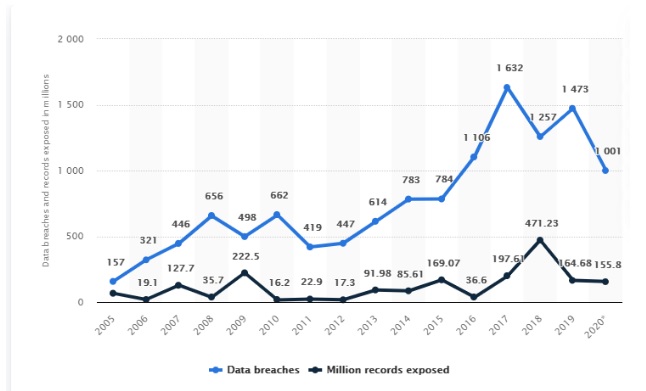

Credit: Statista, “Annual number of data breaches and exposed records in the United States from 2005 to 2020 (in millions)”

Our personal data is important and should stay private. We shouldn’t have to risk our personal information being stolen because we want to visit a website or sign up for a rewards program. We should be able to control where our data goes and who has access to it. We need data privacy.

Two different data privacy paths to go down but only one right path

Lawmakers at the state and federal level should be applauded for considering data privacy policies, but in the rush to pass something, we risk going down the wrong path and making true data privacy even harder.

On a federal level since 2019, the adtech industry, which represents the companies that want us to have as little control as possible over our own data, has been lobbying for a weak federal data privacy law.

On a state level, California and Virginia have already passed different versions of data privacy laws. Other states, like here in Colorado and New York, are considering them as I write this.

Ultimately, there are two paths you can take to enact a data privacy law:

- You can enshrine the current system where companies automatically get access to your data and consumers must play an endless game of whack-a-mole trying to identify and stop data collecting and sharing using an “opt-out”-based law.

- You can put people at the center of the policy and pass a law that requires companies to ask you upfront if they can track, sell and share your data using an “opt-in” law. This also gives you more control over what and how much to share.

An “opt-in” law and system is much better for consumers and takes us down the right path that builds the right foundation for ultimate data privacy, but unfortunately, it is the path less traveled by states and the federal government.

Here in Colorado, our legislature is considering an “opt-out” bill, meaning that companies get access to our personal data unless we tell them to stop. Furthermore, the bill, SB21-190 titled Protect Personal Data Privacy, only lets consumers opt-out of data collection, tracking, selling and sharing for a few purposes.

This means that few things will actually change around data privacy in Colorado. We’re enshrining the wrong foundation into law, and the bill will make future data privacy gains harder to achieve.

Looking at who’s in support of this bill reinforces that we’re headed down the wrong path. The entities that benefit from the collection and sale of our personal data, and ones that aren’t good at keeping our data safe, support this bill according to a review of Colorado’s lobby disclosure database.

One part of the bill says companies should have a “clear and conspicuous” way to let you know how to opt-out of getting your data collected. That sounds nice. But in practice, the most clear and conspicuous way to ensure people know what’s being collected and how it’s being used is an opt-in system in which we get to choose up front.

Despite Colorado going down the wrong path other states are considering legislation that will center the consumer and data privacy.

New York is considering a data privacy bill that would require companies to get consumers to opt-in to having their data collected, tracked, sold and shared. And their bill would allow consumers to sue companies that collect their data if they don’t want their data collected. This bill is the right path to take and lays a much stronger foundation for data privacy.

There’s a sense of urgency that data privacy needs to be addressed right now, and that passing a law, no matter how good or bad it is, is better than leaving the situation alone. I often agree and advocate for that incremental approach. But not here.

Although it may seem like passing a bill is better than passing no bill, this bill is not a step forward. We are digging a deeper hole and making it harder to tackle this issue in the future. There is a better way.

We may not have the time to pass the right bill this legislative session in Colorado. But waiting to pass the right bill will be worth it. We need to lay the right foundation for data privacy in Colorado.