Distorted Democracy: Post-Election Spending Analysis

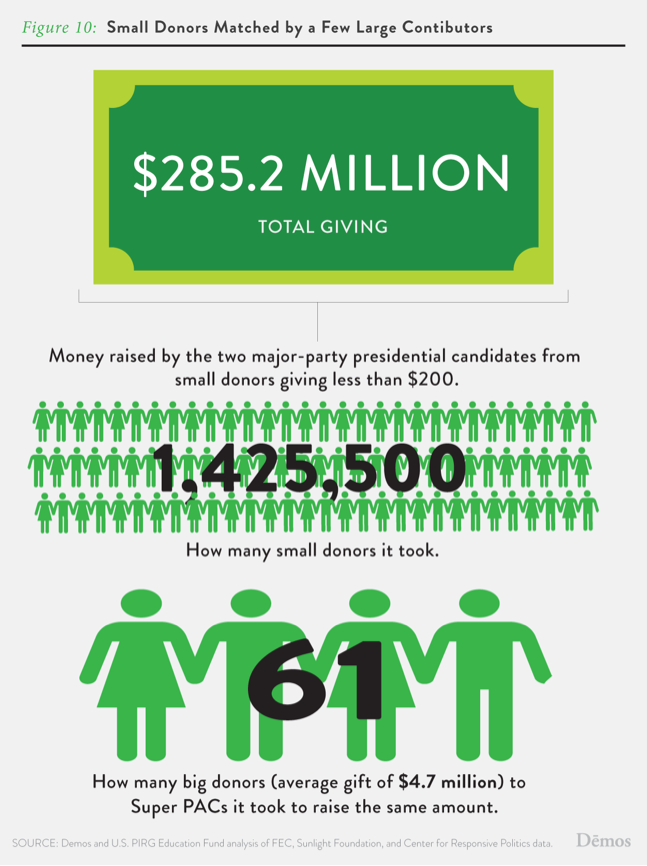

A new analysis of data through Election Day from the Federal Election Commission (FEC) and other sources by U.S. PIRG and Demos shows how big outside spenders drowned out small contributions in 2012: just 61 large donors to Super PACs giving an average of $4.7 million each matched the $285.2 million in grassroots contributions from more than 1,425,500 small donors to the major party presidential candidates.

Downloads

A new analysis of data through Election Day from the Federal Election Commission (FEC) and other sources by U.S. PIRG and Demos shows how big outside spenders drowned out small contributions in 2012: just 61 large donors to Super PACs giving an average of $4.7 million each matched the $285.2 million in grassroots contributions from more than 1,425,500 small donors to the major party presidential candidates.

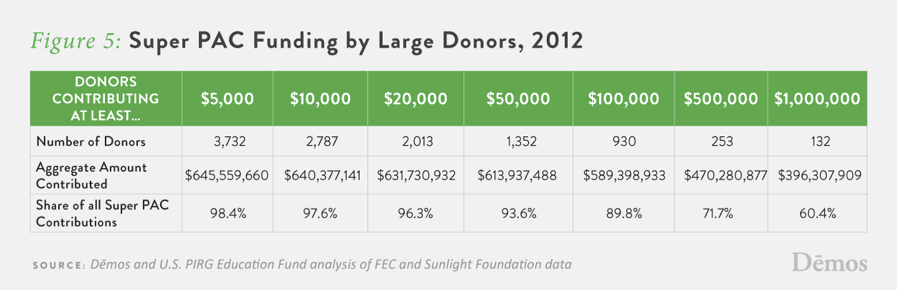

In addition, the analysis found that just 132 donors giving at least $1 million were responsible for 60.4% of all the money Super PACs raised in the 2012 cycle. $71.8 million of Super PAC money came from for-profit businesses.

This evidence shows that the first post-Citizens United election afforded corporations and large donors the opportunity to use their wealth to amplify their voices far beyond the volume of the average member of the general public – threatening the basic American principle of political equality – and they took full advantage.

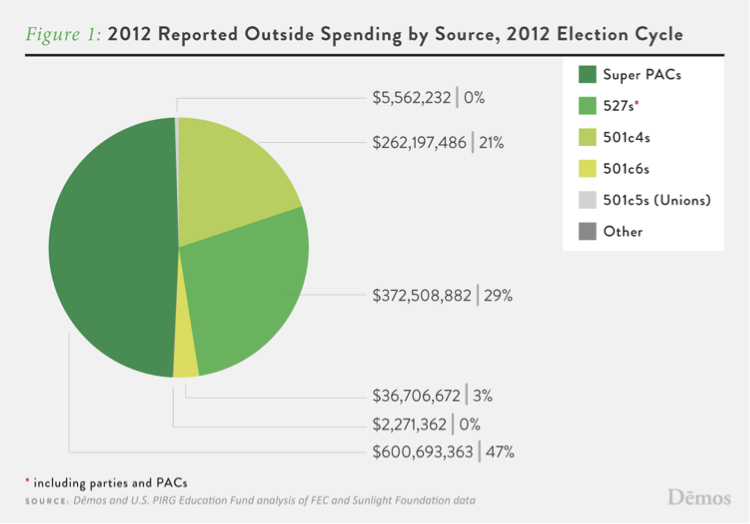

Outside spending organizations reported $1.28 billion in spending to the FEC through the end of Election Day 2012.

Large Donor Dominance

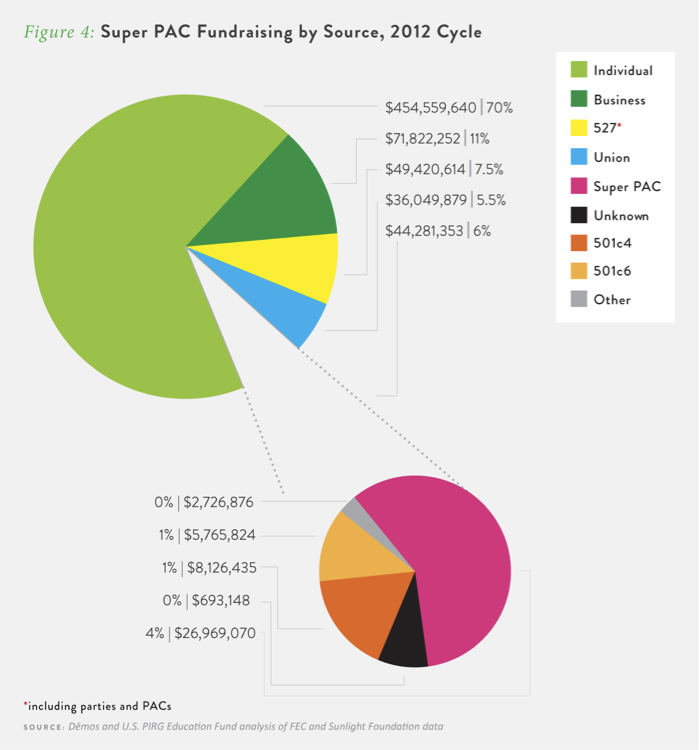

Almost half of all reported outside spending comes from Super PACs, the independent expenditure-only committees created in the wake of Citizens United. Super PACs continue to receive the bulk of their funds from a small set of wealthy donors and corporations making very large contributions.

$396 million, or 60.4% of the $656 million raised by Super PACs, came from just 132 donors giving at least $1 million.

Fewer than 2,800 donors giving $10,000 or more were responsible for 98% of this fundraising.

Policy Recommendations:

The only way to stop the flow of unlimited money into our elections and the best way curb the influence of large donors is to overturn the “money equals speech” precedent in the 1976 Buckley v. Valeo decision, either by constitutional amendment or by Supreme Court revision.

Small Donors v. Large Contributors

The two major party presidential nominees have reported raising a combined total of $285.2 million from small donors giving less than $200 according to the Center for Responsive Politics, which came from at least 1,425,500 individuals. Just 61 donors (individuals and institutions) giving an average of $4.7 million each to Super PACs matched the total contributions of these small donors.

Because of their wealth and the Supreme Court’s equation of money with speech, those very large donors are able to amplify their voices to more than 23,000 times the volume of an average small donor.

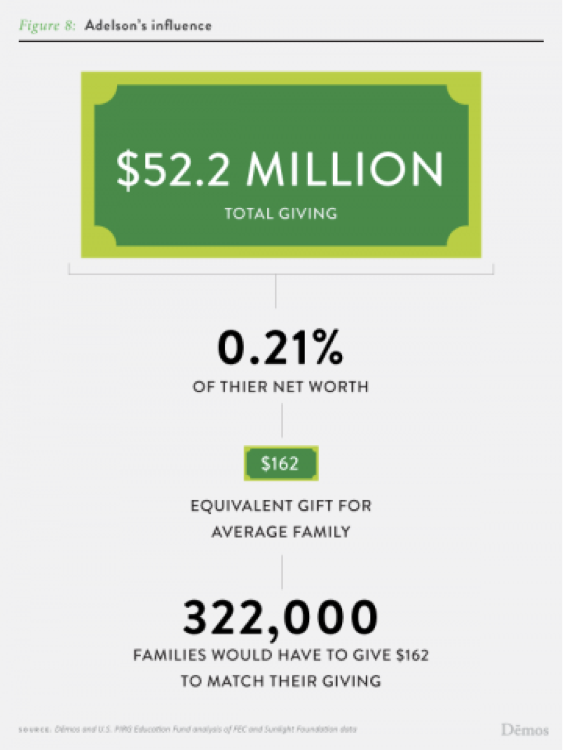

Sheldon and Miriam Adelson, have given $52.2 million to Super PACs in the 2012 cycle, which, though a significant sum, is just 0.21% of their net worth. It would take more than 322,000 average American families donating an equivalent share of their wealth ($162) to match the Adelsons’ giving alone.

Policy Recommendations:

Short of the aforementioned constitutional amendment to allow for the democratic establishment of reasonable contribution and spending limits, there is much to be done to encourage the increased participation of small donors to balance out the big money.

A system of tax credits for small contributions to federal candidates was in place through the mid-eighties and should be restored. Vouchers for small contributions would also significantly increase donor participation among non-wealthy Americans. Matching small contributions with public funds would help candidates focus their campaign time on constituents, rather than big donors.

Business Money to Super PACs

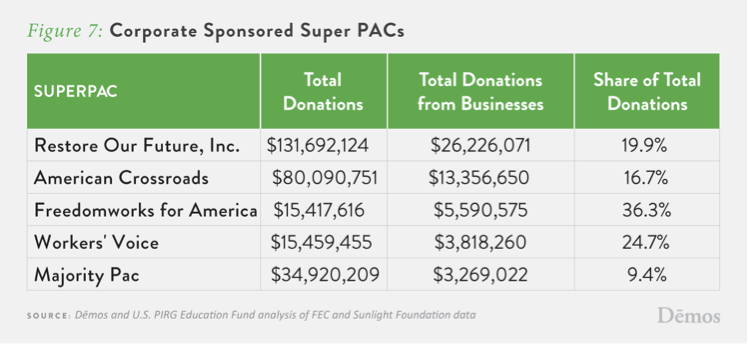

While it is likely that much of the business money coming into the elections was funneled through dark money sources such as the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which spent at least $36 million on races nationwide according to the Center for Responsive Politics, business corporations remain the second largest source of Super PAC money, accounting for $71.8 million, or 11% of all Super PAC funds.

Some of the largest and most active Super PACs receive a significant portion of their funding from businesses: pro-Romney Restore Our Future received 20% of its funds from for-profit corporations.

Polling released in late October revealed that 84 percent of Americans agree that corporate political spending drowns out the voices of average Americans, and 83 percent believe that corporations and corporate CEOs have too much political power and influence.

Policy Recommendations:

Corporations do not have the same rights as individual human beings and should not be allowed to spend money from their general treasuries in elections. Allowing a CEO or corporate board to direct funds aggregated from commercial enterprise to support or a candidate or cause fundamentally skews our democratic process and favors the profit imperative above all else. The only way to prevent this entirely is to overturn the Supreme Court’s decision in Citizens United, either by constitutional amendment or Court revision.

Until we reverse Citizens United, Congress should empower shareholders at corporations to have final say on whether the corporations they own may spend money in elections, thereby creating a minimum system of people-powered checks and balances on business money in politics.

Dark Money

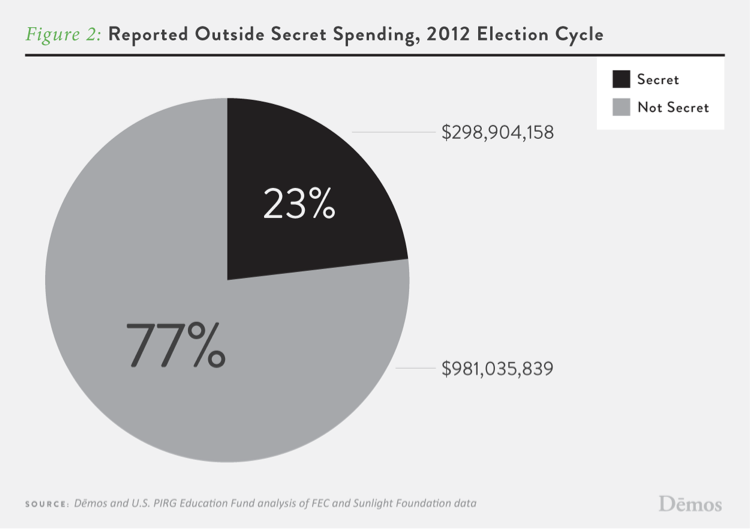

Of the $1.28 billion in outside spending reported to the FEC, nearly one-quarter, or $298.9 million, was “dark money” that cannot be traced back to an original source.

Americans across the political spectrum have long held transparency in campaign funding to be crucial. When citizens can’t follow the money voters can’t judge the credibility of political communications and corporations and other special interests can fund misleading advertisements without facing accountability.

Policy Recommendations:

Congress and the states should enact laws that create transparency and allow Americans to trace every penny spent on elections back to an original source.

The Securities and Exchange Commission should issue a rule requiring publicly traded corporations to disclose their political spending to their shareholders, both direct spending and gifts to politically active trade associations such as the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, so that at the very least investors know when their money is being used to support causes they oppose.

Last month, new polling found that 76% of Americans support a requirement that companies publicly disclose their contributions to groups like the U.S. Chamber of Commerce that funnel their money into politics.

Doubly-Secret Money

Because of gaps in reporting requirements, spending reported to the FEC is only part of the picture. Groups are not required to report to any public agency certain spending that is intended to influence an election but falls outside of certain time windows before that election.

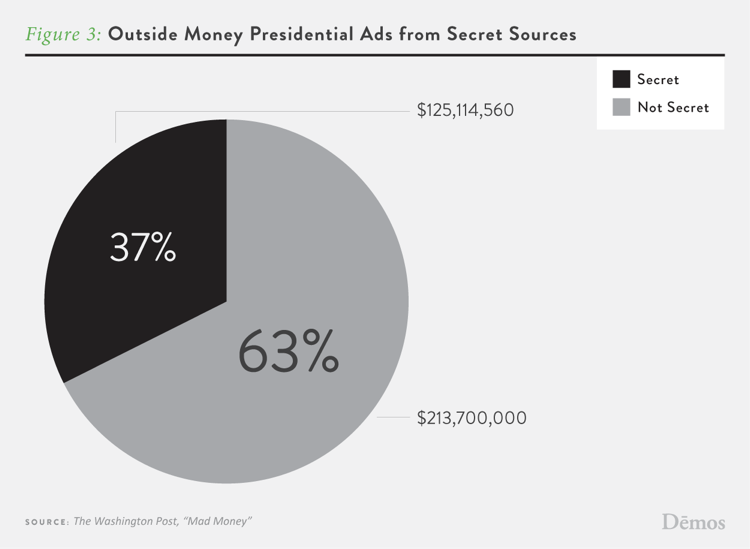

However, there are a few races where complete spending information is available from private sources. These may give us a sense of the discrepancy between what was reported and what was actually spent by dark money groups. For example, when all types of outside spending on television ads related to the presidential race are taken into account, 37% of the spending has come from by “dark money” groups that do not disclose their donors.

Policy Recommendations:

To begin to understand the full scope of dark money in elections, Congress must expand the electioneering communications window, which presently only captures spending two months before generals and one month before primaries, to reflect the true length of modern elections.

Conclusion

It is clear that unlimited, corporate, and secret money continues to undermine the principle of ‘one person, one vote.’

Never before last Tuesday has big money had such a large profile in a national election, and the voters spoke clearly: we rejected the premise that elections are auctions and that democracy is for sale.

In the cities and states with direct referenda on money in politics, the electorate’s stance was clear: Colordans rejected unlimited money in elections with 73% of the vote. Montana, which went overwhelmingly red in the presidential election, passed a resolution shooting down the dual notions that money is speech and corporations are people by a margin of 50 points (75%-25%), proving that this issue bridges partisan divides. Voters in towns all over Massachusetts and in Chicago and San Francisco also passed ballot initiatives pushing back on the avalanche of big, special interest money.

Polling over the last few months confirms the premise that Americans’ awareness of the problems associated with corporate and unlimited money in our politics has reached new heights: seven out 10 Americans believe that Super PACs should be illegal and nine out of 10 believe that corporations have too much power in our political process.

Furthermore, many of the winning campaigns facing massive Super PAC and dark money opposition made big money in politics an issue, which turned the tables and transformed big spending into a double-edged sword.

All this could not have been accomplished without heavy media attention on the issue of big money. Unfortunately, some in the media have now begun to embrace the notion that the big money didn’t matter, looking for the simplest story of a correlation between cash and victory, which fundamentally misses the point.

This narrative on campaign finance is misguided. Allowing the wealthy few to amplify their voices in the public square threatens the basic American value of political equality for several reasons:

First, a tiny number of wealthy individuals and interests continue to set the agenda in Washington and in state capitals across America. Second, down-ticket races are easier to buy than high-profile presidential and senate contests where there is plenty of media coverage and general awareness of candidates and their positions. Third, large donors and big spenders enjoy preferred access to and influence over winning candidates—giving them another, direct chance to shape the agenda in Washington and state capitals across America, and undermining citizens’ confidence in our democracy. Fourth, the threat of massive outside spending is ever-present, shaping candidate behavior and forcing them to spend time on a high-stakes arms race rather than engaging voters or actually governing (in the case of incumbents).

The narrative also puts America in a Catch-22: according to some, if money in politics is really a problem, then the candidates with the most financial backing will always win. But in that scenario, those who rode into office on a wave of money will never vote for reforming the system that elected them. On the other hand, if there is not an unquestionable correlation between victory and outside spending, then maybe we’ll have elected legislators willing to tackle reform, but some will argue there is no problem with unlimited money in the first place.

We see it differently: rather than seeing Tuesday’s results as an indicator that big money in politics is not a problem, our freshly elected legislators, in particular those who fought back against special interest outside spending should see the results as a mandate for reform.

We hope the figures and policy recommendations in this analysis can provide a roadmap for the changes needed to build a campaign finance system grounded in democratic principles.

This is the fourth release in the PIRG and Demos series of analyses on the role of money in the 2012 elections. Previous reports are available here, here, and here. Today’s release shows the overwhelming influence of a tiny number of wealthy donors. The organizations plan to release a comprehensive analysis of 2012 election fundraising and spending in January 2013.