Testimony before the House Public Utilities Committee in opposition to House Bill 1472

House Bill 1472, House Floor Amendment 1 is complex, sophisticated legislation, but can be summarized simply: it doubles down on the worst policies passed during ComEd’s corrupt scheme, and makes them even worse.

Chairperson Walsh, Vice Chairperson Delgado, Spokesperson Wheeler, honorable members of the committee: thank you for the opportunity to testify today. My name is Abraham Scarr and I am the Director of Illinois PIRG. Illinois PIRG is a statewide, citizen funded, non-partisan public interest advocacy organization that speaks out for a healthier, safer world in which we’re freer to pursue our own individual well-being and the common good.

Summary

House Bill 1472, House Floor Amendment 1 is complex, sophisticated legislation, but can be summarized simply: it doubles down on the worst policies passed during ComEd’s corrupt scheme, and makes them even worse.

This is best demonstrated by how the legislation handles ratemaking. While it claims to end formula rates and return to traditional ratemaking, the legislation in fact transitions to formula rates by another name. The fundamental architecture of formula rates, which guarantees utility profits but not customer and public benefits, remains.

The primary difference between formula rates as they exist now and as they would exist if this legislation becomes law is that the utilities’ profit level from grid spending would no longer be set by formula, but by regulators. However, regulators would be bound within a specific range based on profit rates across the country, profit rates from utilities whose profits are not guaranteed as ComEd and Ameren’s are. This change appears to give authority back to regulators, but is designed to increase the profit level enjoyed by ComEd and Ameren.

While packaged as addressing the climate crisis and layered with regulatory complexity, this legislation’s primary purpose is clear — to increase the profits of Exelon Corporation, directly and through its subsidiary, ComEd. Should it become law, the result will be a slower, more expensive transition to a clean energy economy, unduly controlled by private interests rather than democratically accountable institutions.

For perspective, ComEd’s authorized profits were roughly $465 million in 2014. If ComEd continues to enjoy the advantages of formula rates as it would under this legislation and applies a higher profit level included in this legislation, its annual authorized profits will be roughly $1 billion, if not more, by next year.

Is it the policy of Illinois that this more than $500 million increase in annual, guaranteed ComEd profits, an amount that more than doubled ComEd’s profits within a decade, is necessary for ComEd to meet its service obligations? Imagine what this level of annual investment could do if, instead of going to Exelon, was invested in building the clean energy generation required to move Illinois to 100 percent renewable energy.

This is but one example of how this legislation doubles down on the misguided policies passed while ComEd was engaged in its bribery scheme, unnecessarily prioritizing Exelon profits over the transition to clean energy. Below are more examples.

Instead of doubling down the policy legacy of ComEd’s bribery scheme by passing this legislation, or including these policies in negotiated omnibus energy legislation, the General Assembly should restore meaningful public oversight of utility operations and profits, and recenter utility policy on maximizing the public good.

Ratemaking

First, while this legislation claims to “transition back to a traditional rate case recovery process and tariff to replace its formula rate tariff,” it does so in a manner that maintains the key elements of formula rates.

Under formula rates, the annual formula rate update includes both a 1. forward looking process to determine the following year’s revenue requirement, and 2. a backwards looking process to reconcile the previous years revenue requirement with actual revenue and expenses.

This process is outlined in Sec. 16-108.5 (d)(1). A review of HB1472 HFA1 demonstrates that this process is preserved in the proposed legislation.

Sec. 16-108.5 (d)(1), the current formula rate, describes the forward looking process:

The inputs to the performance-based formula rate for the applicable rate year shall be based on final historical data reflected in the utility’s most recently filed annual FERC Form 1 plus projected plant additions and correspondingly updated depreciation reserve and expense for the calendar year in which the inputs are filed. (emphasis added)

The same basic language can be found in HB1472 HFA1 Sec. 9-201.1 (b)(1) in combination with subsection (c):

The modified test year period shall consist of final data for the most recent full historical calendar year, plus projected plant additions and correspondingly updated depreciation reserve and expense for the calendar year in which the general rate case and data are filed […]

(c) The data submitted by an electric utility in support of its general rate case filing shall be based on the utility’s applicable filed Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) Form 1, to the extent practicable and to the extent the utility’s test year period is based on a historical, calendar year test year. (emphasis added)

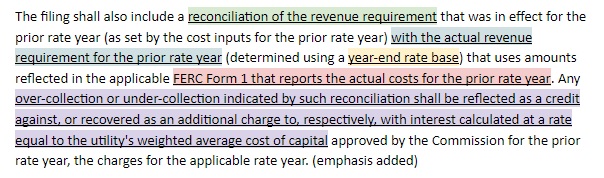

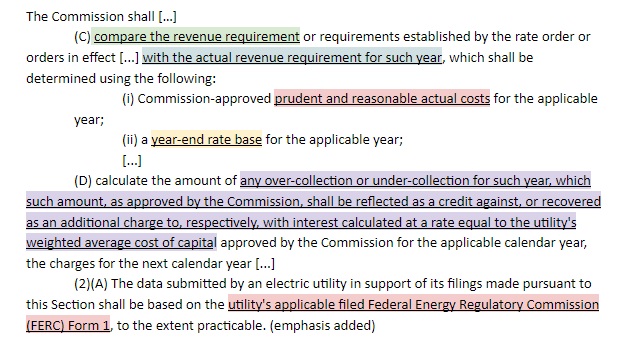

Sec. 16-108.5 (d)(1), the current formula rate, continues, describing the reconciliation process. To assist the reader I have color coded the relevant sections that are repeated in HB1472 HFA1.

In HB1472 HFA1, the reconciliation process, renamed the “Standards and compliance investigation,” maintains the same reconciliation process as the current formula rate law. The process is described in Sec. 9-201.2 (a)(1) in combination with subsection (2)(A)

Annual reconciliations based on actual costs allow ComEd to easily earn additional profits by spending more. To simplify for an example, let’s say ComEd was planning to spend $100 in a given year on grid investments expected to last ten years. ComEd would recover roughly $121 back over time. However, if ComEd ended up spending $200 that year, not only would it be able to automatically recover an additional $121, it would recover an additional $7 as interest on the under-collected amount for one year. The company is allowed to earn interest at this level despite only a short-term lag in collecting guaranteed revenue and profits.

Consider the incentives this reconciliation process gives the company. This legislation maintains these unfair advantages for ComEd and Ameren and is misleading in doing so.

Second, embedded in the above language are ComEd profit boosters not originally included in the 2011 Energy Infrastructure Modernization Act, but added in a 2013 trailer bill after ComEd did not win accounting outcomes it sought at the Illinois Commerce Commission.

These are reflected in the “year-end rate base”, and “weighted average cost of capital” referenced above as well as pension benefits referenced in the Beneficial Electrification formula rate section on page 306 line 17-23. That section also anticipates that such pension expenses could be recovered in a general rate case.

Third, the proposed rate making process increases ComEd’s profits.

In ICC Docket No. 20-0393, the utility’s last completed rate case, ComEd’s Return on Equity (ROE), or profit level, was 8.38 percent. This ROE was calculated by taking the 12 month average of the rates of 30-year Treasury Bills plus 580 basis points, or 5.8 percent. ComEd’s overall Weighted Average Cost of Capital, or Rate of Return, of 6.28 percent was used to calculate ComEd’s authorized profits at around $757 million for this year.

Under this legislation, ComEd will be earning rates set by the Commission which must be between the 30th percentile and the 70th percentile of the national average [1]. During a recent Senate committee hearing, Illinois Commerce Commission staff estimated the national average at 9.4 percent and Office of the Illinois Attorney General staff at 9.6 percent. The last time the Commission set ComEd’s ROE, it set it at 10.5 percent in 2010.

Were a 9.6 percent ROE used in ComEd’s last formula rate update, ComEd’s annual authorized profits would have been more than $100 million higher. Applying that increased profit level to all of ComEd’s spending subject to the margin this year would increase ComEd’s annual authorized profits to $1 billion next year.

Fourth, the ratemaking section includes a provision, 9-210.1 (e), which offers a way to “smooth out” a rate increase by phasing it in over two years rather than all at once. While appearing to be in the consumers’ interest, this provision would end up costing consumers more, as the portion of the rate increase “held back,” over the first year would be treated as a regulatory asset earning a “carrying cost” of roughly 7 percent. Spreading the recovery over years allows the company to add profits in the form of interest. Customers receive no added utility service benefit in exchange for paying more to increase ComEd’s profits in this manner.

Sections 9-201.2(b)(1)&(2) also include provisions that allow the company to approach “final accounting and retroactive rate adjustment,” a policy ComEd won over the course of its scheme, in multiple ways, allowing the company to use whichever way is most profitable. Overall, this legislation allows the company to initiate multiple and various types of Commission dockets in order to achieve its desired outcome, splitting up and deferring portions of costs for more interest, spreading out cost recovery for more interest, and going back to the Commission to revise tariffs already implemented in order to increase profit levels.

Beneficial electrification

Section 8-016 creates a new Beneficial Electrification Portfolio Standard. We fully support transitioning our transportation and building sectors to being powered by a 100 percent renewable electrical grid. Doing so, however, does not require creating a new profit center for ComEd, as this legislation does. The costs of the Beneficial Electrification Portfolio Standard could be recovered through a formula rate separate from the ComEd’s general tariff.

As noted directly above, this legislation allows multiple and various avenues for the ComEd to recover its revenue and profits under favorable conditions to the company. On top of that, the legislation specifically requires a new profit center, or “regulatory asset,” for ComEd outside of delivery rates. As illustrated by a recent article, due to another regulatory asset separated from ComEd’s delivery rates, ComEd customers will pay ComEd $34 million more for delivery service in 2021, while delivery rates alone declined by $14 million. Separating out profit centers allows ComEd more automatic profit increases and increases in what customers pay ComEd, while touting a misleading “rate decrease” to customers.

Public policy should create opportunities for public utilities to profit when deemed necessary to incentivize beneficial public outcomes. There is no reason to create this new profit center for ComEd, which will benefit significantly from beneficial electrification.

If Illinois utilities are unable or unwilling to deliver beneficial electrification outcomes without overly generous incentives, the General Assembly should consider requiring investments and tasking a third party, such as the Illinois Power Agency, to manage it. This has worked well for driving electrical supply costs down.

Illinois Commerce Commission oversight

The legislation further weakens the Illinois Commerce Commission’s oversight in various ways.

One example is by impossibly short timelines, such as in Sec. 8-218(f)&(g) which require the Commission to approve, or approve with modifications, a Clean Energy Integrated Distribution Plan in the time the Commission typically takes to rehear a case that has already established an entire record. The Commission has even less time to review plans for soliciting public input and for cost saving measures. If the Commission rejects a plan, it will have even less time to review the new plan submitted by the utility. The Commission has only 60 days to review annual reports on ComEd’s performance metrics. To pick a final example out of multiple remaining, the legislation allows ComEd to shorten the time of a rate case by a little over a quarter of the time it would properly take. These impossibly short timelines necessarily reduce scrutiny. This serves to further guarantee ComEd’s desired outcomes.

As another example, the legislation directs the Commission to hold public workshops to examine ComEd’s spending plans. The information provided by the company, however, is only intended to be a so-called “flexible planning tool.” The information provided by ComEd cannot be used in any formal proceeding to show what the company actually plans to do.

Nuclear subsidies

Illinois consumers have been overpaying for Exelon’s nuclear power plants since the 1980s. Cost pressures from construction overruns contributed to ComEd’s chronic underinvestment in its distribution infrastructure, leading to decades of poor reliability performance that has only recently been remedied, at further significant cost to consumers. This legislation puts Illinois consumers on the hook for even more subsidies to these plants.

Exelon’s aging, expensive power plants should not receive further direct public support unless such support is narrowly tailored and time-bound to meet a specific need as identified by outside certified accounting. Any such direct support should have guardrails and stronger provisions to end and claw back support if market conditions change making such narrowly tailored public support unnecessary. Any such direct support must only come within a comprehensive plan to transition Illinois to 100 percent renewable energy, including firm closure dates for nuclear and fossil fuel generation.

Instead, this legislation requires consumers to pay a subsidy for almost all the power these plants produce, at a subsidy level greater than the one passed while ComEd’s scheme was ongoing. This is not a targeted plan for a responsible transition to 100 percent renewable energy; this is a cash grab. The large, broad subsidy for Exelon in this legislation fails to protect the public interest.

Performance incentives

All regulation is incentive regulation. The performance metrics proposed in Section 8-514 will do little to nothing to change ComEd’s primary incentive to spend as much money as it can as fast as it can. Not a single proposed metric measures activity that would lower customer bills.

The proposed performance metrics would potentially slightly boost or slightly decrease ComEd’s ROE, or profit level. It’s critical to remember that the profit level is just one part of determining overall profits. The other is ComEd’s rate base, which grows as ComEd spends money. Even with a relatively low ROE, ComEd is already reaping record profits due to its massive spending over the last decade under formula rates. The financial incentives associated with the proposed performance metrics are small compared to ComEd’s overall profits. With small downside risk, the performance metrics provide ComEd another opportunity to boost its profits.

The legislation carefully creates a structure for the performance metrics: at least 9, no more than 11, with financial incentives of a total potential decrease of 70 basis points and a total potential increase of 60 basis points. It also carefully creates a major loophole to this structure. Subsection (e), starting on page 379, creates the opportunity to create an untold number of further metrics, outside of the structure of the others. Metrics created under the subsection only come with potential financial reward, no financial penalty. There is no limit to the size of the financial reward.

Finally, according to subsection (g) starting on page 380, the section does not require the Commission to review the utilities’ performance reporting. That is, a utility could report on its success or failure meeting metrics, and receive financial penalty or reward, without Commission review of the veracity of its reporting. If the Commission opts to investigate, it only has 60 days to review, only 40 percent as long as a short rehearing at the Commission.

Conclusion

If the General Assembly believes the policies passed during the ComEd bribery scheme were good but were not biased enough towards ComEd and Exelon — that consumers should be forced to pay more to get less — it should pass the policies contained in HB1472 HFA1.

In doing so, it should defend its position to Illinois voters rather than obscuring its intent by, among many other things, claiming to end formula rates while doing the opposite – reproducing formula rate’s worst aspects and making them more profitable.

Instead of doubling down the policy legacy of ComEd’s bribery scheme by passing this legislation, or including these policies in negotiated omnibus energy legislation, the General Assembly should restore meaningful public oversight of utility operations and profits, and recenter utility policy on maximizing the public good.

Again, thank you for the opportunity to testify today. I would be happy to answer questions from the Committee.

[1] The legislation appears to apply a percentile to a simple average, which is confusing. Past experience suggests utilities will use any lack of clarity in law to advocate for their greatest advantage.

Topics

Authors

Abe Scarr

State Director, Illinois PIRG; Energy and Utilities Program Director, PIRG

Abe Scarr is the director of Illinois PIRG and is the PIRG Energy and Utilities Program Director. He is a lead advocate in the Illinois Capitol and in the media for stronger consumer protections, utility accountability, and good government. In 2017, Abe led a coalition to pass legislation to implement automatic voter registration in Illinois, winning unanimous support in the Illinois General Assembly for the bill. He has co-authored multiple in-depth reports on Illinois utility policy and leads coalition campaigns to reform the Peoples Gas pipe replacement program. As PIRG's Energy and Utilities Program Director, Abe supports PIRG energy and utility campaigns across the country and leads the national Gas Stoves coalition. He also serves as a board member for the Consumer Federation of America. Abe lives in Chicago, where he enjoys biking, cooking and tending his garden.

Find Out More

Illinois PIRG 2024 Legislative Agenda

Dry cleaner with an electric clothes dryer

Need to replace your water heater? Consider electric