Protect public health workers and all Americans

Call on your Representatives in Congress to support more COVID funding for nursing homes.

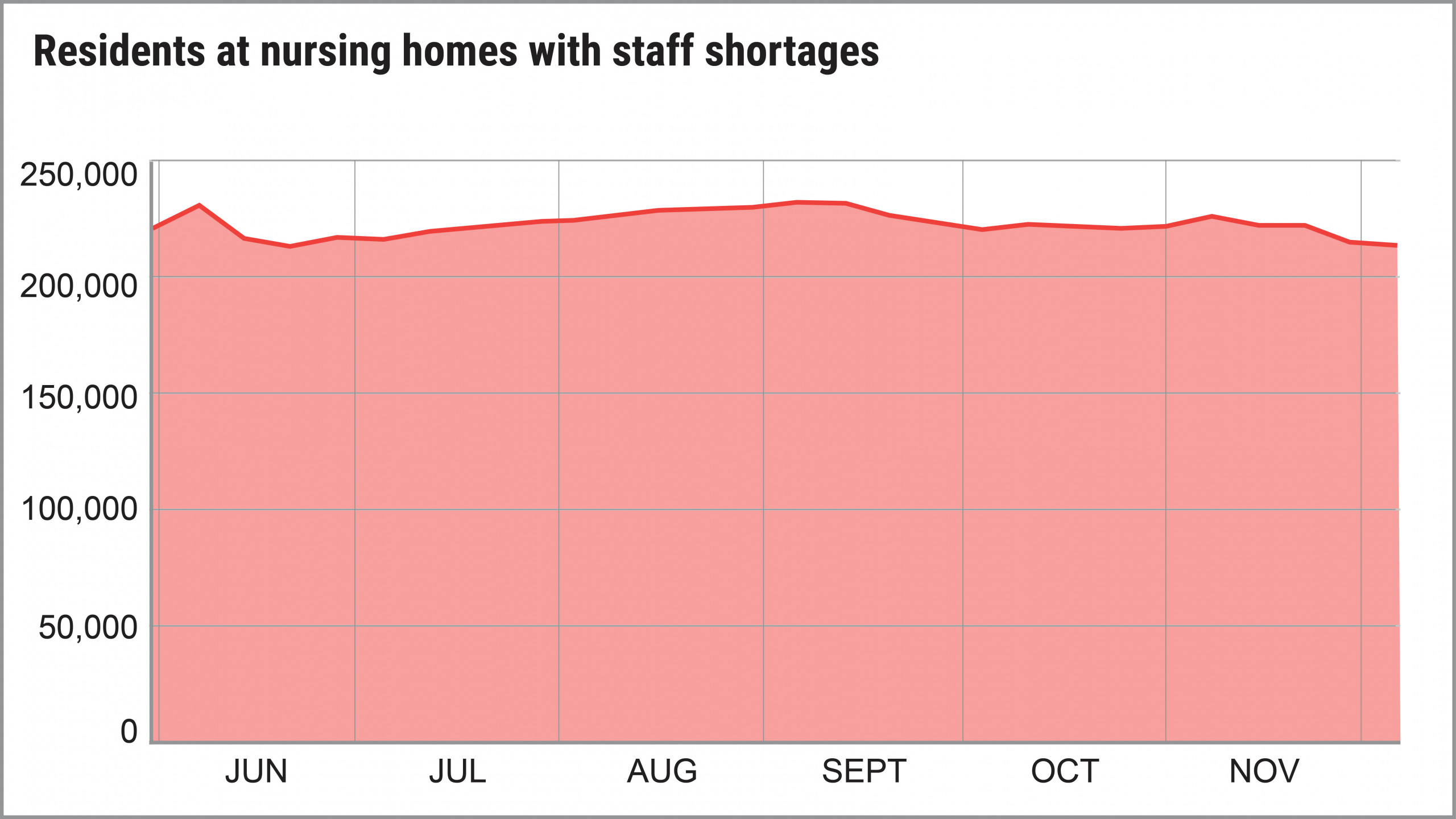

More than 3,000 U.S. nursing homes last month had a shortage of nurses, aides or doctors, and it’s a severe problem that has existed since last May. For most of last year, more than 200,000 people at any given time were in nursing homes that themselves acknowledged they were suffering from staff shortages.

A report created as part of a series by U.S. PIRG Education Fund and Frontier Group

By Teresa Murray, U.S. PIRG Education Fund, with data analysis by Jamie Friedman, Frontier Group

DOWNLOAD THE REPORT

More than 3,000 U.S. nursing homes last month had a shortage of nurses, aides or doctors, and it’s a severe problem that has existed since last May. For most of last year, more than 200,000 people at any given time were in nursing homes that themselves acknowledged they were suffering from staff shortages.

Source: U.S. PIRG Education Fund / Frontier Group analysis of data from data.CMS.gov

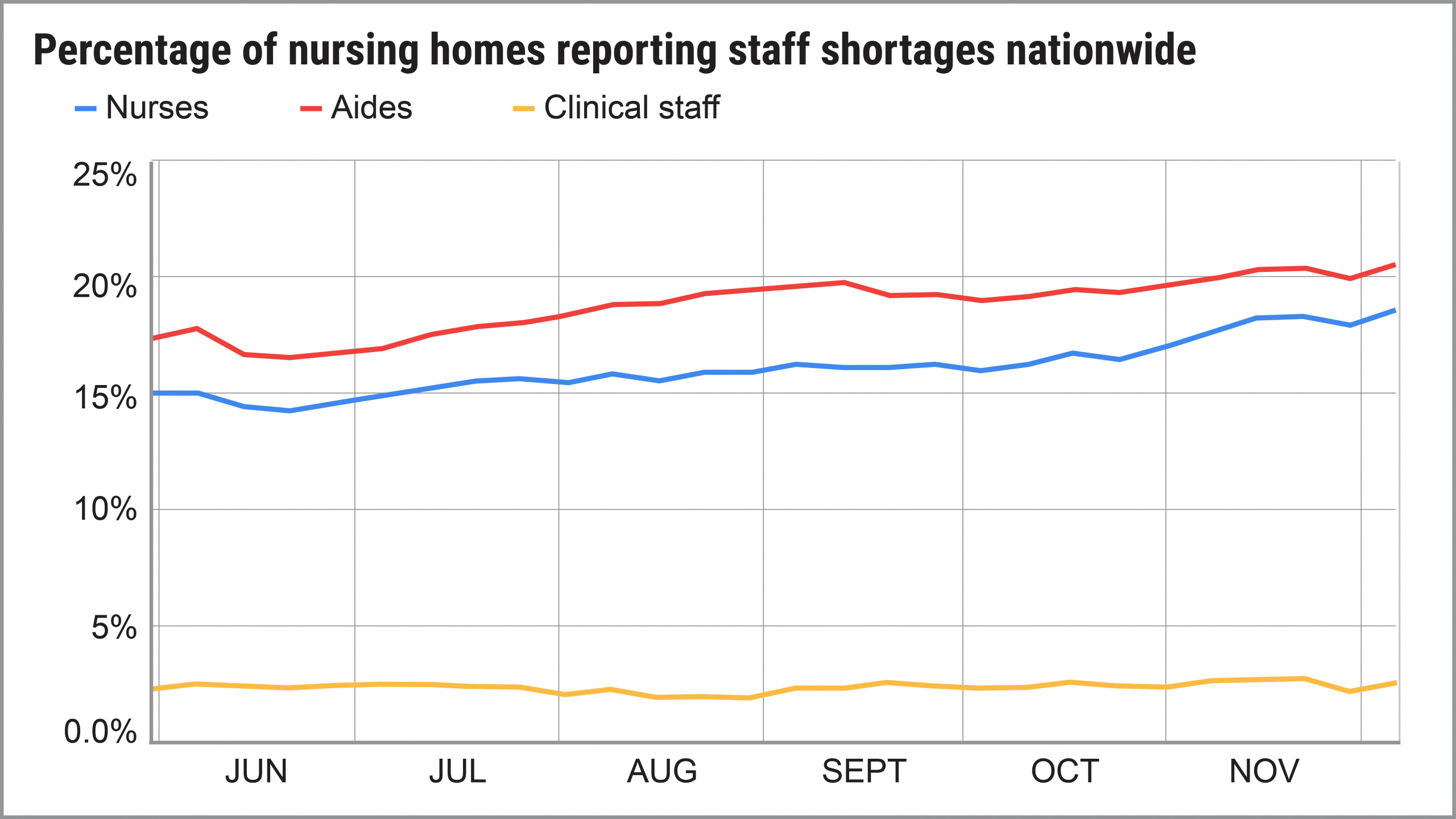

In fact, the number of homes reporting shortages of nurses, aides or clinical staff actually increased from May to December, according to an analysis of government data by U.S. PIRG Education Fund and Frontier Group. By early December, 23 percent of homes reported a shortage of at least one category of direct-care staff.

Not only are the shortages a direct result of the COVID-19 pandemic, experts say, but in a circular nightmare, the staff shortages also fueled more COVID outbreaks in nursing homes among residents and staff. More cases mean more stress for workers and more workers who contract the virus or are exposed, which then leads to even more staff shortages. The end result: In many cases, when there aren’t enough workers, patient care suffers.

All of this comes at the same time nursing homes are still grappling with shortages of masks, gloves and other supplies to protect everyone inside the homes from transmitting the virus. And they’re also trying to navigate shortages of COVID tests, a slow vaccine rollout and high levels of community spread in most parts of the country.

Nearly a year into this pandemic, all of these are crises that make every day challenging for nursing home residents and the people trying to care for them.

While there are encouraging signs with the arrival of vaccines, the problems facing nursing homes are snowballing, and the situation may erupt before the pandemic subsides, said Dr. Michael Barnett, assistant professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

“It’s a recipe for a collapse in the workforce,” Barnett said.

Source: U.S. PIRG Education Fund / Frontier Group analysis of data from data.CMS.gov

Key findings

It’s not surprising COVID-19 has ravaged nursing homes, given their unique issues: Residents are there 24 hours a day, the living quarters are tight, and people in nursing homes and rehabilitation centers are generally older and in poorer health than the population overall.

While nursing homes contain less than one-half of 1 percent of the U.S. population, they’ve produced 2 percent of the country’s COVID cases and 25 percent of deaths. The raw numbers: 522,516 nursing home residents diagnosed with COVID, 101,970 of whom died, as of mid-January. Then there are the workers: 448,389 cases reported among nursing home staff nationwide, resulting in 1,313 deaths.

Since last May, nursing homes have been expected every week to report to Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) nearly 100 pieces of data related to COVID-19, including diagnosed cases, deaths, tests, PPE shortages, and shortages of nurses, aides and clinical staff, which includes doctors.

At any point in time, there are about 1.3 million people with short-term rehabilitation needs or long-term illnesses who reside in the nation’s 15,000 nursing homes. During the period we examined, from May 31 through Dec. 6, shortages of nurses and aides grew more dire as the year went on:

Consequences of staffing shortages

When homes are short on staff, resident care suffers, workers face even more stress, COVID cases can spread faster and more staff quit.

“It makes everything harder,” said Barnett of Harvard. “There is a long literature documenting that facilities with higher patient/staff ratios have lower quality and worse outcomes, which applies to hospitals too.

“Stress is enormous. There is more work to do. It’s harder and there are fewer people,” Barnett added. “And residents are isolated, depressed and cognitively worsening.”

Rebecca Gorges, post-doctoral fellow at the Center for Health and the Social Sciences at the University of Chicago, said her research found that, among nursing homes with one or more COVID cases, they were likely to have fewer deaths and a lower probability of a severe outbreak if they had higher levels of staffing before the pandemic.

She believes staff shortages contributed to the spread of COVID in many homes and believes more staff means it’s easier for a home to adopt best practices, such as regular testing of residents and staff, and separating residents by COVID status.

At Harvard, Barnett’s research found that nursing homes that reported COVID-19 cases had higher staff shortages and bigger PPE shortages than homes without positive cases. “The magnitude of these shortfalls poses a major threat to public health,” the report said.

The nonprofit Center for Medicare Advocacy in Washington, D.C., said it reviewed four recent studies that used different databases, criteria, dates and states to conclude that “nursing facilities that have more nurses are more successful in containing coronavirus cases and deaths among residents than facilities with lower nurse staffing levels.”

There’s no doubt that staff shortages have negatively affected overall care, said Robyn Grant, director of public policy and advocacy at the nonprofit National Consumer Voice for Quality Long-Term Care of Washington, D.C., a consumer advocacy group. In its new survey, 87 percent of respondents indicated their loved one’s physical appearance had declined last year and 85 percent said their loved one’s physical abilities had declined.

Among staff, the stress of working in a nursing home during COVID has been crushing for many: There’s illness among residents, phone calls from families who can’t visit, residents who are incredibly lonely and beg for your time, residents who have no one besides you to hold their hand as they die, and the constant fear of contracting the virus, particularly in homes without enough PPE.

“COVID-19 is taking a considerable toll, physically and emotionally, on our health care heroes in long-term care,” said Dr. David Gifford, chief medical officer at American Health Care Association and National Center for Assisted Living (AHCA/NCAL). “Burnout is a real concern for all health care workers during this pandemic.”

The stress likely leads to more staff turnover, said Gorges of the University of Chicago, and then more COVID cases.

Why staff shortages got worse

Worker shortages in nursing homes didn’t start with the pandemic.

To paint the picture of shortages before the pandemic: Experts recommend 4.1 hours of direct care per resident per day, according to Consumer Voice. In the fourth quarter of 2019, it was 3.37 hours.

When the government began collecting data from nursing homes in May, the pandemic was raging and so were staff shortages, with 2,790 homes reporting a shortage in at least one staff category. That grew as the year went on, increasing to 3,136 homes in December.

The pandemic both exposed and made worse the existing problem of staff shortages in nursing homes. The long-standing staff shortage problem is beyond the scope of this report, but there are several ways that COVID made this problem even worse, such as:

Gorges said the statistics among staff are haunting: As of mid-January, there have been 448,389 COVID-19 cases reported among nursing home staff nationwide, resulting in 1,313 deaths.

“Working in a nursing home is now one of the most dangerous jobs in America,” she said.

A big factor: Workers still don’t have enough PPE, according to the Service Employees International Union, which represents many staffers. New research by U.S. PIRG Education Fund and Frontier Group shows shortages of most types of PPE decreased significantly during the fall months, but increased during December.

How nursing homes are coping with shortages

Nursing homes are dealing with staff shortages in a number of ways:

What needs to be done

This problem is urgent. “Unless these shortages are prioritized by policymakers, long-term care residents will continue to be at a great disadvantage in the pandemic,” the report from Harvard said.

Among the solutions that are needed:

Call on your Representatives in Congress to support more COVID funding for nursing homes.

Sign Up

Video guides

How to find information (PPE shortages, staff shortages, outbreaks, etc.) about a specific nursing home.

How to look up all nursing homes in a particular city, zip code.