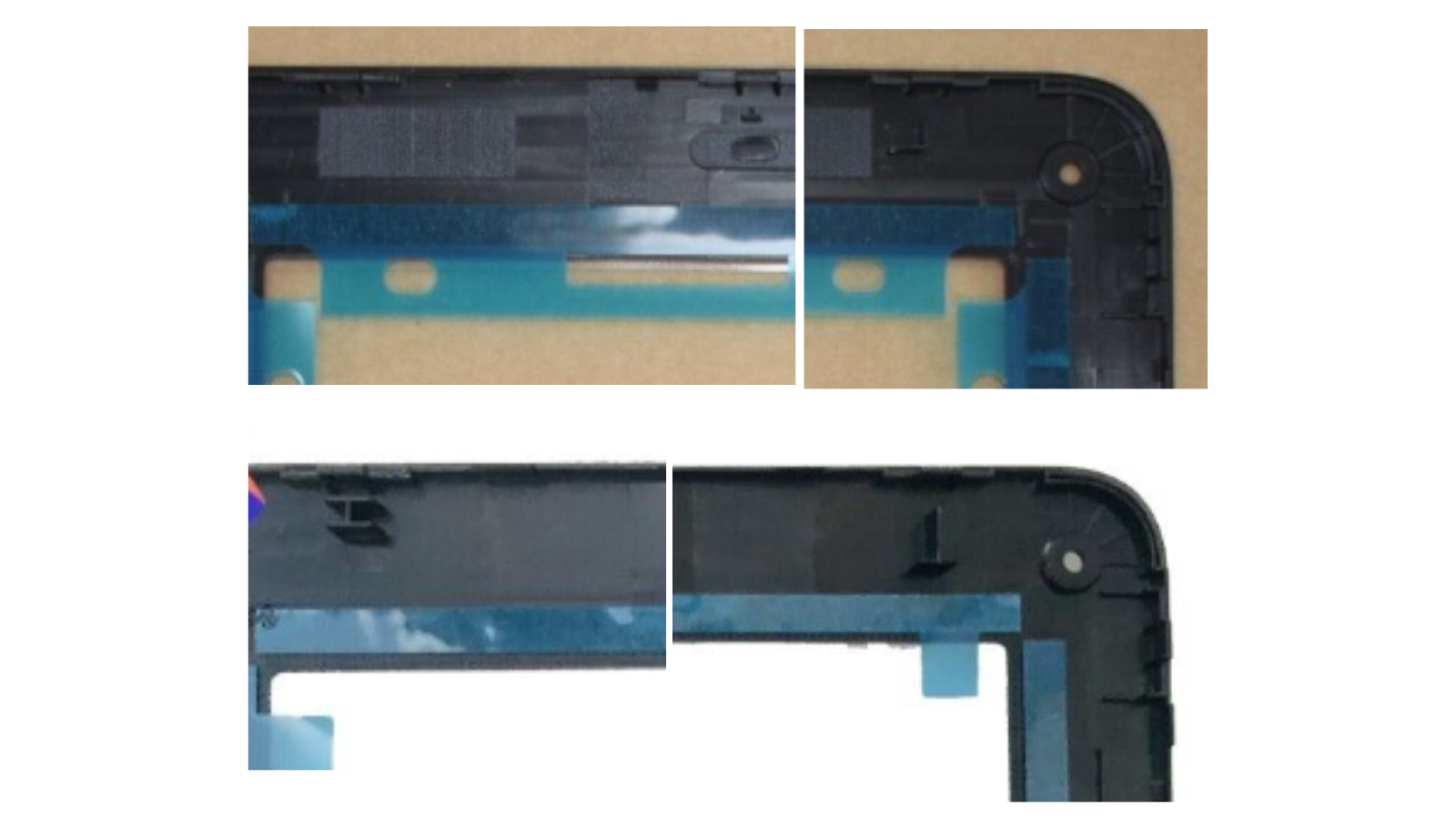

Most Chromebook have a piece of plastic that goes around the edge of its screen called a “bezel.” Our report found all six of the manufacturers on edu-parts.com, a popular parts reseller, made non-functional changes to the plastic bezels of their Chromebook 11 models that made these parts incompatible from one model to the next.

For example, from the Dell 11 Chromebook 3100 and 3110 bezels, the only visible changes are the addition of small notches on the bottom of the newer model. On the back of the bezels we can see that 3110 has missing or less pronounced clips which renders them incompatible.

Can you spot the difference?

Left to right: the Dell 11 3100 Non-touch Chromebook Bezel and Dell 11 3110 Non-Touch Chromebook Bezel. These parts are not compatible across models

Photo by Edu-Parts | Used by permission

Top to bottom: 3100 and 3110 bezels. The only external changes between these parts are the addition of small notches on the bottom of the newer model.

Photo by Edu-Parts | Used by permission

Top to bottom: Close-up images of the upper right back edges of the 3100 and 3110 bezels. The 3110 has missing or less pronounced clips which renders these parts incompatible.

Photo by Edu-Parts | Used by permission

1of 3

How Google can lead the industry on sustainability

If we’re going to give every student a laptop, they should be designed to last. Google could significantly increase the lifespan of all Chromebooks being used by extending their Automatic Update Expiration (AUE) date. Our tech should last longer, and Google can lead the industry.

Extend the life of Chrome OS software: Too many working Chromebooks end up as e-waste due to the end of software updates. Google should extend all model’s Automatic Update Expiration (AUE) to 10 years after its launch date.

Extend the life of the Chromebooks hardware: Chromebooks aren’t designed to last, but Google has the power to change that. Google can work with Chromebook manufacturers, pushing them to produce spare parts, and standardize part design to the greatest extent possible. This would reduce electronic waste and increase repairability.

We have a stuff problem

We have a massive stuff problem. We don’t need most of it and too much of it is built to be disposable. We shouldn’t allow planned obsolescence that keeps us buying more all the time. The least we can do, if we’re giving every student in the U.S. a laptop, is ensure these devices are durable and repairable—not part of a constant churn.

We can’t afford to produce disposable technology at this rate. Electronic waste is less than two percent of the world’s waste stream by volume, but causes over 70 percent of the waste stream’s harmful and toxic environmental effects.

We need Google and all manufacturers to make products that last and we should be teaching our children the importance of sustainability. With more tech in our lives and classrooms, if Google wants to be the source of hundreds of millions of laptops for our students, they need to do it right.

Topics

Authors

Lucas Gutterman

Director, Designed to Last Campaign, U.S. PIRG Education Fund

Lucas leads PIRG’s Designed to Last campaign, fighting against obsolescence and e-waste and winning concrete policy changes that extend electronic consumer product lifespans and hold manufacturers accountable for forcing upgrades or disposal.

Find Out More

‘Failing the Fix’ scorecard grades Apple, Samsung, Google, others on how fixable their devices are

Fixed for the Holidays

Green schools guide