Matt Wellington

Former Director, Public Health Campaigns, PIRG

In the spring, we shut down our lives and our economy in hopes of reducing the spread of COVID-19 enough to be able to manage it through widespread testing and contact tracing. In spite of that shutdown, today the virus is raging virtually uncontrolled. We didn’t stick with it until the job was done.

Former Director, Public Health Campaigns, PIRG

The United States has the highest coronavirus death toll in the world.

It didn’t have to be this way — and in most developed countries, it isn’t. Countries like Germany, Singapore, Australia and Japan have fractions of our death rate.

If our response had been as effective as Germany’s, we would have had only 36,000 COVID-19 deaths by mid-June in the United States, instead of 117,000. If our response had been as effective as South Korea, Australia or Singapore’s, fewer than 2,000 Americans would have died by then. We could have prevented 99% of those COVID-19 deaths. But we didn’t. And today, the number of coronavirus-related American deaths has passed 170,000.

How did this happen?

In the spring, we shut down our lives and our economy in hopes of reducing the spread of COVID-19 enough to be able to manage it through widespread testing and contact tracing. In spite of that shutdown, today the virus is raging virtually uncontrolled. California recently declared defeat on the whole concept of contact tracing, because there are too many cases to trace. Other states are quite obviously in the same situation.

Was shutting down the wrong approach?

Clearly not. It worked in other countries. So what went wrong here?

We didn’t stick with it until the job was done.

Given our current situation, a shutdown that succeeds in suppressing the spread of the coronavirus is both the best way to save lives and the fastest way to start moving safely back toward social life.

But a shutdown is only effective if it lasts long enough and is comprehensive enough to interrupt transmission of the virus. An effective shutdown reduces the total number of infected people to the point where cases are rare enough to monitor and contain. Then, robust testing and contact tracing are critical to containing isolated outbreaks before they explode.

Public health experts have identified two key indicators for when it’s safe to lift a shutdown:

The rate of new daily cases should be less than 1 per 100,000 people in the population.

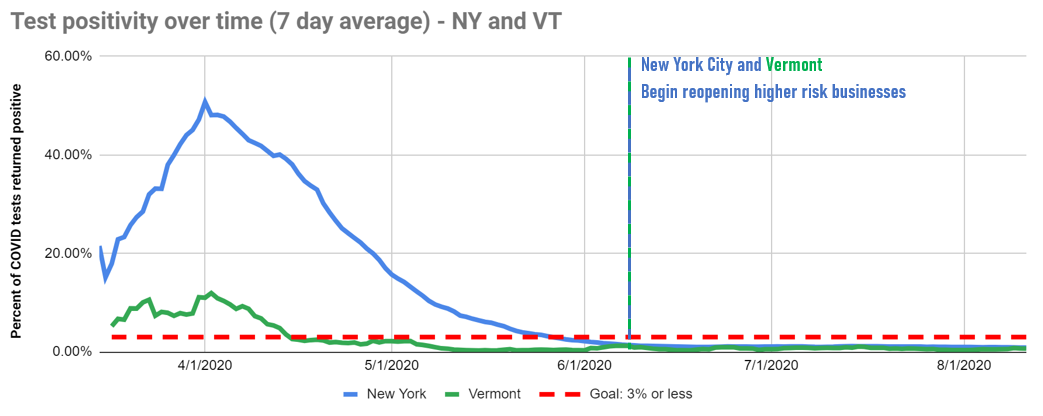

Less than 3% of people tested should have a “positive” test result. At that level, we can effectively trace new cases and contain new outbreaks.

That second indicator assumes that we are doing a lot of testing — enough to get a true picture of what is going on. Harvard’s Global Health Institute has said that to squelch the virus, we’d need to process about 4.3 million tests per day — which unfortunately is a staggering goal due to federal inaction to increase our capacity to create, ship, administer and evaluate COVID-19 tests.

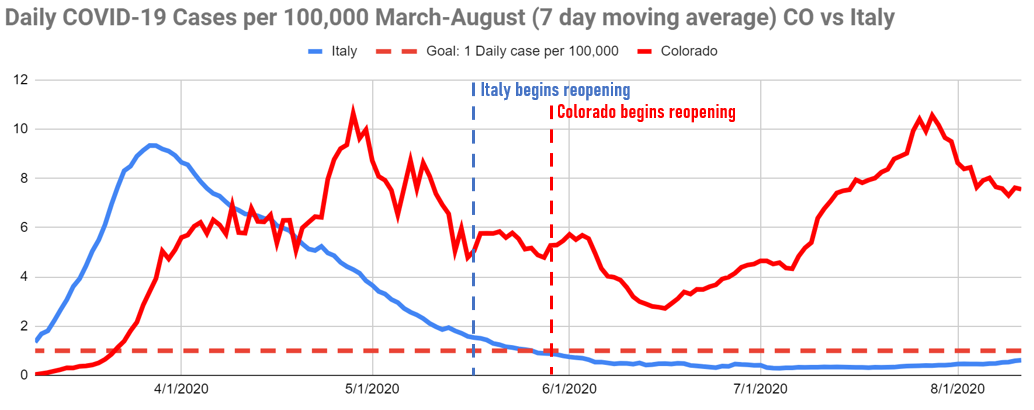

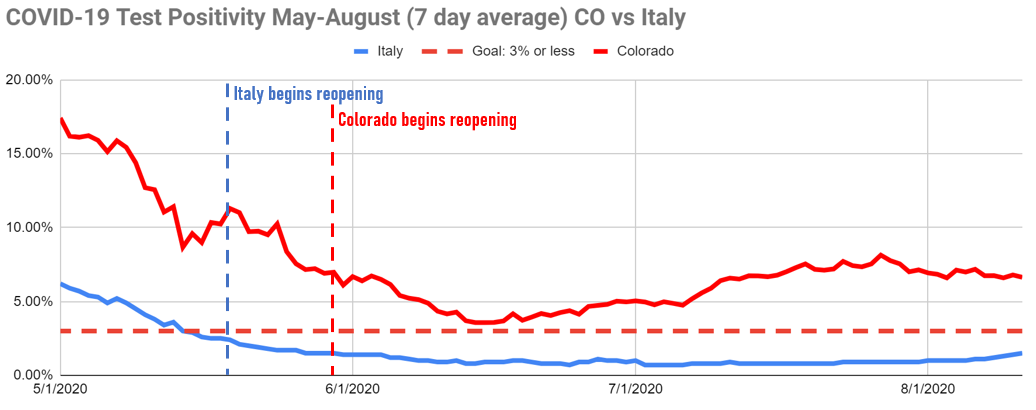

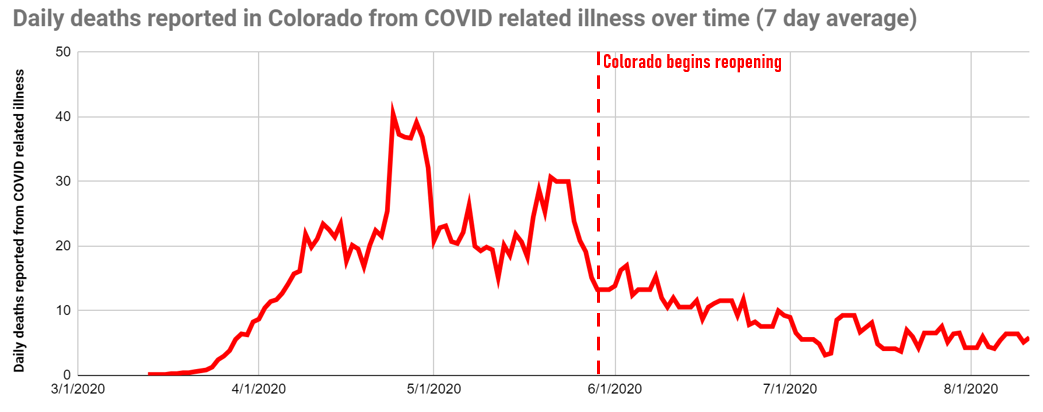

Using those key indicators, let’s look at what has happened in Colorado. COVID-19 case growth was slow in our state until late May, when the state began lifting restrictions on high-risk businesses on the 27th.[i] The effects of reopening became clear about three weeks later, as case growth exploded, eventually reaching an average of 10 per 100,000 per day.[ii] That’s 10 times higher than the target.

Our daily average cases peaked above the daily average case rate in Italy in mid-March, when that country was the epicenter of the outbreak in Europe.

In contrast, Italy’s emergence from shutdown, which started several weeks before ours, was much more successful. Adherence to the guidelines for daily cases and positivity rates resulted in a far better outcome.

These charts tell the story:

Our state failed to follow the guidelines — we reopened before cases had fallen to containable levels, and we lacked enough testing to track the spread. While limiting bar hours, increased adherence to public health guidance, and widespread mask use have all helped bring new infections down over the last month, COVID-19 is still spreading widely. This time, we must not relax restrictions until the virus is under control.

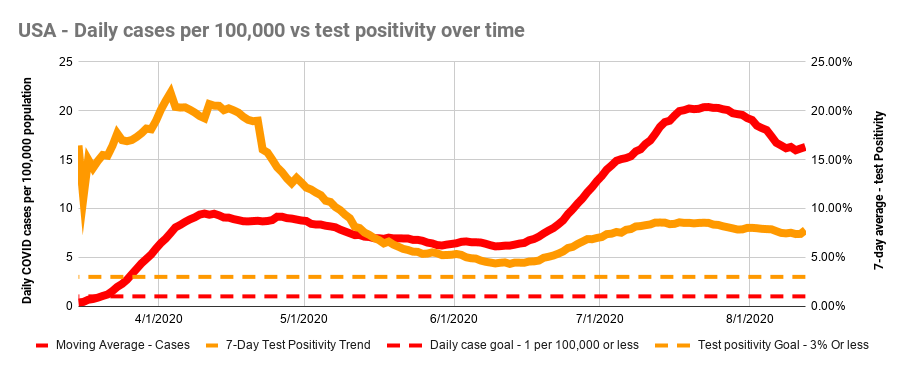

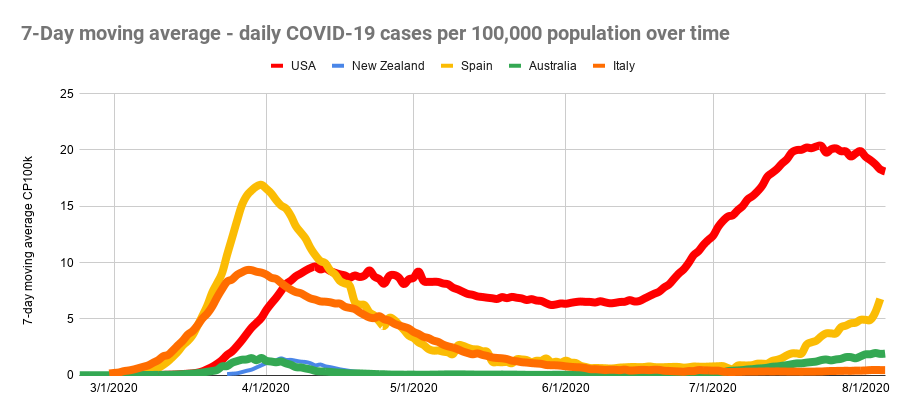

The overall American experience is reflected in this chart:

Nationwide, the positivity rate went down until mid-June (roughly four weeks after many states began “loosening” restrictions), but the rate never hit the recommended threshold. Likewise, widespread shutdowns initially brought daily cases down significantly, but reopenings started before the cases hit the recommended threshold, and then the case numbers shot upward.

In contrast, successful shutdowns in other countries crushed their infection curves. In those countries, the indicators flatlined before reopening started.

New Zealand didn’t end its shutdown until the country had less than .02 daily cases reported per 100,000 people and a test positivity rate of 0.1%.

Italy didn’t end its shutdown until it reached a daily case rate of 1 per 100,000 people and 2.5% test positivity.

South Korea didn’t end its shutdown until daily cases per 100,000 people were below 1 and it had a 0.2% test positivity rate. (South Korea also quickly reimposed restrictions a week later following an outbreak connected to Seoul’s nightlife,[iii] as did Auckland, New Zealand, this week, following an outbreak of 4 cases.)

Data from Our World in Data COVID-19 Dataset.

In the United States, in many places we didn’t have strict enough shutdowns in the first place. And even in places where we DID adequately shut down, we didn’t stay shut down long enough to control community spread.

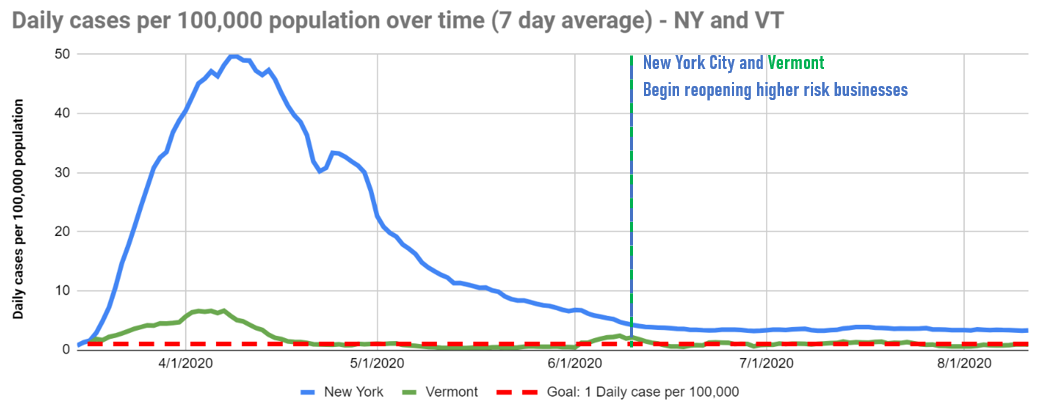

The U.S. states that have thus far succeeded in containing COVID-19 brought at least one of the key indicators below the recommended threshold (less than 1 new case per 100,000 of population, and a positivity rate of less than 3%) before loosening restrictions.

While New York began lifting restrictions in the New York City region with cases per 100,000 still above 4, test positivity was 1.6% — indicating the state was testing enough to track and contain new outbreaks.[iv]

Vermont reopened with 1.2 daily cases per 100,000 and 0.78% test positivity.

Even in light of these promising results, New York City has prudently decided not to reopen bars or indoor dining yet.

State leadership has been insufficient in many places, including here in Colorado. But the complete absence of federal determination to stop COVID-19 has set the stage for our national failure. The federal response to this disaster has been to let the states fend for themselves, leaving us with insufficient capacity to meet the imperatives of testing and contact tracing, as well as a piecemeal strategy in a nation of open borders. Not a recipe for success when you are trying to stop an invisible enemy that could be carried by any resident, anywhere.

Since we began reopening, dozens of people have died each week in Colorado from COVID-19, and most of those deaths could have been prevented. Many more are falling ill with this fearsome disease. And the needless deaths and suffering will only continue, until Colorado brings down its level of infections and our chart starts to look like those of the many countries that suppressed the coronavirus. Even then, there is no on-off switch for dealing with COVID-19. It will take diligent, steady leadership to save lives, with leaders acting quickly and sometimes making hard decisions to close higher-risk activities and businesses, as the indicators demand.

We need to shut down, start over and do it right this time.

[i] Due to the diversity of approaches taken by U.S. states, we’ve tracked the date that restrictions were lifted on high-risk businesses like restaurants, bars and retail stores for the purposes of this analysis. We have not taken into account changes to restrictions on personal service providers, outdoor recreation areas, and personal gatherings — which may have been loosened sooner or later depending on the state. We are using dates compiled by the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center, at https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/state-timeline.

[ii] Case counts and test positivity for U.S. states calculated using data from the COVID Tracking Project, retrieved on 8/11/2020, calculated as a 7-day (trailing) moving average, and adjusted by population using projections from the U.S. Census for 2019. Calculations are reflected in this google sheet: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1MwUHgvwAqmNVSvX0Wcn_87Z1s6CgVXZ7GHw8jYFoMAI/edit?usp=sharing Test positivity for Colorado calculated using data compiled by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, with calculations reflected in the following spreadsheet: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/15XJr2MgiRrvvxcmYZiH0djDTabPBHwKnyehdfag6udE/edit?usp=sharing

[iii] Case counts and test positivity for countries calculated using data from Our World in Data COVID-19 dataset, retrieved on 8/5/2020, and adjusting reported cases per million by a factor of ten to generate daily cases per 100,000 as a 7-day (trailing) moving average.Calculations are reflected in this google sheet: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/19E_xwOCtW0j39FZKf_KqFw_Ufm-cGFKH5RntAoR394o/edit#gid=0

[iv] Case counts and test positivity for U.S. states calculated using data from the COVID Tracking Project, retrieved on 8/11/2020, calculated as a 7-day (trailing) moving average, and adjusted by population using projections from the U.S. Census for 2019. Calculations are reflected in this google sheet: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1MwUHgvwAqmNVSvX0Wcn_87Z1s6CgVXZ7GHw8jYFoMAI/edit?usp=sharing

Photo of traffic light on red: Kevin Payravi, Wikimedia Commons

Former Director, Public Health Campaigns, PIRG