Small dollar donors are winning! (for now)

Small donors finally are gaining a meaningful voice in our presidential primaries. Political and cultural developments mean that it is NOT always more expedient to rely on big money to fund a presidential campaign. While it is still early in the 2020 campaign, this is a trend worth noting and, for now, celebrating.

The heated partisan rhetoric and record number of candidates in the early phase of the 2020 presidential election has obscured a major transformation in the process: the rise of the small-dollar donor! Candidates for our nation’s chief executive post are touting not just how much money they have raised, but how many contributions they are receiving, and, more significantly, how many of those donors are giving small amounts of money. Our elections should be driven by the interests of small-dollar donors (and the regular Americans who provide them), as opposed to big-moneyed interests. Now, a combination of technological and cultural changes are making that dream a reality in the United States’ biggest election.

As the numbers show, big money (and the people with access to it) have the biggest say in who gets to run for office. Campaigns are incredibly expensive. In 2004, the major party presidential nominees raised an average $348 million; by 2012, that number had ballooned to $586 million. To raise that kind of money, candidates must court mega-donors or corporate interests. As a result, the small number of people who have big money effectively decide who can run for office. The rest of us are relegated to choosing from among the winners of this “money election.”

Thanks to a series of misguided Supreme Court decisions, the problem of big money in politics has been getting worse since the 1970s. Buckley v. Valeo (1976) undid campaign spending limits. Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (FEC) (2010) ruled that money is speech and corporations are people, opening a new avenue for big money. McCutcheon v. FEC (2014) removed aggregate giving limits and further opened the floodgates.

We should have reasonable spending and contribution limits, but given the Supreme Court’s rulings, that’s out of the question for the foreseeable future. While advocates are working toward a constitutional amendment limiting money in politics, that project could take a long time. In the interim, we’re working on other solutions, such as small donor empowerment programs, to try to move our democracy towards the principle of one person, one vote.

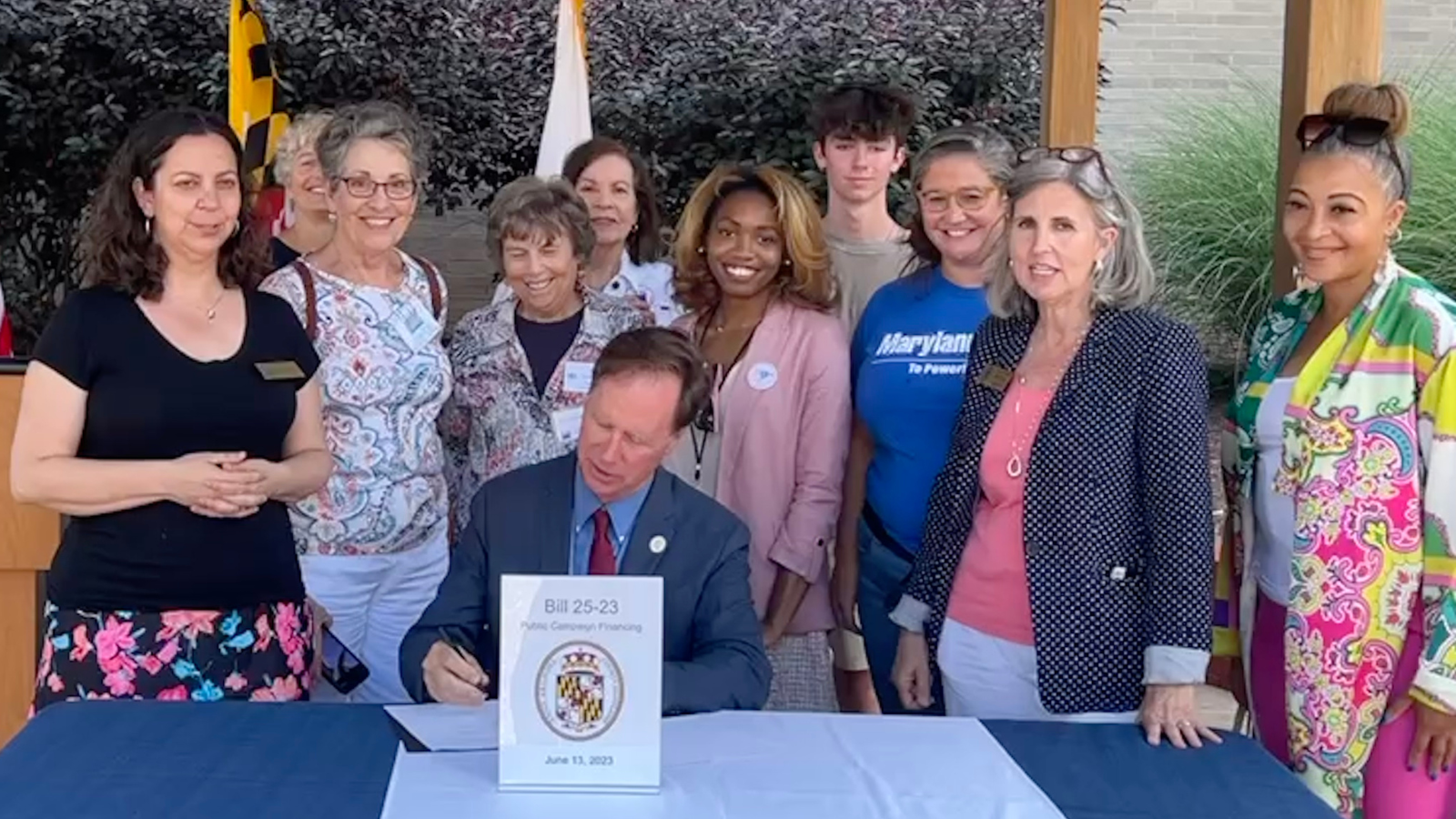

Small donor empowerment programs create a mechanism and incentives for candidates to eschew big money by matching ordinary people’s small contributions with public funds. Candidates access these funds when they opt into the program and refuse to take large and corporate contributions. As a result, candidates earn viability by building a base of support among average voters instead of moneyed interests. New York City has been using a system like this since the 1990s and in the last decade, communities from Maryland to Colorado have adopted similar systems. Efforts to establish a federal small donor matching system have not not yet been successful. However, if the trends of the 2020 race continue, it may not even be necessary for presidential campaigns.

In the 2020 presidential race so far, despite the lack of incentives and all the systemic advantages in favor of big money, we’ve seen a huge uptick in small donor giving. People of all political stripes are choosing to engage in political giving and make their voices heard. From January 1, 2019 to June 30, 2019, 51 percent of all funds raised from individuals for the 2020 presidential race came in contributions of $200 or less. This is encouraging, especially compared to recent history. In the 2008 presidential election only 20 percent of the money raised came from contributions of less than $200. In the 2016 race, that number rose to 36 percent. We could be on the precipice of something unprecedented: the dominance of small-dollar donors.

Remarkably, this transformation is happening without any of the proposed small donor incentives in place. So, what is changing candidates’ behavior? There are two answers: one technological and one cultural.

Technologically speaking, the internet has made fundraising from small donors easier than ever before. Email and social media have made it just as easy to ask one million people for a contribution as it is to ask one. Starting with the Howard Dean campaign in 2004 and then continuing through 2016 with Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump and into this current campaign, presidential candidates have harnessed the scalable nature of the internet with increasing efficiency to raise money directly from millions of small donors. Both Democrats, through ActBlue, and Republicans, with their analogous WinRed, have established dedicated platforms for people to give to the candidates of their choice with just the click of a button. When combined with the visibility and name recognition inherent to a national political campaign, we may be close to peak efficiency when it comes to presidential fundraising.

The efficiency of the internet only explains part of the increase in giving. As I noted, in the 2016 election, small donors only gave 36 percent of political funds and the technology hasn’t changed that much since then. But the culture around giving has changed. Candidates can point to successful small donor totals and convincingly tell the story that the average person pitching in makes a difference. For example, ActBlue, the Democratic small donor vehicle, keeps a running tally on its website of the total dollars raised for candidates. At the time this article was written, that number was over $3.6 billion — big enough so that people can see a real, communal action adding up to something significant. In that light, pitching in $20 towards the candidate of your choice becomes a more rational act.

Hopefully, successful small donor fundraising creates a virtuous cycle. Being supported by regular folks instead of big money has always had political appeal, but it wasn’t a realistic way to fund a campaign. These trends give us hope that once it’s consistently viable to run a campaign funded by small donors, candidates will do so AND use that fact to distinguish themselves, positively, from their opponents. Already, we see candidates touting that they have the smallest average contribution. That is an outcome we could only have dreamed of just a few years ago.

While the rise of the small-dollar donor is real, we can’t declare victory over big money quite yet. Big money may just be biding its time until the Democratic field is smaller, and will then roll in and swamp the small-dollar donors. And, whatever happens in the rest of the 2020 race, big money still has super PACs and other vehicles to give it an out-sized role in the election.

To be clear, the dynamic is very different in a presidential election. The confluence of factors driving the rise of the small-dollar donor in the presidential election probably won’t have the same impact in other races with lower levels of national media coverage and visibility. Beyond greater name recognition, candidates for president have a much larger fundraising pool — the whole country — than candidates for lower offices. Both of these advantages create a scale that makes small donor fundraising a particularly viable tool for a presidential campaign. The same cannot be said for Congressional, state and local elections.

Bottom line: small donors finally are gaining a meaningful voice in our presidential primaries. Political and cultural developments mean that it is NOT always more expedient to rely on big money to fund a presidential campaign. While it is still early in the 2020 campaign, this is a trend worth noting and, for now, celebrating.

Topics

Authors

Joe Ready

Find Out More

TexPIRG fall update

How misinformation on social media has changed news

Small donor public financing victory in Anne Arundel County